The Stranger Study Guide Characters and terms: Meursault Marie Cardona Raymond Sintès Masson Salamano Celeste the narrator’s boss Maman Thomas Perez the caretaker of the home the director of the home the chaplain of the jail the magistrate the prosecutor the little robot woman Algiers Paris Absurdism -- philosophy based on the belief that man exists in an irrational and meaningless universe and in which man’s life has no meaning outside his own existence. (absurd = ridiculously unreasonable, irrational, meaningless) Narrative voice, tone, and diction: • First-person, Meursault, the protagonist, as narrator. (As such, no other character’s thoughts are known except from what can be interpreted by what the character says and does.) • Meursault’s narration is extremely flat in tone, very matter-of-fact. He states mostly what he did and said, and sometimes what he was thinking, but rarely what he felt when he was doing it, or what he felt that caused him to do it. He also relates experiences of pleasure or pain, but these experiences are exclusively caused by external stimuli such as light, temperature, and immersion in water. Rarely does Meursault react emotionally to people. Exceptions to this are his extremely negative feelings toward the mourners during the vigil for Maman (pp. 10-11) and of course when he snaps and attacks the chaplain. • The largely emotionless tone of Meursault’s narration is well-explained in the text and matches his psychology and philosophical outlook. [See the “Meursault on Meursault” quotes below.] • Meursault’s diction (word choice) is mostly simple and direct, in accordance with his straightforward narration and matter-of-fact tone. Even though he has a strong philosophical viewpoint, he doesn’t sound like a philosopher – his vocabulary is not elevated and he makes no references to literature or philosophy. Thus he comes across as an everyman, not an intellectual. He also uses little figurative language, with two exceptions: the final pages of both part 1 and part 2. In his depiction of his shooting the Arab, Meursault’s sudden use of figurative language adds to the sense of his disorientation (he does not sound like himself) (pp. 5759). In the final scene, the use of metaphor in the second-to-last paragraph (pp. 120-22) accentuates what he’s revealing about his beliefs, making his thoughts more forceful and frightening (“the dark wind,” etc.). And in the final paragraph of the novel, his use of metaphor poeticizes his love of life and the sensual world. The Stranger Study Guide 2 of 6 Quotes and Commentary • Camus on Meursault (from his “Preface”): … the hero of my book is condemned because he does not play the game. In this respect he is foreign to the society in which he lives; he wanders on the fringe, in the suburbs of private, solitary, sensual life. Meursault doesn’t play the game. … [H]e refuses to lie. … He says what he is. He refuses to hide his feelings, and immediately society feels threatened. For me, … Meursault is … a poor and naked man enamored of a sun that leaves no shadows.* Far from being bereft of all feeling, he is animated by a passion that is deep because it is stubborn, a passion for the absolute and truth. This truth is still a negative one,** the truth of what we are and what we feel, but without it no conquest of ourselves or of the world will ever be possible. • * “sun that leaves no shadows” = absolute truth. ** the negative truth is the absurdity of existence. Meursault on Meursault: Looking back on it [my life], I wasn’t unhappy. When I was a student, I had lots of ambitions …. But when I had to give up my studies I learned very quickly that none of it really mattered. (p. 41) [On killing the Arab] I knew that I had shattered the harmony of the day, the exceptional silence of a beach where I’d been happy.* Then I fired four more times** at the motionless body … And it was like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness. (p. 59) * Note that he does often express happiness with the sensual pleasures of life. ** What Meursault doesn’t do is analyze or explain his emotions: Why does he shoot again? What is he feeling? We are left to interpret this, just as he have to interpret Burt’s self-defeating actions in “A Serous Talk.” Meursault often states that he doesn’t know why he says or does something, such as when he “snapped” and attacks the chaplain; but he might state that such questions are meaningless, as nothing matters anyway. See the next two quotes. I answered [his defense attorney] that I had pretty much lost the habit of analyzing myself and that it was hard for me to tell him what he wanted The Stranger Study Guide 3 of 6 to know. I probably did love Maman, but that didn’t mean anything. (p. 65) I explained to him, however, that my nature was such that my physical needs often got in the way of my feelings. The day I buried Maman, I was very tired and sleepy, so much so that I wasn’t really aware of what was going on. What I can say for certain is that I would rather Maman hadn’t died. (p. 65) * * * I grabbed him by the collar of his cassock. I was pouring out on him everything that was in my heart, cries of anger and cries of joy. (1) He seemed so certain about everything, didn’t he? And yet none of his certainties was worth one hair of a woman’s head. (2) He wasn’t even sure he was alive, because he was living like a dead man. (3) … But I was sure about me, about everything, surer than he could ever be, sure of my life and sure of the death I had waiting for me. … I had been right, I was still right, I was always right. (4) I had lived my life one way and could just as well have lived it another. I had done this and I hadn’t done that. I hadn’t done this thing but I had done another. And so? … Nothing, nothing mattered, and I knew why. So did he. Throughout the whole absurd life I’d lived, a dark wind had been rising toward me from somewhere deep in my future, … and as it passed, this wind leveled whatever was offered to me at the time … (5) What did other people’s deaths or a mother’s love matter to me; (6) what did his God or the lives people choose or the fate they think they elect matter to me when we’re all elected by the same fate, (7) me and billions of privileged people like him who also called themselves my brothers? (8) Couldn’t he see, couldn’t he see that? Everybody was privileged. There were only privileged people. (9) The others would all be condemned one day. And he would be condemned. too. What would it matter if he were accused of murder and then executed because he didn’t cry at his mother’s funeral?” (10) (pp. 120-21) (1) Note Meursault’s passion, an outburst of both fury and happiness (because he’s convinced in the rightness of his beliefs; that the truth is on his side). (2) The chaplain’s certainties about God and the afterlife are worthless because, Meursault asserts, they are false. No one can know these things for certain, and the uncertainty renders them meaningless. (3) “Living like a dead man” = the chaplain is not really living life to its fullest, enjoying the sensual pleasure that Meursault gets from life. Rather, the chaplain The Stranger Study Guide 4 of 6 ignores the sensual while waiting in solemn expectation for an afterlife that may not exist. (4) Meursault is right about life’s meaninglessness, given the uncertainties of the existences of God – an ultimate judge of men’s actions – and of a pleasurable afterlife that, according to the Church, must be earned. (5) All choices are meaningless and nothing matters in life because nothing will change the outcome – i.e., death (the only certainty). Meursault then depicts death metaphorically as a “dark wind” that “leveled whatever was offered me” – i.e., the knowledge of death destroyed everything for him: his ambition, his long-term feelings for others, etc. All that he is able to enjoy, it seems, are momentary, sensual pleasures that are not lasting, just as life is not lasting. He eschews or denies the deep feelings of serious relationships such as familial love and marriage because their seeming permanence is an illusion. (6) The knowledge of the inevitability of death makes the normal sadness people feel about the passing of a loved one meaningless, because everybody dies. “A mother’s love” – i.e., a deep, lasting love – is meaningless because nothing lasts, and because that love is still not powerful enough to prevent Meursault’s death, so what good is it really? Meursault’s death preoccupation makes him profoundly self-centered, as “life has no meaning outside of his [Meursault’s own] existence” (quoting the definition of Absurdism, above). (7) People “choose” their lives, but they only think they have control over (“elect”) their fate. The truth is that everyone has the same fate – i.e., death. (8) Again, Meursault’s tone suggests that he resents being called a “brother,” just as he resented the priest at Maman’s funeral and the chaplain in the jail’s calling him “my son” and the chaplain’s wanting to be called “Father.” This is an indication of Meursault’s deep feelings of isolation, as others do not share his views. His beliefs alienate him from society. (9) Life is a privilege, just as it is. No afterlife is necessary for Meursault to appreciate it. (10) Since we’re all going to die, and since we can’t know if our morality is being judged, when and how you die and issues such as sin and reputation are meaningless. * * * Sounds of the countryside were drifting in. Smells of night, earth, and salt air were cooling my temples. The wondrous peace of that sleeping summer flowed through me like a tide. (1) Then, in the dark hour before dawn, sirens blasted. They were announcing departures for a world that now and forever meant nothing to me. (2) For the first time The Stranger Study Guide 5 of 6 in a long time I thought of Maman. I felt as if I understood why at the end of her life she had taken a “fiance,” why she had played at beginning again. (3) … So close to death, Maman must have felt free then and ready to live it all again. (4) Nobody, nobody had the right to cry over her. (5) And I felt ready to live it all again too. As if that blind rage had washed me clean, rid me of hope; (6) for the first time, in that night alive with signs and stars, I opened myself up to the gentle indifference of the world. (7) Finding it so much like myself – so like a brother, really (8) – I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again. (9) For everything to be consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet me with cries of hate.” (10) (pp. 122-23) (1) These sentences again emphasize the sensual pleasure Meursault obtains from being alive. His poetic use of metaphor emphasizes the pleasure he’s experiencing. (2) The sirens are apparently from the jail, announcing executions. In saying that the dying people are “departing for a world that … meant nothing to me,” Meursault is asserting that, even if in fact an afterlife exists, he refuses to value it because of the uncertainty he has of it. All he values is this life, of which he can be certain. (3) The key word here is “played.” Maman is able to “play” at beginning again, because, now that death is so near, she can relax about it and happily ignore it. Meursault has been tortured by consciousness of death, and thus unable to “play” and enjoy more than ephemeral pleasures. (4) Maman is freed by her proximity to death; it becomes more enjoyable – suddenly worth living, which is something that Meursault has not felt in his life. Life felt burdensome to him, poisoned by the “dark wind.” (5) This is the hardest line to decipher. I think Meursault is saying that “nobody had a right to cry over [Maman]” because she was happy; and perhaps also that death is a release from the burden of the consciousness of death. He also seems offended, however, that others should cry when he, her closest relative, knows better than to cry: they had “no right,” because they were wrong to do it; it’s presumptuous. (6) The “blind rage” he refers to was directed at the chaplain. Now that he has finally vocalized the truth about death that has haunted his whole life, he feels cleansed. He also says here that it “rid me of hope,” telling us that, despite everything Meursault has stated about his consciousness of death’s inevitability, he nevertheless clung to a futile hope that he could somehow be spared. (7) The “signs and stars” in the night sky are perhaps part of the world’s “gentleness,” as they are beautiful and poetic, creating for humanity the illusion of hope. Meursault asserts, however, that the world is ultimately “indifferent” to the fates, problems, and behavior of humans: No one is watching out for you. The only thing truly fated is The Stranger Study Guide 6 of 6 death. Meanwhile, Meursault’s saying that he “opened … up” emphasizes that his upset over the knowledge of death has shut him off from feelings. He has kept himself closed up in a shell, isolated from the world as well as other people. (8) The world’s ultimate “indifference” to humans echoes the indifference that Meursault has demonstrated to everyone around him throughout the novel. Thus, alienated from society and insulted when the priest and chaplain call him “son,” Meursault feels a kinship with the natural world, in which he takes such sensual pleasure, and is willing to embrace it as being “like a brother.” (9) Meursault acknowledges the pleasure he has felt in living, despite the burden of the consciousness of death. And now, close to death and with the absolute certainty that there is no hope of reprieve from his death sentence (with which everyone lives), he, like Maman at the end of her life, feels released from his burden – happy and free. (10) This last sentence of the novel emphasizes both Meursault’s terrible loneliness and alienation from society.

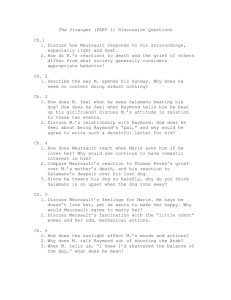

![Dialectical_Journal_The_Stranger_Part_1_Chapter_1[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009474360_1-13e4833f16103af98d9991d7a02cbbc4-300x300.png)