17766-Article Text-25028-1-10-20140825

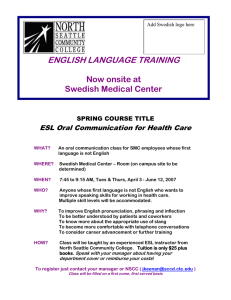

advertisement