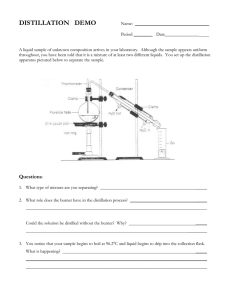

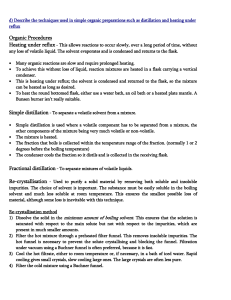

235Manual

advertisement