De Geest, B.G. Soft Matter 2009

advertisement

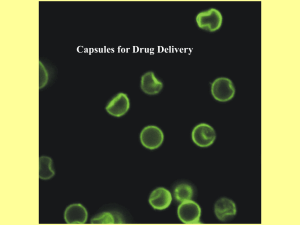

Soft Matter www.softmatter.org Volume 5 | Number 2 | 21 January 2009 | Pages 253–480 Introducing Professor Darrin Pochan Associate Editor for North America Submit your work to Soft Matter Professor Pochan will be delighted to receive submissions from North America on any aspects of soft matter research. Submissions to Soft Matter are welcomed via ReSourCe, our homepage for authors and referees (www.rsc.org/resource). For any enquiries, please contact Professor Pochan at softmatter@udel.edu. ISSN 1744-683X REVIEW Bruno G. De Geest et al. Polyelectrolyte microcapsules for biomedical applications HIGHLIGHT Lin Feng, Lei Jiang et al. Smart responsive surfaces switching reversibly between super-hydrophobicity and superhydrophilicity “I will strive for fast turnaround of submitted manuscripts with two or three rigorous and appropriate reviews. My goal is an expedient review process and fast turn-around of excellent work.” www.softmatter.org Registered Charity Number 207890 110802 Darrin Pochan is Associate Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at University of Delaware. His research interests centre around the specific rules and general paradigms underlying molecular design and self-assembly of unique polymeric, peptidic, and organic–inorganic hybrid materials. REVIEW www.rsc.org/softmatter | Soft Matter Polyelectrolyte microcapsules for biomedical applications Bruno G. De Geest,*ab Stefaan De Koker,†b Gleb B. Sukhorukov,c Oliver Kreft,d Wolfgang J. Parak,e Andrei G. Skirtach,d Jo Demeester,b Stefaan C. De Smedtb and Wim E. Henninka Received 3rd June 2008, Accepted 18th August 2008 First published as an Advance Article on the web 16th October 2008 DOI: 10.1039/b808262f In this paper we review the recent contributions of polyelectrolyte microcapsules in the biomedical field, comprising in vitro and in vivo drug delivery as well as their applications as biosensors. Introduction Polyelectrolyte microcapsules,1–5 fabricated by layer-by-layer (LbL) coating6 of a sacrificial template followed by the decomposition of this template, have gathered increased interest as novel entities for drug delivery and diagnostic purposes.3,5,7–10 Briefly explained, the LbL technique is based on the alternating adsorption of charged species onto an oppositely charged substrate, using electrostatic interactions as the driving force. The main advantage of the LbL technique is the ease of manipulation and the unmet degree of multifunctionality,11 allowing one to tailor the surface with different kinds of functional groups,12–14 lipids,15–19 nanoparticles20–22 etc. Polyelectrolyte capsules are made by coating a spherical substrate with alternating polyelectrolyte layers of opposite charge.3 Once a certain thickness of the multilayer coating is achieved, the spherical substrate is dissolved and the obtained capsules are thoroughly washed to remove the dissolved decomposed products of the sacrificial template. Molecules can be entrapped into polyelectrolyte capsules after fabrication of the a Department of Pharmaceutics, Utrecht University, 3584 CA, Utrecht, The Netherlands. E-mail: br.degeest@ugent.be; Fax: +32 9 264 81 89; Tel: +32 9 264 80 74 b Laboratory of General Biochemistry and Physical Pharmacy, Ghent University, Belgium c IRC, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom d Max Planck Institute for Colloids and Surfaces, Golm, Germany e Philipps University Marburg, Department of Physics, Marburg, Germany † Author who contributed as equally as the first author. Bruno De Geest Bruno De Geest graduated as a chemical engineer in 2003 from Ghent University in Belgium, where he obtained his PhD in 2006. Following two years of post doctoral research at the University of Utrecht in The Netherlands he obtained a post doctoral fellowship at the Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Technology at Ghent University. His main interest are the overlap between chemistry, materials science, medicine and biology. 282 | Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 capsules by temporarily switching capsule permeability23–26 or during the generation of the capsules by incorporating them into the porous substrate that serves as a template for LbL coating.27,28 When the molecular weight of the molecules is sufficiently high or when they remain entrapped by electrostatic interaction, they remain entrapped while the low molecular weight degradation products (often ions as is the case for carbonate or silica based templates) of the sacrificial template can diffuse through the capsule’s wall.29 Fig. 1 schematically represents the fabrication of hollow polyelectrolyte microcapsules in the case where calcium carbonate is used as a sacrificial template. Intracellular delivery Introduced in 1998 as a physicochemical oddity, these capsules have evolved towards delivery vehicles for different types of Fig. 1 A schematic representation of the synthesis of hollow polyelectrolyte microcapsules using calcium carbonate (CaCO3) as a sacrificial core template. Macromolecules are co-precipitated with CaCO3 by mixing them with calcium chloride and sodium carbonate (A). These macromolecule loaded particles are coated with several layers of polyelectrolytes of alternate charge (B) followed by the dissolution of calcium carbonate core template in an EDTA solution (C). Reprinted with permission from De Koker et al.30 Stefaan De Koker Stefaan De Koker graduated as a bio-engineer from Ghent University in 2001. He started his PhD at the VIB, at the Department for Molecular Biomedical Research. Currently, he is finishing his PhD at the Department of Pharmaceutics at Ghent University. The main focus of his work is evaluating biodegradable polyelectrolyte microcapsules as novel antigen delivery tools in the field of vaccination. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 form a pore-like structure with an internal diameter of 10 nm. Only molecules smaller than 40 kDa can diffuse freely through these pores. For larger molecules, transport to the nucleus is an active process dependent on the presence of nuclear localization signal peptides that interact with specific transporter molecules. Due to technical limitations the design of polyelectrolyte capsules that are small enough to cross the nuclear membrane appears highly doubtful. On the other hand, it could be a major challenge to equip polyelectrolyte capsules with virus-like properties allowing the capsules to enhance the transport of their payload through the nuclear membrane into the nucleus of the cell. Fig. 2 A schematic representation of a mammalian cell and the different intracellular regions which can be aimed to deliver therapeutic molecules: (1) the endosomal compartment, (2) the cytosol and (3) the nucleus. These regions are each shielded by their respective membranes. molecules that serve as therapeutic agents or allow the conducting of diagnostic assays on the capsules’ surfaces31–33 or within their micron sized interiors.34–38 In this review we give an overview of the recent progress that has been made in the development of polyelectrolyte capsules for intracellular purposes, comprising both therapeutic as well as biosensor applications. As it is schematically shown in Fig. 2 there are roughly three zones in a living cell that can be targeted by microcapsules for delivering therapeutics: (1) the endosomal compartment, (2) the cytosol and (3) the nucleus. The endolysosomal compartment of antigen presenting cells (such as dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells) constitutes a highly interesting target for the delivery of antigens (i.e. for vaccination purposes) that are subsequently cleaved into peptide fragments and presented on the cell surface in combination with MHCII class molecules (MHC, major histocompatibility complex), resulting in activation of CD4 + T-helper cells. Besides the endosomes, the cell cytosol can also be a very interesting target for antigen delivery. Cytosolic antigens are cleaved by the proteasome, transported to the ER and eventually presented in combination with MHCI to CD8 + cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). To date, only a few antigen delivery systems are able to initiate CTL responses, which are crucial to kill virally infected cells and tumor cells. In addition, the cytosol can be a target for drug molecules interfering with all kinds of intracellular process, such as e.g. siRNA which can suppress the production of specific proteins.39–42 The nucleus is the target for drugs aiming to change the genetic code of the cell, e.g. to introduce new genes or to repair gene defects.42–44 To reach each of these sites a specific membrane, each with its specific properties, has to be crossed. After being phagocytosed, particles with diameters of up to 10 mm will end up in endosomal/lysosomal/phagosomal compartments.45 Several strategies have been developed to help particles escape from the endosomal compartment to the cytosol.46–55 In theory such strategies could also be used to functionalize the surface of polyelectrolyte capsules. However, this has not yet been reported in literature and the question regarding whether polyelectrolyte capsules can escape from the endosomal compartment has not yet been addressed thoroughly. Transport of macromolecules to the nucleus is regulated by so-called nuclear pore complexes.44,56–58 These complexes consist of several hundreds of nucleoporins that This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 Uptake, toxicity and biodegradability Intracellular delivery implies ubiquitously that the capsules should be able to cross the cellular membrane and deliver their content in the cytosol of the cells or at least reach the endosomal compartment. The interactions between capsules and living cells have been studied by several groups addressing different aspects59 such as uptake kinetics and mechanisms, toxicity, intracellular degradation as well as strategies to enhance or block the capsule uptake. Sukhorukov et al. were the first to demonstrate cellular uptake of polyelectrolyte capsules.10 They showed that breast cancer cells could internalize up to thirty 5 mm sized capsules, composed of PSS–PAH polyelectrolytes, per cell, only leading to a small capsule deformation due to mechanical stress exerted by the cells. In subsequent studies Parak et al. addressed the toxicity of such capsules. They demonstrated that capsules alone do not exhibit acute cytotoxic damage on cell cultures, but that rather nanoparticles with which capsules are functionalized are potentially cytotoxic.60 This is in particular true for colloidal quantum dots which have been suggested as fluorescence labels in the wall of capsules for the purpose of visualization.61 For this reason upon functionalization of capsules with colloidal nanoparticles the cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles always has to be considered, as embedding the nanoparticles in the polymer walls of the capsules does not reduce their cytotoxicity. For therapeutic purposes there is a clear need for the capsules to be biodegradable. During the past decade several bio-polyelectrolytes, such as polysaccharides, polypeptides or polynucleotides, which are potentially biodegradable have been used for the fabrication of capsules. Degradable multilayers on planar surfaces have been reported by Picart et al., both in vitro and in vivo, using the above mentioned bio-polyelectrolytes.62 Degradation was based on enzymatic action following cellular invasion in the multilayers. A second class of degradable multilayers on planar substrates was introduced by Lynn and co-workers using poly-b-aminoesters.63–70 These polymers are polycations containing biodegradable ester bonds in their backbone, leading to the erosion of the multilayers and the release of potentially therapeutic polyanions. Recently the same group also reported on so-called charge-shifting polyelectrolytes which upon hydrolysis undergo a shift from polyanionic to polycationic or visa versa. This approach allowed the release of both anionic and cationic species incorporated in between hydrolysable layers.69,71,72 Similarly, polyelectrolyte capsules that can be degraded through ester hydrolysis or enzymatic action were obtained by De Geest et al. using poly(HPMA–DMAE) as a degradable polycation and dextran sulfate/poly-L-arginine as bio-polyelectrolytes Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 | 283 Fig. 4 A schematic representation of the encapsulation of drug molecules (green dots) and pronase (red Pac-Man shapes) within calcium carbonate microparticles (A–B) followed by LbL coating of the microparticles with polypeptide layers of opposite charge (B). When the enzyme is liberated into the empty void of the capsules by dissolving the calcium carbonate (C), it starts to hydrolyse the peptide bonds of the multilayers, releasing the encapsulated drug molecules. Reprinted with permission from Borodina et al.78 Fig. 3 The molecular structure of the degradable polyelectrolytes used by De Geest et al. for the synthesis of intracellular degradable capsules.73 Confocal microscopy images of intracellularly degraded (A) [poly(HPMA– DMAE)–poly(styrene sulfonate)]4 capsules and (B) (dextran sulfate–poly73 L-arginine)4 capsules. Reprinted with permission from De Geest et al. (Fig. 3A)73 Poly(HPMA–DMAE) is a so-called charge-shifting polymer,69,71,74 meaning that it shifts from a cationic charge (due to the tertiary amine groups) to a neutral charge upon hydrolytic cleavage of the carbonate ester which connects the cationic amine moiety to the polymer backbone. Incubation of poly(HPMA– DMAE) containing polyelectrolyte microcapsules in a physiological buffer at 37 C results in the hydrolysis of the ester bonds, causing the decomposition of the microcapsules. Degradation of dextran-sulfate–poly-L-arginine microcapsules on the other hand, requires proteolytic cleavage, as was demonstrated by their fast disappearance when incubated in a pronase solution (i.e. a mixture of proteases able to cleave virtually every peptide bond). Both these capsules were readily taken up by VERO cells and degraded intracellularly. Sixty hours after incubation, no intact capsules could be observed inside the cells any more (Fig. 3A and B) while capsules based on non-degradable polyelectrolytes remained intact.73 When transferred into an in vivo situation, the poly(HPMA– DMAE) based capsules will degrade under all physiological conditions and will therefore differ little from traditional degradable microparticles. However, in healthy tissue the enzymatically degradable capsules will likely remain intact in the extracellular space and will become degraded solely after uptake by phagocytosing cells. Thereby, these capsules can potentially be used as a delivery system to specifically target bioactive (macro)molecules towards the intracellular compartment of phagocytosing cells. Several other groups have further explored the concept of capsule degradation. Itoch et al.76 and Wang et al.75 demonstrated that capsules based on respectively chitosan and 284 | Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 hyaluronic acid could be degraded by their specific digesting enzymes such as chitinase and hyaluronidase.75–77 Lee et al.77 investigated the pepsin mediated degradation of capsules constituted of alginate and chitosan. Degradation of these capsules however requires the presence of these specific enzymes in close proximity of the capsules. As the expression of these enzymes is highly restricted in vivo (e.g. pepsin is only present in the gastro-intestinal track), this could seriously limit their in vivo degradation. An elegant approach to stimulate capsule degradation was recently reported by Borodina et al., who encapsulated shell digesting enzymes inside the confined volume of the capsules themselves.78 Fig. 4 shows a schematic representation of the proposed concept. The bioactive compound (being DNA) was co-encapsulated with pronase (being the digesting enzymes) by co-precipitation with calcium carbonate, resulting in calcium carbonate microparticles loaded with both DNA and pronase in their porous matrix. Subsequently these microparticles were LbL coated with multilayers of poly-L-aspartic acid and poly-L-arginine. These polyelectrolytes are both polypeptides and should thus be susceptible to enzymatic hydrolysis by pronase. Indeed, it was shown that upon incubation of the microcapsules under physiological conditions the microcapsules spontaneously decomposed and subsequently released the encapsulated DNA. It was further observed that the release rate of DNA was strongly dependent on the amount of encapsulated pronase that was initially loaded inside the microcapsules. Moreover, as pronase activity is temperature dependent no activity was observed at 4 C, allowing the temperature controlled release of DNA. Relatively few studies have addressed the in vivo behaviour of polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies. Picart et al. have shown that polyelectrolyte multilayers can be digested by enzymatic action when placed in the peritoneal62 and oral environments.79 The biocompatibility and in vivo fate of dextran sulfate–polyL-arginine polyelectrolyte capsules after subcutaneous injection were recently assessed by De Koker et al.30 Injection of the microcapsules resulted in a typical foreign body response, characterized by a fast recruitment of inflammatory cells to the injection site (Fig. 5). The microcapsule mass behaved similarly to a porous implant, with cellular infiltration starting at the periphery and gradually proceeding towards the centre. Within one week, 5–10 layers of fibroblasts surrounded the injected volume. As time progressed, mononuclear phagocytes internalizing particles increasingly replaced polymorphonuclear cells. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 Fig. 5 Hematoxylin and eosin stainings of skin tissue sections at different time intervals after subcutaneous injection of (dextran-sulfate–polyL-arginine)4 polyelectrolyte capsules. The insets show an enlarged picture of a selected area (R1). Microcapsules appear as discs. One day after injection the microcapsules have retained their shape and are infiltrated by predominantely polymorphonuclear cells. One week later the injection mass is surrounded by fibroblasts while cellular infiltration gradually proceeds to the centre. After one month microcapsule remnants are visible inside mononuclear phagocytes. Reprinted with permission from De Koker et al.30 Importantly, although injection resulted in a mild to moderate inflammatory response, no severe side effects such as tissue necrosis were observed at any time, establishing the feasibility of using polyelectrolyte capsules for in vivo applications. To assess the in vivo uptake and degradation of the dextransulfate–poly-L-arginine polyelectrolyte capsules, RITC-labeled (RITC, rhodamine isothiocyanate) poly-L-arginine was incorporated into the capsules, tissue sections were prepared and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 6). One day after injection and eight days after injection few cells had infiltrated the microsphere mass. The microcapsules clearly had retained their spherical shape and appeared scattered between the cells. No deformed capsules could be seen outside the cells. Sixteen days after injection many capsules had been phagocytosed and lost their spherical shape. One month after injection microcapsules were visible as debris inside the cells. At none of the time intervals assessed deformed particles or particle debris could be observed outside the cells, indicating that particle degradation exclusively occurred after particle uptake (Fig. 6). Different advantages can be envisaged for delivery systems that release their content after cellular uptake. First, if they contain a drug or toxic compound, they can be used to selectively treat or kill cells that phagocytose the particles, while leaving other cells unharmed. Possible strategies for targeting the capsules towards specific cell types like cancer cells will be discussed later. Second, encapsulation of antigen into microparticles has been shown to enhance immune responses by basically two mechanisms: (1) protecting antigens from fast degradation and clearance (2) enhancing the uptake and presentation of the antigen by professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) both via the MHCI and MHCII routes. As biodegradable polyelectrolyte capsules are readily taken up by dendritic cells in vitro30 and appear quite resistant to extracellular degradation, they might be excellent tools for the delivery of antigens to APCs, creating an intracellular depot of the antigen. The real potential of these microcapsules as vaccine adjuvants should be further evaluated using polyelectrolyte microcapsule encapsualted antigens. As an alternative to enzyme- or hydrolysis-sensitive capsules, one could also be interested in using the change in physiological environment when crossing the cellular membrane to trigger capsule disassembly. The two most outspoken changes a particle encounters upon cellular uptake are (1) a decrease in pH from 7.4 in the extracellular space to approximately 5.2–5.4 in the endosomal compartment and (2) the transition from an oxidative to a strong reductive environment. Theoretically, it should be possible to synthesize pH-sensitive polyelectrolyte capsules that decompose upon the decrease in pH which takes place in the endosomal compartment. To obtain this goal, weak polyelectrolytes with a pKa between 5.2 and 7.4 are needed. Upon lysosomal acidification such polyelectrolytes would lose their negative charges resulting in capsule disassembly due to a loss of electrostatic interactions. However, upon complexation with an oppositely charged polyelectrolyte a substantial shift in apparent pKa occurs, rendering the capsules more stable over a wider pH range than predicted by the pKa values of the individual polyelectrolytes components.80 The fundamental basics of this phenomenon were investigated by Petrov et al.81 and nicely illustrated by Mauser et al.82 showing that polyelectrolyte capsules based on poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH, pKa ¼ 8.5) and poly(methacrylic acid) (PMA, pKa ¼ 4.5) are stable in the pH range 2 to 11. In order to decompose or at least swell and release their content upon lysosomal acidification polyanions and polycations should be designed so that their apparent pKa in a complexed state is situated between 5.2 and 7.4. The second major physicochemical change encountered when crossing the cellular membrane is a transition from an oxidative to a reductive environment, both in the endosome and the cytosol. Disulfide bonds have the interesting property of being cleavable under reductive conditions. Caruso et al. have exploited this property to stabilize hydrogen bonded capsules based on poly(vinyl pyrolidone) and poly(methacrylic acid) (PMA) under oxidative conditions by modifying the PMA with cysteamine moieties.83–86 When the capsules were transferred to a reductive environment, the hydrogen bonded multilayers were no longer stable as the disulfide bonds were cleaved, resulting in the Fig. 6 Confocal microscopy images of tissue sections taken at several time points after subcutaneous injection of (dextran sulfate–poly-L-arginine)4 capsules. The capsule’s wall was stained with rhodamine (red fluorescence) and the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). The insets in the top right corners show the cellular uptake and degradation at a higher magnification. Reprinted with permission from De Koker et al.30 This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 | 285 disassembly of the capsules. This approach offers an appealing opportunity to trigger capsule disassembly by a physiologically relevant stimulus, as the authors further showed that intracellular gluthathione concentrations indeed cause capsule disassembly. However, since these experiments were performed in a test tube setting it still remains to be demonstrated that capsules also disintegrate after cellular uptake. Enhancing/blocking cellular uptake One of the major advantages of the LbL technology is without doubt its multifunctionality, allowing one to tailor the capsules’ surfaces with a virtually unlimited range of components. This unique feature also introduces the possibility of modulating capsule uptake or targeting the capsules towards certain cell populations. In this regard, several groups tried to impede cellular uptake of the capsules by functionalizing their surface with an outer layer of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). PEG is well known for its so-called stealth properties, blocking protein adsorption to surfaces, a feature that has been successfully applied to reduce recognition by macrophages. Using streptavidin as model protein Heuberger et al. showed that there was almost no adhesion to the capsule surface through non-specific protein adsorption in the case where the capsules were functionalized with an outermost layer of poly-L-lysine-PEG.87 However, in the case where the PEG was end-functionalized with biotin a strong binding affinity of streptavidin to the capsules was observed. These findings demonstrate the feasibility of functionalizing the capsules’ surfaces with ligands that could allow a more specific cellular targeting of the microcapsules. Although PEGylation of the polyelectrolyte microcapsules largely blocks protein adsorption to the capsules’ surfaces,87 the effect of PEGylation on cellular uptake was rather moderate (Fig. 7A–B), indicating that other factors also significantly affect polyelectrolyte microcapsule uptake.88 Targeting the microcapsules towards selected tissues/cells, would enable the selected delivery of their content to these tissues. Clearly, achieving this can offer tremendous benefits, the most obvious presumably in the field of cancer therapy. Selective delivery of cytostatic agents/drugs to tumor cells not only may drastically enhance therapy efficiency, but also significantly decrease deleterious side effects. Several groups have tried to accomplish this goal, using totally different approaches. The Sukhorukov group incorporated magnetic nanoparticles in the capsules’ shells (Fig. 7D). By applying a magnetic field gradient, it was feasible to direct capsules to a region of interest. Due to the local accumulation of capsules, cells in this area were found to have taken up significantly more capsules than distant cells.89 An alternative strategy was explored by the Caruso group,90,91 who functionalized the capsules’ surfaces with a humanized A33 monoclonal antibody (huA33; Fig. 7C). This antibody binds the human A33 antigen, a transmembrane glycoprotein that is expressed by 95% of all human colorectal tumor cells as well as on the basolateral surfaces of intestinal epithelial cells. Upon binding of the huA33 to the A33 antigen, the cellular internalization mechanism is activated providing a mechanism for particles to be taken up. As shown in Fig. 7C, polyelectrolyte capsules coated with huA33 are readily internalized by colorectal cells expressing the A33 antigen, while colorectal tumor cells that do not express the A33 antigen fail to take up the particles. Both of the above mentioned strategies open the way for targeting polyelectrolyte capsules towards specific tissues in the body. However, to be applicable in clinical practice several additional hurdles have to be overcome. First of all, to reach a specific tissue intraveneous administration is often required. Therefore, the size of the capsules should be limited to around 200–500 nm as they would be prone to clogging in the smallest blood capillaries. Secondly, due to their polyionic nature, they are very susceptible to protein adsorption, leading to clogging in the blood capillaries as well as opsonisation and scavenging by Fig. 7 Schematic structure of the ligands used to block/promote cellular uptake of polyelectrolyte capsules, being PLL–PEG, PGA–PEG, antibodies and magnetic nanoparticles. Confocal microscopy images of (A) capsules being internalized by cells, (B) PLL–PEG coated capsules being prevented from cellular internalization and huA33 mAb functionalized capsules being internalized by LIM1215 colorectal cells. In images (A–C) the capsules were stained with a green fluorescent dye, in (C) the cellular membrane was stained with a red fluorescent mouse mAb to show the EGF receptor (mAb 528). In image (D) the capsules were stained with red fluorescent quantum dots. Reprinted with permission from Wattendorf et al.,88 Cortez et al.91 and Zebli et al.89 286 | Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 macrophages. Hence, improved stealth strategies need to be developed in order to allow the specific targeting of microcapsules either via magnetic guidance or by antibody mediated recognition. Once this has been addressed, the challenge will be to demonstrate that polyelectrolyte capsules have substantial benefits compared to liposomes, and other conventional particles from the drug delivery scene. Triggered release from polyelectrolyte capsules After reaching their target site, microcapsules need to release their encapsulated contents.8 Among a variety of release mechanisms, those with remote functionalities, for example by external forces such as light,92–98 ultrasound,99–101 hydrolysis102–106 or magnetism107 represent interesting strategies for controlled drug release after administration, by opening the capsules after they have reached their target tissue. Recently, several research groups have reported on the light triggered activation of polyelectrolyte capsules inside living cells. Skirtach et al. showed that polyelectrolyte capsules functionalized with gold nanoparticles could be opened remotely inside living cells by irradiation with laser light.108 When operating in a tissue environment, it is desirable to minimize the side effects of the applied irradiation. Thereby, the near-infrared ‘‘biologically transparent’’ window appears particularly attractive. Near-infrared absorption could be induced either by aggregates of nanoparticles109,110 or nanorods.111 The latter are particularly attractive, because they allow wavelength tunability of remote release.112 Shell-in-shell microcapsules could be activated for conducting bio-reactions in confined volumes if the inner shell is functionalized with nanoparticles.22 Various nanoparticles, including gold,92–97 and silver113,114 are suitable for the remote release of encapsulated materials. Alternatively, organic moieties could be used as sensors for inducing release. In this regard, remote activation by an IR-dye was shown.94 Another concept of light activated polyelectrolyte capsules was introduced by Wang et al. using capsules containing hypocrellin B (HB), a photosensitizer.115 HB is used in so-called photodynamic therapy for treatment of diseases such as cancer, viral infections etc. In absence of light HB is not cytotoxic, however after exposure to light irradiation singlet oxygen (1O2) is generated which is cytotoxic and induces cell death. As HB is not water-soluble it should be contained in a pharmaceutical formulation allowing it to enter living cells. Therefore HB was loaded into the capsules by non-specific interactions applying a solvent exchange step using ethanol as the solvent for the HB. When the HB loaded capsules were incubated with living cells they were taken up by these cells. It was shown that neither empty capsules nor HB loaded capsules were cytotoxic for the cells. However, upon irradiation with 488 nm light, a 70% drop in cell viability was observed in the HB microcapsules treated cells. Although this concept surely holds potential to be applied in an in vivo setting, it remains a challenge to demonstrate the benefit of using polyelectrolyte capsules instead of more conventional delivery forms for hydrophobic drugs such as e.g. PLGA nano- or microparticles, liposomes or micelles. Delivery of chemotherapeutic molecules Several classes of therapeutic molecules have an intracellular target. Amongst them are low molecular weight compounds such This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 Fig. 8 The fluorescence intensity averaged from inside the circles shown in the inset figure as a function of incubation time. 1 and 2 refer to the capsule interiors, 3 refers to the bulk. Rhodamine 6G was used as a low molecular weight model drug and (PSS–PAH)5 capsules templated on 8.7 mm sized melamine formaldehyde particles were used. Reprinted with permission from Liu et al.119 as chemotherapeutics and high molecular weight compounds such as proteins and oligo/polynucleotides like e.g. those in ref. 42 and 116. Several groups have addressed the encapsulation of the chemotherapeutics doxorubicin and daunorubicin in polyelectrolyte microcapsules. It has been reported that species with a molecular weight lower than 5 kDa can freely diffuse in and out of the polyelectrolyte microcapsules.29 Therefore, an electrostatic loading mechanism is often applied. This technique implies that the interior of the capsules is filled with a compound oppositely charged to the compound one desires to encapsulate. Following incubtion, the low molecular weight compound accumulates inside the polyelectrolyte capsules through electrostatic interaction. This principle has been introduced by Sukhorukov et al. for the controlled precipitation of dyes in hollow polyelectrolyte capsules.25 Khopade and Caruso117 and Tao et al.118 used electrostatic interaction between the cationic doxorubicin and the polyanionic alginate as the driving force for doxorubicin encapsulation in biocompatible capsules. The process of charge driven loading is shown in Fig. 8 taken from Liu et al., and illustrates the accumulation of the positively charged model drug rhodamine 6G inside (PSS–PAH)5 capsules through electrostatic interaction with the anionic PSS–melamine complex.119 After having accumulated inside the capsules, the low molecular weight drug molecules can be partially released due to a concentration gradient between the capsule interior and the bulk solution. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that doxorubicin loaded capsules could kill in vitro cultured HL-60 human leukemia cells, exhibiting slower pharmacokinetics compared to the freely soluble drug. This is an interesting observation as it might decrease the dose-limiting toxicity. It should however be noted that the authors of the above mentioned papers have not yet investigated whether the capsules released their content following intracellular internalization or whether the drug was released in the medium surrounding the cells. Recently two Chinese groups performed in vivo studies with such chemotherapeutic loaded capsules.120,121 Both groups used CaCO3 microparticles doped with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) as a sacrificial template for LbL coating with 5 bilayers of the biopolymers chitosan/alginate. Through electrostatic interaction with the anionic CMC doxorubicin and daunorubicin Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 | 287 weeks, the tumors were dissected and their size was compared to either untreated or non-encapsulated daunorubicin treated tumors. As shown in Fig. 10 the mice treated with encapsulated daunorubicin showed the lowest increase in tumor size. Polyelectrolyte capsules as biosensors Fig. 9 Dual channel CLSM (confocal laser scanning microscopy) images to show the apoptotic BEL-7402 cells induced by the encapsulated DNR (daunorubicin). (a) Excitation at 488 nm, (b) excitation at 543 nm, (c) transmission mode, and (d) is an overlapping image of (a) and (b). The cells are stained by AO (acridine orange). Reprinted with permission from Han et al.121 could be incorporated inside the capsules. Fig. 9 shows the effect of daunorubicin loaded capsules upon incubation with cultured BEL-7402 cancer cells. Acridine orange was used to stain the chromatin, which is present only in the nucleus in the case of healthy living cells. The dispersion of the red fluorescent signal throughout the whole cell indicates that the nuclear membrane of the cells had disappeared, meaning that cell apoptosis is induced by the encapsulated daunorubicin. In a next step BEL-7402 cells were implanted in nude BALBc mice and the daunorubicin capsules were directly injected into the tumor tissue. After 4 Fig. 10 Overview of the BEL-7402 BALB/c/nu tumors. From top to bottom: control (without treatment), treated by free DNR and treated by encapsulated DNR. Encapsulated and free DNR with a dosage of 1 mg kg1 (against the weight of mice) was injected into the tumors once a week for 3 weeks (qw3). Reprinted with permission from Zhao et al.120 288 | Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 Since both the capsules’ interiors and their surfaces can be rendered sensitive to specific physicochemical stimuli, the capsules might be applied as biosensors for diverse applications. Theoretically, polyelectrolyte capsules composed of one or two weak polyelectrolytes could be directly used as pH sensors. Such capsules lower their charge density when the pH of the surrounding medium passes the pKa of one or both polyelectrolytes. This decreases the electrostatic interaction between the polyelectrolyte layers, resulting in swelling and eventually decomposition of the capsules. However, due to differences between the pKa of the polymers in solution and their apparent pKa values after complexation, polyelectrolyte capsules retain their structural integrity over a broad pH range, even when composed of weak polyelectrolytes, impeding the measurement of swelling as a reliable pH sensor.80 An attractive alternative for overcoming this problem has recently been proposed by Kreft et al. by using SNARF-dextran loaded polyelectrolyte microcapsules.37 SNARF is a pH-sensitive dye that changes its excitation and emission spectra as a function of the pH of the surrounding medium. At high pH (i.e. pH 9) red fluorescence is emitted, whereas at low pH (i.e. pH 4) green fluorescence is emitted. In this way the incorporation of capsules by cells could be visualized. Whereas SNARF loaded capsules in the slightly alkaline cell medium were red fluorescent, the capsules became green fluorescent when incorporated by cells due to the acidic environment in endosomal/lysosomal/phagosomal compartments (Fig. 11). Such pH-sensitive capsules can be used for highthroughput-analysis of capsules by flow cytometry.122 Though this first demonstration was limited to the detection of protons the same principle may be applied also for other ions. This might be in particular interesting for multiplexed detection of several ions in parallel. Capsules could be loaded with different ionsensitive fluorophores in their cavity. Each capsule can then be labeled with a fluorescence barcode in its wall. In this way, the capsules’ wall fluorescence indicates the type of ion being measured, while its inner fluorescence is related to the ion’s concentration. Although such an approach will be primarily applicable for measuring ion concentrations in solution, it might also be useful to measure intracellular ion concentration, especially of ions such as Ca2+ or K+, which exerts crucial functions in cell signaling. As cells can take up several capsules this would allow the concentration of several ions to be measured in parallel. However, for this purpose investigation of whether the capsules can escape the endosomes and reach the cytosol will also be required as this is a particularly interesting region to monitor ion fluctuations. Another promising diagnostic application of polyelectrolyte capsules is being developed by the McShane group for the detection of glucose. Their ultimate goal is to developed a so-called ‘‘smart tattoo’’ implanted in the skin which allows the monitoring of the glucose level by remote interrogation using visible or near-infrared excitation light. For this purpose, This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 Fig. 11 SNARF loaded capsules change from red to green fluorescence upon internalization by MDA-MB435S breast cancer cells. (A) SNARFfluorescence after adding the capsules to the cell culture and 30 min equilibration. Most of the capsules are outside of the cells and exhibit red fluorescence due to the alkaline pH of the medium. (B) The same cells after another 30 min of incubation. Capsules remaining in the cell medium retain their red fluorescence (red arrows). Capsules that were already incorporated in the acidic endosome in the first image retain their green fluorescence (green arrows). Some capsules were incorporated in endosomal/lysosomal compartments inside cells within a period of 30 min, which is indicated by their change in fluorescence from red to green (red to green arrows). Both images comprise an overlay of microscopy images obtained with phase contrast, a red and a green filter set. (C) Schematic presentation of the endocytotic capsule uptake. Reprinted with permission from Kreft et al.37 they have incorporated a competitive fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay in the microcapsules’ cavity. This technique is based on the competitive replacement of one partner of the FRET couple by the analyte, resulting in a decrease in the amount of fluorescence measured that correlates with the amount of analyte present. In a first attempt, these authors incorporated TRITC-labeled con A, a sugar binding lectin, and FITC-dextran (FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate) as a FRET couple in the microcapsules’ shell. In the presence of glucose, FITC-dextran became displaced from Con A, resulting in a decrease of FRET efficiency that could be correlated to glucose concentration.33 As this system lacked robustness the authors have optimized their concept36 using apo-glucose oxidase instead of Concanavalin A.36 Apo-glucose oxidase is the inactive form of the glucose oxidase enzyme, which lacks catalytic activity but retains a high binding affinity for b-D-glucose. TRITC-labeled apo-glucose oxidase and FITC-dextran were loaded simultaneously in polyelectrolyte capsules and formed complexes in the capsules’ interiors. Addition of glucose, which freely diffuses through the capsules’ membrane due to its low molecular weight, induced decomplexation between the TRITCapo-glucose oxidase and the FITC-dextran resulting in a decrease in FRET efficiency from which the glucose concentration can be estimated. Conclusions In this paper we have reviewed several contributions made in the field of polyelectrolyte microcapsules for the purpose of This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 biomedical applications ranging from drug delivery to sensing purposes. Whereas the advent of polyelectrolyte capsules in 1998 was followed by the thorough characterization of capsules’ physicochemical applications there are now more and more systems coming to a point where they could start to play a role in a biomedically relevant context. Both low molecular weight (such as the chemotherapeutics doxorubicin and daunorubicin) as well as high molecular weight drugs (such as e.g. protein antigens) can be encapsulated inside the capsules and delivered to living cells in vitro. Although it is clearly possible to use polyelectrolyte microcapsules for intracellular delivery of different compounds, their exact cellular localization and possible endosomal escape to the cytosol have not yet been thoroughly addressed. Similarly, it remains unknown if these capsules can be applied to transfect cells. Moreover, little is known about their in vivo behaviour. As was demonstrated by De Koker et al.,30 microcapsules composed of the biodegradable polyelectrolytes poly-L-arginine and dextran sulfate induce a moderate inflammatory reaction after subcutaneous injection. Although this may well be an interesting feature for vaccination purposes, it is an unwanted side effect for most other applications including drug delivery. The same study also demonstrated that these capsules are readily taken up by mononuclear phagocytes, similar to other particles in this size range. In many cases, it may be attractive to target microcapsules and their contents towards other cells, e.g. tumor cells. In vitro uptake of polyelectolyte capsules by tumor cells has been described by several authors, either with or without targeting antibodies. However, their size and polyionic nature raise important issues for in vivo intraveneous administration. Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 | 289 However the deformability of polyelectrolyte microcapsules upon shear stress and flow through constricted pores has been demonstrated,123,124 to the best of our knowledge, circulation of polyelectrolyte capsules in the bloodstream after intraveneous injection has not yet been reported in the literature. In case the capsules would be small enough, i.e. below 200 nm, and shielded from protein adsorption and uptake by macrophages, they could be applied for the delivery of therapeutic agents to tumor cells exploiting the EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect (i.e. leaky vasculature in tumor tissue). Such small capsules with diameters down to 50 nm have been reported by Schneider and Decher125 which should, at least theoretically, make it possible to fabricate polyelectrolyte microcapsules which could freely circulate in the blood stream and make use of the EPR effect. For the scientists active in the field of polyelectrolyte capsules this offers an exciting challenge to take advantage of the unique properties of these capsules to develop highly sophisticated drug delivery or biosensor systems which are unmet by any other fabrication technique. Moreover this would also elucidate for which specific applications polyelectrolyte capsules would be really advantageous compared to more established drug delivery systems such as liposomes, micelles and polymeric particles. References 1 F. Caruso, R. A. Caruso and H. Mohwald, Science, 1998, 282, 1111– 1114. 2 E. Donath, G. B. Sukhorukov, F. Caruso, S. A. Davis and H. Mohwald, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 1998, 37, 2202–2205. 3 C. S. Peyratout and L. Dahne, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2004, 43, 3762–3783. 4 G. B. Sukhorukov, E. Donath, S. Davis, H. Lichtenfeld, F. Caruso, V. I. Popov and H. Mohwald, Polym. Adv. Technol., 1998, 9, 759– 767. 5 G. B. Sukhorukov and H. Mohwald, Trends Biotechnol., 2007, 25, 93–98. 6 G. Decher, Science, 1997, 277, 1232–1237. 7 K. Ariga, J. P. Hill and Q. M. Ji, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2007, 9, 2319–2340. 8 B. G. De Geest, N. N. Sanders, G. B. Sukhorukov, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2007, 36, 636–649. 9 S. A. Sukhishvili, Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci., 2005, 10, 37–44. 10 G. B. Sukhorukov, A. L. Rogach, B. Zebli, T. Liedl, A. G. Skirtach, K. Kohler, A. A. Antipov, N. Gaponik, A. S. Susha, M. Winterhalter and W. J. Parak, Small, 2005, 1, 194–200. 11 A. S. Angelatos, K. Katagiri and F. Caruso, Soft Matter, 2006, 2, 18–23. 12 B. G. De Geest, A. M. Jonas, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Langmuir, 2006, 22, 5070–5074. 13 H. G. Zhu and M. J. McShane, Langmuir, 2005, 21, 424–430. 14 D. G. Shchukin, T. Shutava, E. Shchukina, G. B. Sukhorukov and Y. M. Lvov, Chem. Mater., 2004, 16, 3446–3451. 15 B. G. De Geest, B. G. Stubbe, A. M. Jonas, T. Van Thienen, W. L. J. Hinrichs, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 373–379. 16 M. Fischlechner, L. Toellner, P. Messner, R. Grabherr and E. Donath, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2006, 45, 784–789. 17 M. Fischlechner, O. Zschornig, J. Hofmann and E. Donath, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2005, 44, 2892–2895. 18 K. Katagiri and F. Caruso, Adv. Mater., 2005, 17, 738. 19 S. Moya, E. Donath, G. B. Sukhorukov, M. Auch, H. Baumler, H. Lichtenfeld and H. Mohwald, Macromolecules, 2000, 33, 4538– 4544. 20 D. G. Shchukin and G. B. Sukhorukov, Adv. Mater., 2004, 16, 671– 682. 21 D. G. Shchukin, G. B. Sukhorukov and H. Mohwald, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2003, 42, 4472–4475. 290 | Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 22 D. G. Shchukin, E. A. Ustinovich, G. B. Sukhorukov, H. Mohwald and D. V. Sviridov, Adv. Mater., 2005, 17, 468. 23 A. A. Antipov and G. B. Sukhorukov, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2004, 111, 49–61. 24 Y. Lvov, A. A. Antipov, A. Mamedov, H. Mohwald and G. B. Sukhorukov, Nano Lett., 2001, 1, 125–128. 25 G. Sukhorukov, L. Dahne, J. Hartmann, E. Donath and H. Mohwald, Adv. Mater., 2000, 12, 112–115. 26 G. B. Sukhorukov, A. A. Antipov, A. Voigt, E. Donath and H. Mohwald, Macromol. Rapid Commun., 2001, 22, 44–46. 27 A. I. Petrov, D. V. Volodkin and G. B. Sukhorukov, Biotechnol. Prog., 2005, 21, 918–925. 28 Y. J. Wang and F. Caruso, Chem. Mater., 2005, 17, 953–961. 29 G. B. Sukhorukov, M. Brumen, E. Donath and H. Mohwald, J. Phys. Chem. B, 1999, 103, 6434–6440. 30 S. De Koker, B. G. De Geest, C. Cuvelier, L. Ferdinande, W. Deckers, W. E. Hennink, S. C. De Smedt and N. Mertens, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2007, 17, 3754–3763. 31 B. G. Stubbe, K. Gevaert, S. Derveaux, K. Braeckmans, B. G. De Geest, M. Goethals, J. Vandekerckhove, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Adv. Funct. Mater., DOI: 10.1002/adfm.200701039. 32 N. Kato and F. Caruso, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 19604–19612. 33 S. Chinnayelka and M. J. McShane, J. Fluoresc., 2004, 14, 585–595. 34 E. W. Stein, P. S. Grant, H. G. Zhu and M. J. McShane, Anal. Chem., 2007, 79, 1339–1348. 35 E. W. Stein, D. V. Volodkin, M. J. McShane and G. B. Sukhorukov, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 710–719. 36 S. Chinnayelka and M. J. McShane, Anal. Chem., 2005, 77, 5501– 5511. 37 O. Kreft, A. M. Javier, G. B. Sukhorukov and W. J. Parak, J. Mater. Chem., 2007, 17, 4471–4476. 38 K. Sato, Y. Endo and J. Anzai, Sens. Mater., 2007, 19, 203–213. 39 A. de Fougerolles, H. P. Vornlocher, J. Maraganore and J. Lieberman, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery, 2007, 6, 443–453. 40 S. M. Elbashir, J. Harborth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber and T. Tuschl, Nature, 2001, 411, 494–498. 41 T. R. Brummelkamp, R. Bernards and R. Agami, Science, 2002, 296, 550–553. 42 K. Remaut, N. N. Sanders, B. G. De Geest, K. Braeckmans, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Mater. Sci. Eng., R: Reports, 2007, 58, 117–161. 43 R. E. Vandenbroucke, S. C. De Smedt, J. Demeester and N. N. Sanders, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr., 2007, 1768, 571–579. 44 R. E. Vandenbroucke, B. Lucas, J. Demeester, S. C. De Smedt and N. N. Sanders, Nucleic Acids Res., 2007, 35. 45 A. Munoz-Javier, O. Kreft, M. Semmling, S. Kempter, A. G. Skirtach, O. Burns, P. del Pino, M. F. Bedard, J. Rädler, J. Käs, C. Plank, G. B. Sukhorukov and W. J. Parak, Adv. Mater., DOI: 10.1002/adma.200703190. 46 H. W. Duan and S. M. Nie, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2007, 129, 3333– 3338. 47 H. C. Kang and Y. H. Bae, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2007, 17, 1263–1272. 48 T. Shiraishi and P. E. Nielsen, Nat. Protocols, 2006, 1, 633–636. 49 S. Moffatt, S. Wiehle and R. J. Cristiano, Gene Ther., 2006, 13, 1512–1523. 50 P. C. Bell, M. Bergsma, I. P. Dolbnya, W. Bras, M. C. A. Stuart, A. E. Rowan, M. C. Feiters and J. Engberts, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2003, 125, 1551–1558. 51 E. Mastrobattista, G. A. Koning, L. van Bloois, A. C. S. Filipe, W. Jiskoot and G. Storm, J. Biol. Chem., 2002, 277, 27135–27143. 52 S. M. W. van Rossenberg, K. M. Sliedregt-Bol, N. J. Meeuwenoord, T. J. C. van Berkel, J. H. van Boom, G. A. van der Marel and E. A. L. Biessen, J. Biol. Chem., 2002, 277, 45803–45810. 53 C. Y. Cheung, N. Murthy, P. S. Stayton and A. S. Hoffman, Bioconjugate Chem., 2001, 12, 906–910. 54 E. A. Murphy, A. J. Waring, J. C. Murphy, R. C. Willson and K. J. Longmuir, Nucleic Acids Res., 2001, 29, 3694–3704. 55 A. ElOuahabi, M. Thiry, V. Pector, R. Fuks, J. M. Ruysschaert and M. Vandenbranden, FEBS Lett., 1997, 414, 187–192. 56 K. Ribbeck and D. Gorlich, EMBO J., 2002, 21, 2664–2671. 57 M. R. Capecchi, Cell, 1980, 22, 479–488. 58 M. van der Aa, E. Mastrobattista, R. S. Oosting, W. E. Hennink, G. A. Koning and D. J. A. Crommelin, Pharm. Res., 2006, 23, 447–459. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 59 A. Munoz-Javier, O. Kreft, A. Piera Alberola, C. Kirchner, B. Zebli, A. S. Susha, E. Horn, S. Kempter, A. G. Skirtach, A. L. Rogach, J. Rädler, G. B. Sukhorukov, M. Benoit and W. J. Parak, Small, 2006, 2, 394–400. 60 C. Kirchner, A. M. Javier, A. S. Susha, A. L. Rogach, O. Kreft, G. B. Sukhorukov and W. J. Parak, Talanta, 2005, 67, 486–491. 61 C. Kirchner, T. Liedl, S. Kudera, A. Pellegrino, A. Munoz-Javier, H. E. Gaub, S. Stölzle, N. Fertig and W. J. Parak, Nano Lett., 2005, 5, 331–338. 62 C. Picart, A. Schneider, O. Etienne, J. Mutterer, P. Schaaf, C. Egles, N. Jessel and J. C. Voegel, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2005, 15, 1771–1780. 63 E. Vazquez, D. M. Dewitt, P. T. Hammond and D. M. Lynn, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 13992–13993. 64 C. M. Jewell, J. T. Zhang, N. J. Fredin and D. M. Lynn, J. Controlled Release, 2005, 106, 214–223. 65 N. J. Fredin, J. T. Zhang and D. M. Lynn, Langmuir, 2005, 21, 5803– 5811. 66 K. C. Wood, J. Q. Boedicker, D. M. Lynn and P. T. Hammon, Langmuir, 2005, 21, 1603–1609. 67 J. T. Zhang, L. S. Chua and D. M. Lynn, Langmuir, 2004, 20, 8015– 8021. 68 C. M. Jewell, J. T. Zhang, N. J. Fredin, M. R. Wolff, T. A. Hacker and D. M. Lynn, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 2483–2491. 69 D. M. Lynn, Adv. Mater., 2007, 19, 4118–4130. 70 D. M. Lynn, Soft Matter, 2006, 2, 269–273. 71 J. T. Zhang and D. M. Lynn, Adv. Mater., 2007, 19, 4218. 72 W. Liu, J. Zhang and D. M. Lynn, Soft Matter, 2008, 4, 1688–1695. 73 B. G. De Geest, R. E. Vandenbroucke, A. M. Guenther, G. B. Sukhorukov, W. E. Hennink, N. N. Sanders, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Adv. Mater., 2006, 18, 1005. 74 D. M. Lynn, Soft Matter, 2006, 2, 269–273. 75 C. Y. Wang, S. Q. Ye, L. Dai, X. X. Liu and Z. Tong, Biomacromolecules, 2007, 8, 1739–1744. 76 Y. Itoh, M. Matsusaki, T. Kida and M. Akashi, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 2715–2718. 77 H. Lee, Y. Jeong and T. G. Park, Biomacromolecules, 2007, 8, 3705– 3711. 78 T. Borodina, E. Markvicheva, S. Kunizhev, H. Moehwald, G. B. Sukhorukov and O. Kreft, Macromol. Rapid Commun., 2007, 28, 1894–1899. 79 O. Etienne, C. Picart, C. Taddei, P. Keller, E. Hubsch, P. Schaaf, J. C. Voegel, Y. Haikel, J. A. Ogier and C. Egles, J. Dent. Res., 2006, 85, 44–48. 80 C. Dejugnat and G. B. Sukhorukov, Langmuir, 2004, 20, 7265–7269. 81 A. I. Petrov, A. A. Antipov and G. B. Sukhorukov, Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 10079–10086. 82 T. Mauser, C. Dejugnat and G. B. Sukhorukov, Macromol. Rapid Commun., 2004, 25, 1781–1785. 83 A. N. Zelikin, Q. Li and F. Caruso, Chem. Mater., 2008, 20, 2655– 2661. 84 A. N. Zelikin, A. L. Becker, A. P. R. Johnston, K. L. Wark, F. Turatti and F. Caruso, ACS Nano, 2007, 1, 63–69. 85 A. N. Zelikin, J. F. Quinn and F. Caruso, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 27–30. 86 A. N. Zelikin, Q. Li and F. Caruso, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2006, 45, 7743–7745. 87 R. Heuberger, G. Sukhorukov, J. Voros, M. Textor and H. Mohwald, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2005, 15, 357–366. 88 U. Wattendorf, O. Kreft, M. Textor, G. B. Sukhorukov and H. P. Merkle, Biomacromolecules, 2008, 9, 100–108. 89 B. Zebli, A. S. Susha, G. B. Sukhorukov, A. L. Rogach and W. J. Parak, Langmuir, 2005, 21, 4262–4265. 90 C. Cortez, E. Tomaskovic-Crook, A. P. R. Johnston, A. M. Scott, E. C. Nice, J. K. Heath and F. Caruso, ACS Nano, 2007, 1, 93–102. 91 C. Cortez, E. Tomaskovic-Crook, A. P. R. Johnston, B. Radt, S. H. Cody, A. M. Scott, E. C. Nice, J. K. Heath and F. Caruso, Adv. Mater., 2006, 18, 1998. 92 A. S. Angelatos, B. Radt and F. Caruso, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 3071–3076. 93 B. Radt, T. A. Smith and F. Caruso, Adv. Mater., 2004, 16, 2184. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2009 94 A. G. Skirtach, A. A. Antipov, D. G. Shchukin and G. B. Sukhorukov, Langmuir, 2004, 20, 6988–6992. 95 A. G. Skirtach, C. Dejugnat, D. Braun, A. S. Susha, A. L. Rogach, W. J. Parak, H. Mohwald and G. B. Sukhorukov, Nano Lett., 2005, 5, 1371–1377. 96 A. G. Skirtach, A. Munoz Javier, O. Kreft, K. Köhler, A. Alberola Piera, H. Mohwald, W. J. Parak and G. B. Sukhorukov, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2006, 45, 4612–4617. 97 X. Tao, J. B. Li and H. Mohwald, Chem–Eur. J., 2004, 10, 3397– 3403. 98 B. G. De Geest, A. G. Skirtach, T. R. M. De Beer, G. B. Sukhorukov, L. Bracke, W. R. G. Baeyens, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Macromol. Rapid Commun., 2007, 28, 88–95. 99 B. G. De Geest, A. G. Skirtach, A. A. Mamedov, A. A. Antipov, N. A. Kotov, S. C. De Smedt and G. B. Sukhorukov, Small, 2007, 3, 804–808. 100 A. G. Skirtach, B. G. De Geest, A. Mamedov, A. A. Antipov, N. A. Kotov and G. B. Sukhorukov, J. Mater. Chem., 2007, 17, 1050–1054. 101 D. G. Shchukin, D. A. Gorin and H. Moehwald, Langmuir, 2006, 22, 7400–7404. 102 B. G. De Geest, C. Dejugnat, M. Prevot, G. B. Sukhorukov, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2007, 17, 531–537. 103 B. G. De Geest, C. Dejugnat, G. B. Sukhorukov, K. Braeckmans, S. C. De Smedt and J. Demeester, Adv. Mater., 2005, 17, 2357–2361. 104 B. G. De Geest, C. Dejugnat, E. Verhoeven, G. B. Sukhorukov, A. M. Jonas, J. Plain, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, J. Controlled Release, 2006, 116, 159–169. 105 B. G. De Geest, E. Mehuys, G. Laekeman, J. Demeester and S. C. De Smedt, Expert Opin. Drug Delivery, 2006, 3, 459–462. 106 B. G. De Geest, W. Van Camp, F. E. Du Prez, S. C. De Smedt, J. Demeester and W. E. Hennink, Macromol. Rapid Commun., DOI: 10.1002/marc.200800093. 107 Z. H. Lu, M. D. Prouty, Z. H. Guo, V. O. Golub, C. Kumar and Y. M. Lvov, Langmuir, 2005, 21, 2042–2050. 108 O. Kreft, A. G. Skirtach, G. B. Sukhorukov and H. Mohwald, Adv. Mater., 2007, 19, 3142. 109 U. Kreibig, Physics and Chemistry of Finite Systems: From Clusters to Crystals, Kluwer, London, 1991. 110 A. G. Skirtach, C. Dejugnat, D. Braun, A. S. Susha, A. L. Rogach and G. B. Sukhorukov, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2007, 111, 555–564. 111 A. Gole and C. J. Murphy, Chem. Mater., 2005, 17, 1325–1330. 112 A. G. Skirtach, P. Karageorgiev, B. G. De Geest, N. Pazos-Perez, D. Braun and G. B. Sukhorukov, Adv. Mater., 2008, 29, 506–510. 113 T. V. Bukreeva, B. V. Parakhonsky, A. G. Skirtach, A. S. Susha and G. B. Sukhorukov, Crystallogr. Rep., 2006, 51, 863–869. 114 D. Radziuk, D. G. Shchukin, A. Skirtach, H. Mohwald and G. Sukhorukov, Langmuir, 2007, 23, 4612–4617. 115 K. W. Wang, Q. He, X. H. Yan, Y. Cui, W. Qi, L. Duan and J. B. Li, J. Mater. Chem., 2007, 17, 4018–4021. 116 R. Langer and D. A. Tirrell, Nature, 2004, 428, 487–492. 117 A. J. Khopade and F. Caruso, Biomacromolecules, 2002, 3, 1154– 1162. 118 X. Tao, H. Chen, X. J. Sun, H. F. Chen and W. H. Roa, Int. J. Pharm., 2007, 336, 376–381. 119 X. Y. Liu, C. Y. Gao, J. C. Shen and H. Mohwald, Macromolecular Bioscience, 2005, 5, 1209–1219. 120 Q. H. Zhao, B. S. Han, Z. H. Wang, C. Y. Gao, C. H. Peng and J. C. Shen, Nanomed: Nanotechnol. Biol. Med., 2007, 3, 63–74. 121 B. Han, B. Shen, Z. Wang, M. Shi, H. Li, C. Peng, Q. Zhao and C. Gao, Polym. Adv. Technol., 2007, 19, 36–46. 122 M. Semmling, O. Kreft, A. Munoz-Javier, G. B. Sukhorukov, J. Käs and W. J. Parak, Small, 2008, 4, 1763–1768. 123 A. L. Cordeiro, M. Coelho, G. B. Sukhorukov, F. Dubreuil and H. Mohwald, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2004, 280, 68–75. 124 M. Prevot, A. L. Cordeiro, G. B. Sukhorukov, Y. Lvov, R. S. Besser and H. Mohwald, Microfluid. BioMEMs Med. Microsyst., 2003, 4982, 220–227. 125 G. Schneider and G. Decher, Nano Lett., 2004, 4, 1833–1839. Soft Matter, 2009, 5, 282–291 | 291