Understanding the Social and Economic Lives of Never

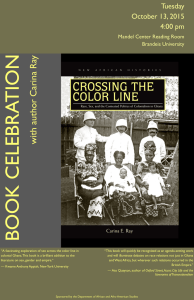

advertisement