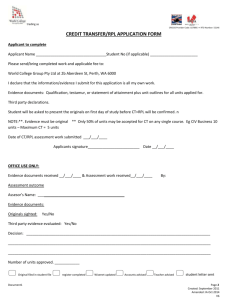

Criteria and Guidelines for the Implementation of the Recognition of

advertisement