SHINING THE LIGHT ON

ENERGY EFFICIENCY

ACHIEVING HIGHER LEVELS OF ENERGY EFFICIENCY,

INVESTING IN SOLUTIONS AND FINANCING THE

ENERGY EFFICIENCY SECTOR

PUBLIC PAPER 01

INTRODUCTION

Energy efficiency – broadly defined as a way of managing energy usage

so that more can be done with less – represents about 40 % of the

greenhouse gas reduction potential that is globally required by 2050

to prevent the earth’s temperature from increasing by more than 2 °C.1

“As the saying goes, the Stone Age did not end

because we ran out of stones; we transitioned to

better solutions. The same opportunity lies before us with energy efficiency and clean energy.”

Steven Chu, Frmr US Secretary of Energy

Interest in energy efficiency is nothing

new. Companies, governments and

consumer groups in developed and

developing markets have sought for

years to power more ecnomic activity

with less energy.

Energy efficiency is an extremely attractive area of upfront investment that pays

for itself over time, while providing the added benefits of reducing the cost of

energy and increasing the energy productivity of the economy. It is therefore not

surprising that many governments have emphasized energy efficiency opportunities during the current economic downturn as a way to stimulate their faltering

economies. By focusing funding on energy-efficient initiatives, governments hope

to not only save or create jobs – the primary goal of spending – but to also reduce

domestic dependence on foreign energy supplies and reduce carbon emissions

associated with energy use.

Interest in energy efficiency is nothing new. Companies, governments and consumer groups in developed and developing markets have sought for years to power more economic activity and residential demand with less energy. While barriers

across sectors – such as technology, financing and government regulation – have

hampered many projects and initiatives, there have also been clear successes,

such as the gradual adoption of energy-saving appliances in some markets. In recent years, increased awareness of these pockets of success – coupled with growing national competition for energy supplies, environmental concerns, increased

pressure from growing demand on an aging energy infrastructure, and advances

2

in related technologies – have prompted renewed interest in energy efficiency

among the public and private sectors. Significant injections of public funds in

energy efficiency in recent years, including public-private partnerships, have only

added to the momentum.

This paper looks at the energy efficiency opportunity and how to capture it in

emerging markets. There is a compelling opportunity to substantially lower

energy costs. Latin America could, for instance, achieve a reduction in energy

consumption of 20–25 % over the next decade if comprehensive efforts are put in

place to overcome barriers across the economy.2 Globally, the efficiency potential

is highly fragmented across more than a hundred million residential, commercial

and industrial buildings, and millions of devices. Capturing the full potential will

require global investments of around USD 500 billion per year for the next decade3

– and a holistic approach involving information and education, incentives, and

new codes and standards. Public as well as private sector engagement will

be needed. Private sector finance, in particular, will be an essential long-term

conduit for the continued expansion and evolution of the efficiency sector in the

developing world.

Capturing the global energy efficiency

opportunity will require global investments of around USD 500 billion per

year for the next decade.

International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Outlook Special Report: Energy and Climate Change,’ 2015

Latin American Energy Organization, as quoted by Sandra Guzman in ‘Energy efficiency in Latin America, the missing piece,’

2015. Available online: http://energytransition.de / 2015 / 02 / energy-efficiency-in-latin-america-the-missing-piece /

3

International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Outlook Special Report: Energy and Climate Change,’ 2015.

1

2

3

ENERGY EFFICIENCY:

UNLOCKING THE DEVELOPING

MARKET OPPORTUNITY

Significant gains await developing countries if they increase their energy

productivity: they could slow the growth of their energy demand by more

than half over the next 12 years – to 1.4 % a year, from 3.4 % at present –

which would leave demand around 25 % lower in 2020 than it would have

been. The scale of this reduction exceeds total energy consumption in

China today.4 Improvements in productivity on the back of more efficient

energy use are also the foremost drivers of long-term economic development, leading, eventually to improved livelihoods for many.

GOOD TO KNOW

Between 2008 and 2035, non-OECD

countries are expected to account for

83 % of global energy demand. China,

India and Brazil are expected to

account for 55 % of overall demand

growth.

The three basic drivers of energy demand are economic growth, population

growth and technological innovation. Longer-term trends in economic growth for

a particular economy depend on underlying demographic and productivity trends,

which in turn reflect population growth, labor force participation, productivity

growth, national savings rates and capital accumulation. It is therefore unsurprising that emerging economies are expected to account for a major part of the

growth in energy demand in the coming decades: as they move from poverty to

middle income status, there is a fundamental shift from agriculture to more energy-intensive commercial enterprises. For the first time in history, the majority

of the world’s population has become urbanized, with the largest urban centers

emerging in developing regions where energy costs remain a serious constraint.

Outside urban areas access to energy sources remains a challenge. By 2050, the

global population is expected to increase to 9.3 billion. Virtually all of this projected growth will occur in the developing world.5 Between 2008 and 2035, non-Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries are expected

to account for 83 % of energy demand; together, China, India, and Brazil are expected to account for 55 % of overall demand growth.6 Non-OECD demand growth in

the rest of the world accounts for 28 % of the world total.

McKinsey & Company, ‘Energy Efficiency: A compelling global resource,’ 2010.

United Nations Population Fund, ‘Annual Report 2011: Delivering Results in a World of 7 Billion,’ 2012.

6

Ibid.

4

5

4

“We do not yet fully understand the consequences of rising

populations and increasing energy consumption on the

interwoven fabric of atmosphere, water, land and life.”

Martin Rees, British astrophysicist

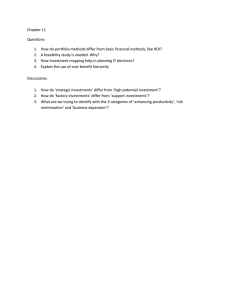

Projected world energy consumption

900

800

700

Quadrillion Btu

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Year

1990

2000

2010

non-OECD countries

2015

2020

2030

2040

OECD countries

Figure 1 Source: International Energy Outlook, 2014

Energy demand on this scale will put increasing pressure on global energy resources and distribution networks. This is unsustainable without a fundamental

transformation of the global energy system; the dominant fossil energy resources

today, especially oil, are concentrated in only a few regions. Many governments

therefore see energy security – i. e. potential disruptions in supply – as a potential

threat to their economic well-being. In Zambia and South Africa, for example, the

lack of an adequate energy supply has in recent years resulted in rolling power

outages, with costly effects for the mining industry in both countries. In August

2015, Zambia’s copper mining industry, which consumes more than half of the

country’s total electricity output, agreed to cut demand by 30 %. On the back of

these disruptions, copper output is expected to fall by 15 % in 2016.7 The kind of

energy transformations needed to meet growing demand are costly. Various models estimate that it could cost USD 1100 billion through 2050 in developed markets,

with even higher costs in less developed regions.8 Before systems are transformed,

it is therefore imperative to maintain demand in a sustainable and efficient manner

– i. e. to do more with less.

7

8

The current scale of energy demand is

putting increasing pressure on global

energy resources and distribution networks. This is unsustainable without

a fundamental transformation of the

global energy system.

Capital Economics, ‘Zambia: Problems under the hood.’ Africa Economics Update, 11 September 2015.

Henning, Hans-Martin. ‘What will the energy transformation cost? Pathways for transforming the German Energy System by 2050.’

Fraunhofer-Institut für Solare Energiesysteme ISE, Press Release 28 / 15, 15 December 2015.

5

ENERGY SAVINGS

75 %

One very simple example of energy-efficient investments is Ghana’s appliance

labelling program under which appliances are labelled to indicate to consumers

the energy consumption and efficiency of the products. Launched in 2000, these

efforts have thus far resulted in a reduction of peak energy demand of over

120 mega-watts (MW) and have displaced the need for USD 105 million in generation investment. From 2005 to 2012, similar energy efficiency incentive programs

in South Africa reduced peak electricity demand by 3 gigawatts (GW).9 According

to McKinsey & Company, just by using existing technologies that would pay for

themselves in future energy savings, consumers and businesses in emerging

markets could save around USD 600 billion a year trough 2020.10 These savings are

achievable with an investment of USD 90 billion annually over the next 12 years –

only half of what these economies would otherwise need to spend on their energy

supply infrastructure to keep pace with higher consumption.

Higher levels of energy efficiency are

attainable either trough reductions

in the energy consumed to produce

the same level of energy services or

by increasing the quantity and quality

of economic output produced by the

same level of energy services.

Indeed, higher levels of energy efficiency are attainable either by reductions in the

energy consumed to produce the same level of energy services (e. g. a refrigerator

in Ghana produces the same cooling output for less energy input), or by increasing

the quantity and quality of economic output produced by the same level of energy

services (e. g. providing higher-value added services in the same office building).

This is true on a household as well as an industrial scale. Many manufacturing

companies in the emerging markets can, for example, improve the overall energy

efficiency of their operations by 10 % or more with relatively small investments

and by up to 35 % when making substantially larger ones.11 Savings, of course, vary

by sector. One Mexican chemical company, for example, estimates that it can trim

7 % off its energy costs at a cost of less than USD 30 million.12 Iron and steel companies can save around 10–30 % of their annual energy consumption and reduce

their costs through better energy management, often just by making operational

changes.13 Research conducted by the global technology firm Siemens suggests

that energy savings of 5 % are possible in the glass industry14 – a sector that is

becoming increasingly vital to the Ethiopian economy. This represents a savings

of 6 terawatt hours per year for the global glass industry – approximately the same

level of energy consumption as a city with a population of five million.15

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, ‘Energy Efficiency Country Study: Republic of South Africa’, 2013.

McKinsey & Company, ‘Energy Efficiency: A compelling global resource,’ 2010.

11

Ibid.

12

Private interview conducted by responsAbility Investments AG, 7 March 2016.

13

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) (2013), Large industry Energy Network (LIEN) Annual Report 2012.

DSTI / SU / SC(2014)14 / FINAL 30 Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (2011), Large industry Energy Network (LIEN) Annual

Report 2010. McKane, A., D. Desai, M. Matteini, W. Meffert, R. Williams, and R. Risser (2009), Thinking Globally: How ISO 15001

– Energy Management Can Make Industrial Energy Efficiency Standard Practice, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

14

Siemens, ‘Energy efficiency raises productivity. Glass: Answers for industry’ 2008.

15

Ibid.

9

10

6

A NECESSARY LONG-TERM

ENABLING FRAMEWORK

Until recently, a range of market failures and information barriers has

discouraged emerging economies from increasing their energy productivity: 1) fossil fuel subsidies; 2) a lack of adequate consumer information; 3) technological barriers; and 4) tight credit markets. At the same

time, however, progress in each of these areas has increasingly opened

up the energy efficiency space as an attractive long-term growth market and an equally interesting investment opportunity. In fact, 65 % of

all available positive-return opportunities to boost energy productivity

can now be found in the developing regions.16

KEEP IN MIND

In 2005, fossil fuel subsidies in developing countries totalled more than USD

250 billion annually. Governments in

the developing world have pursued

such subsidies as a way of promoting

industrialization and of protecting the

poor from high energy prices. However,

the upshot of these efforts has been

the reverse effect.

REMOVING FOSSIL FUEL SUBSIDIES

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that in 2005, fossil fuel subsidies

in developing countries totalled more than USD 250 billion annually – more than

the annual investment needed to build their electricity supply infrastructure.17 In

the Middle East and North Africa, such subsidies in 2011 amounted to over 8.5 % of

regional GDP, or 22 % of total government revenue. Developing countries in Asia

made up over 20 % of global energy subsidies the same year – equivalent to nearly

1 % of regional GDP.18 Governments in the developing world have pursued such

subsidies as a way of promoting industrialization and of protecting the poor from

the stress of high energy prices. However, the upshot of these efforts has been

the rapid depletion of energy resources, overstretched government budgets and

depressed investments in potential energy efficient solutions. Energy demand has

only continued to increase. As they are regressive in nature, most subsidy benefits

have been captured by higher-income households, actually reinforcing inequality.

In recent years, however, there has been a major international push to identify and

reduce such distortionary policies at a national level. In July 2013, for example, Latvia’s Cabinet of Ministers passed amendments requiring a significant reduction in

natural gas plants’ subsidies. Countries including Turkey, Armenia, the Philippines,

Brazil, Chile, Peru, South Africa, Kenya and Uganda have all attempted to push

energy subsidy reforms. Indeed, government leaders increasingly recognize the

financial and economic benefits of curbing energy demand. The reasons vary from

country to country. For some, the savings generated through energy efficiency can

be used for other economic activities in the private and public sectors. For others,

diversifying the fuel mix to include more renewable sources is more cost effective

than consuming more fossil fuels. In India, for example, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency in 2008 established Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT), an incentive scheme

McKinsey & Company, ‘Energy Efficiency: A compelling global resource,’ 2010.

International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Investment Outlook 2014: Special Report,’ 2014.

18

Sdralevich, Carlo, Randa Sab, Younes Zouhar, and Giorgia Albertin, ‘Subsidy Reform in the Middle East and North Africa:

Recent Progress and Challenges Ahead.’ Washington DC: International Monetary Fund, 2014.

16

17

7

Governments are increasingly providing incentives for utilities to improve

energy efficiency and encourage their

customers to do the same.

to encourage energy savings in nearly 500 factories across eight industries.19 The

PAT scheme is, in some respects, similar to the emissions trading schemes in parts

of Europe and North America: companies that save more energy than their targets

receive energy savings certificates that they can sell to companies that miss their

goals. It is estimated that the PAT scheme could result in savings of as much as

12.5 % of India’s total energy consumption.20

INCREASED CONSUMER INFORMATION

Governments are increasingly providing incentives for utilities to improve energy

efficiency and encourage their customers to do the same. Policies include revenue

incentives and certification programs that measure and reward progress toward

achieving efficiency targets and also encourage the adoption of technologies

such as smart metering that help households to better manage their energy use.

In Latin America, for example, Ecuador is aiming to make smart meters ubiquitous

by 2017.21 Such systems have already been adopted in Brazil as a way to mitigate

electricity theft and fraud, a widespread problem in the region.22 In countries like

Egypt, too, the sale of incandescent lights is gradually being phased out; Egypt

intends to roll out a large-scale lighting upgrade after 2020 and to use energy efficient products to replace traditional lighting.23

In various parts of the developing world, governments are also adopting mandatory appliance-labelling schemes like that in Ghana in an effort to empower

consumers to make energy-efficient choices. Such programs have proven successful in regions where they have been in place for some time. In 1993, for instance,

the Thai national electric power utility Energy Generating Authority of Thailand

(EGAT) launched a comprehensive five-year energy management programme,

which included the mandatory labelling of energy efficient refrigerators. EGAT

first negotiated with manufacturers a voluntary labeling scheme for refrigerators

that awarded refrigerators a label designating efficiency from level 1 to level 5

(wherein which level 5 was the most efficient). EGAT also sponsored an advertising

campaign to promote the label and partnered with a Thai technical standards

institute to test domestically available refrigerators. A few years later, the label

scheme was made mandatory, and EGAT reached agreement with the manufacturers to increase by 20 % the efficiency requirements for each label level. By 2000,

all single-door and 60 % of two-door refrigerator models met level 5 requirements,

contributing to an estimated 21 % reduction in overall refrigerator energy consumption.24

The Polish Efficient Lighting Initiative, spearheaded by the World Bank, promoted

a ‘green leaf’ product logo to identify high-quality and environmentally friendly

products. In China, consumer education is fostered through retailer displays, product labels and a series of books on efficient lighting design for households and

small businesses. Technological advances are also generating heightened consumer awareness, as well as new ways of understanding how energy in the emerging

markets is used.

Power, fertilizer, cement, iron and steel, chlor-alkali, aluminum, textile, and pulp and paper.

Center for Clean Air Policy, ‘CCAP Success Stories: India and Waste Sector,’ October 2012.

Electric Light & Power, ‘Smart metering investments to jump in South America,’ 10 June 2013. Available online:

http://www.elp.com / articles / 2013 / 06 / smart-metering-investments-to-jump-in-south-america.html

22

O’Toole, Sean. ‘Revenue-securing technology for Latin America,’ The Siemens Customer Magazine, 1 October 2015.

Available online: https://www.siemens.com / customer-magazine / en / home / energy / power-transmission-anddistribution / revenue-securing-technology-forlatin-america.html

23

Chen, Skavy. ‘Top three emerging LED markets with huge economic potential,’ LEDInside, 22 September 2015.

Available online: http://www.ledinside.com / outlook / 2015 / 9/ledinside_top_three_emerging_led_markets_with_huge_

economic_potential

24

Briner, Sabrina and Eric Martinot, ‘Market transformations for energy-efficient products: lessons from programs

in developing countries.’ Energy Policy, 2003.

19

20

21

8

BREAKING DOWN TECHNOLOGICAL BARRIERS

Indeed, discussions of technological advancements in energy efficiency tend to

focus on equipment upgrades and improvements in the physical components of

facilities. This is suited to the here and now: at a household level, LED lights can

now produce between 50 and 100 lumens per watt (lm / W) in normal working conditions. A traditional 60-watt incandescent bulb can produce about 750 to 1,000 lumens but 95 % of the energy used to create that light is typically wasted in heat.25

The payback on investments in LED lighting is typically between one and three

years. Within industry, efficiency upgrades to compressed air systems, for example, that are used for purposes as diverse as heating and cooling, railway breaking

systems, and scuba diving, can recover 50 % to 90 % of lost thermal energy; more

than 85 % of electrical energy input into air compressors is usually lost as waste

heat, leaving less than 15 % of the electrical energy consumed to be converted into

compressed air energy.26

Increasingly, however, a holistic and system-wide approach that leverages advancements across various technologies is starting to define the energy efficiency

business. Advancements in metering (often by way of connection with mobile

phones) is one immediate example: the deployment of advanced metering infrastructure can increase the rate and volume of data generation. According to GTM

Research’s report “The Soft Grid 2013–2020: Big Data & Utility Analytics for Smart

Grid,” advanced meters create nearly 2,000 times the amount of data at 15-minute

intervals compared to the traditional monthly readings of conventional meters.27

Such data can help companies make better energy decisions that result in financial and environmental gains. While such technologies are so far confined primarily to developed economies, their translation into the emerging market context

should be achievable in the future.

KEEP IN MIND

Increasingly, a holistic and systemwide approach that leverages advancements across various technologies is

starting to define the energy efficiency

business.

Fisher, Lucy and Matthew Wall, ‘Energy-saving technologies cutting firms’ fuel bills.’ BBC News, 9 May 2014.

Available online: http://www.bbc.com / news / business-27292314

26

Csanyi, Edvard ‘11 Energy-Efficiency Improvement Opportunities In Compressed Air Systems,’

Electrical Energy Portal, 24 July 2015.

27

Lacey, Stephen, ‘Intelligent Efficiency: Innovations Reshaping the Energy Efficiency Market.’ Greentech Efficiency, 2013.

25

9

FINANCING

ENERGY EFFICIENCY

Financing large numbers of attractive energy efficiency projects has

proven difficult, primarily because the intrinsic nature of the projects

and their broader setting make it hard for effective markets to develop

naturally. As discussed, in some countries, price distortions may undermine incentives but in a growing number of other markets, this is not

the case as a significant number of projects with attractive financial

returns exists.

The major proportion of energy

efficiency finance is provided by the

private sector, much of it in the form

of traditional traditional commercial

bank financing to businesses or

households.

In markets like Brazil, China and India, the primary issue is one of bringing strong

expertise to bear: for energy-efficient investments to be made, energy efficiency

concepts must be marketed and specific projects identified, designed and evaluated. This requires marketing, project development, and technical assessment

skills, typically provided by energy efficiency experts. For markets such as these,

the main challenge is how to most efficiently access existing project development

capacity.28

The energy efficiency finance landscape is large and diverse, and is a critical part

of the resources needed to support the efficiency market. To date, the major proportion of energy efficiency finance is provided by the private sector, much of it in

the form of traditional commercial bank financing to businesses or households.29

The most basic types of finance are debt, grants, guarantees and equity:

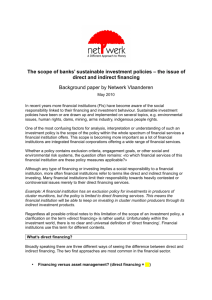

Annual green bond issuance by issuer type

Energy/utility companies

40

Coporates/banks

35

Other government/agency/local

KfW Bankengruppe

Equity, USD bn

30

Other Multilateral Development

Banks (MDB)

25

European Investment Bank (EIB)

20

International Finance (IFC)

World Bank (IBRD)

15

10

5

0

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Figure 2 Data from Bloomberg and the World Bank; compiled by Julian Spector in ‘The Rise of Green Gonds, Explained.’

CityLab 11 August 2015.

10

■ Debt: can be provided by the private or public sector in a

variety of ways, from simple consumer loans to more complex models such as pooled loans and on-bill financing.

Private financial institutions provide loans at market rates,

whereas public institutions more often – but not always –

provide concessional loans, e. g. at preferential rates. Funding from a private bank at a market interest rate can also

be combined with public funding at below-market rates. A

particular form of debt often used in the energy efficiency

context is provided through dedicated credit lines. These

lines typically involve public sector financing and are

often used when private commercial banks are not financing many energy efficiency projects (e. g. due to a lack of

knowledge and understanding of their characteristics, or

limited liquidity).

(Green) bonds: are another form of debt; these transactions typically involve a contractually more distant and

remote relationship between the lender, i. e. the public

or private financial institutions, and the borrower. Like

any other bond, a green bond is a fixed-income financial

instrument for raising capital through the debt capital

market. In its simplest form, the bond issuer raises a fixed

amount of capital from investors over a set period of time,

repaying the capital when the bond matures and paying

an agreed amount of interest (coupons) along the way. The

key difference between a ‘green’ bond and a regular bond

is that the issuer publicly states it is raising capital to fund

‘green’ projects, assets or business activities with an environmental benefit. Green bonds are becoming increasingly

prominent in the energy efficiency area: they have been

issued by a variety of issuers, with a sharp increase in issuances in 2014.

■ Guarantees and other credit support mechanisms

(insurance, derivatives) reduce or spread the risk of project

debt. A guarantee is designed to encourage the lender

(such as a commercial bank, for example) to provide a

loan; normally these loans can be provided at a preferential rate as a result of credit enhancement mechanisms,

or are provided only with the enhancement in the first

place. Guarantees for energy efficiency are typically established by public entities to catalyze private investment.

(see Figure 2)

■ Grants are funds provided without any repayment obligation. In the context of energy efficiency, they are typically

used for small-scale projects to incentivize households or

businesses. They may cover all or part of an investment,

e. g. in a specific piece of energy-efficiency equipment.

Grants are generally public funds used, for example, to

lower the capital requirements of an energy efficiency

activity that would otherwise (potentially) not be carried

out. Grants are often required to cover transaction costs

associated with energy efficiency investments (such as energy audits and subsequent monitoring and verification),

particularly when they are high relative to the size of the

underlying transaction. For example, a USD 2,000 rebate

for installing an energy-efficient boiler both reduces the

upfront capital requirement and improves the risk / return

profile of the investment.

■ Equity entails funding from investors who participate in

a company; it represents an infusion of cash into the company without a contractual repayment obligation but with

a potential revenue stream from dividends or enhanced

stock sale values. A number of energy-efficient projects

are financed through project companies, which may later

acquire energy-efficient assets. Equity is expected to be an

increasingly important source as markets develop.

Yeager, Kurt et al., ‘Energy and Economy’ in Global Energy Assessment – Toward a Sustainable Future. Cambridge UK and

New York NY: Cambridge University Press and International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria, 2012.

29

International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Investment Outlook 2014: Special Report,’ 2014.

28

11

FINANCING

KEEP IN MIND

While the public sector can develop

policy and regulatory instruments to

overcome barriers and facilitate the

scaling-up of investment in energy

efficiency projects, it is private sector

finance that remains key for the longterm growth of the sector.

12

Two approaches are being taken by commercial banks: demand-driven and

strategy-driven approaches. The demand-driven approach involves repackaged

product extensions, such as lending for commercial refits, mortgages extended

to cover energy efficiency, or car loans for more energy-efficient cars. The strategy-driven approach assesses whether energy efficiency product types and target

markets fit within a bank’s existing strategy or portfolio mix. An example of the

strategy-driven approach would be to introduce energy efficiency lending products as part of a multi-tiered programme to grow the SME business segment, with

the objective of diversifying revenue and credit risk. The objective of the strategy-driven approach is to realize that existing clients’ risk profile, and profitability

can be improved by enhancing energy through measures such as replacing inefficient machinery to benefit industrial clients.

Commercial banks also play an important role in channelling public finance towards energy efficiency. Many development banks, for example, channel funds

through local commercial banks, which in turn often provide complementary

financing. This, for example, is the case for the various risk-sharing facilities in

which commercial banks mobilize the actual liquidity that benefits from guarantee coverage. While the public sector can develop policy and regulatory instruments to overcome barriers and facilitate the scaling-up of investment in energy

efficiency projects, it is private sector finance that remains key for the long-term

growth and development of the energy efficiency market. Other sources are also

emerging, including institutional investors who look for long-term investments

with medium-term returns and low risk.

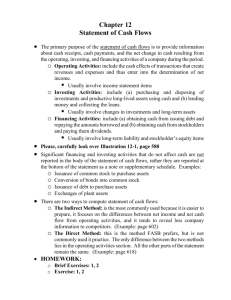

Private finance instruments, USD bn

Grants 3 %

Balance sheet

financing 48%

Low-cost

debt 22 %

Project-level

equity 5 %

Project-level market

rate debt 22%

Figure 3 Source: Climate Policy Initiative, “The Global Landscape of Climate Finance,” 2014.

CONCLUSION

It is easy to get excited about energy efficiency opportunities in emerging

markets. Proven pockets of success, growing economies, improving regulatory

environments and technological advances are all driving the potential of energy

efficient solutions. As markets mature, a vast number of companies, public institutions, and public and private financiers are are opening the way for a paradigm

shift based on more efficient energy usage. As utilities and other providers obtain

more information about how their consumers operate, the potential for efficiency

also increases. The examples mentioned in this paper represent only a small part

of the progress in the field of innovation and opportunity. Here, private sector

financing is especially important when it comes to deploying the long-term capital

needed to foster advances in efficiency, to reach end-users.

Embracing energy efficiency as a long-term growth sector in emerging markets is

still a new concept for many. However, the opportunities are there. Just like novel

microfinance investment vehicles unlocked previously inaccessible financing

resources for individuals at the base of the pyramid, governments, companies

and financiers are uncovering a deep well of energy efficiency opportunities that

are slowly reshaping the way individuals and businesses in the developing world

think about how they use energy. We have only begun to scratch the surface of

what can be achieved.

13

FINANCING ENERGY EFFICIENCY

Antoine Prédour oversees development investments

in the energy sector globally at responsAbility Investments AG. He explains how successful results can be

achieved when investing in energy efficiency.

W

here do you see the greatest potential for development investments in the area of energy efficiency?

Let me give you some examples. The

first is air-conditioning systems, which

are a key topic in developing countries

and emerging economies with a hot

climate. These systems often waste a

lot of energy due to the use of outdated

technology. In Nicaragua, one university has therefore replaced all of its air

conditioning systems with the latest

models, has insulated all the rooms

in its buildings and has fitted better

windows and ceilings. As a result, the

rooms are now cooler, students are

performing better and the university

has reduced its energy bills by more

than 30 %. The investment paid off in a

very short period of time as a result of

electricity savings.

In many countries, firms use emergency

generators to cope with power cuts.

These generators tend to use large

quantities of diesel. In the Dominican

Republic, we are working with a partner bank to develop a programme to

enable hybrid machines to be used.

During the day, these machines run on

green solar energy, significantly reducing CO2 emissions.

In San José in Costa Rica, we are planning to replace old buses used for

public transport with new vehicles that

mainly run on natural gas. This means

that green fuel will be used in the new

buses. These vehicles also consume less

energy and are safer.

14

The fourth example is the replacement

by Indian farmers of the existing irrigation systems in their fields with

energy-efficient drip irrigation systems.

These modern systems are better for

the soil and also lead to increased crop

yields. The estimated amount of water

saved is 47 % in fields of sugar cane and

33 % on banana plantations.

Y

ou make these investments possible. What are the main challenges

you face?

The greatest challenge is to ensure

that the need for energy efficiency is

entrenched in people’s minds. If we can

convince decision-makers of the potential of state-of-the-art energy solutions,

this opens the way for investments and

makes it possible to seize economic

opportunities.

At responsAbility, we strive to raise

awareness of energy efficiency – primarily in our dialogue with top managers. They are often unaware of ways of

lowering electricity consumption and

thus saving money. We can make progress in this area if, for example, the top

managers of a potential local financing

partner are convinced of the benefits

of energy efficiency. When talking to

them about this, we present economic

arguments, such as new market opportunities, cost savings and an enhanced

image – making them more attractive to

clients and the labour market. There is a

growing desire among people in developing countries and emerging markets

to work for ‘green companies’ and this

helps us to promote energy efficiency.

W

hat does it take to succeed when

providing financing for energy

efficiency?

Many developing countries and emerging economies are growing rapidly.

Decision-makers in these countries

face major management challenges

on a daily basis. This means we must

first capture their attention if we want

to approach them about a new topic.

Once we get to the point of being able

to show them the business case, this

represents a major step forward.

Many of these financial intermediaries

do not yet have engineers with expertise in the area of energy efficiency. Co

investments can therefore make sense

at first. They give our partners the guarantee that we share the same goals, are

there to support them and will train

their specialists in the process.

In a new market, it is typical for public

sector funds to lead the way and make

the first investments. Private investors

come later and significantly leverage the

impact of the initial investments. Our

role is to open up these opportunities

for investment and to present attractive

projects to private investors. Our local

partners define the niche area that they

believe offers significant potential and

is highly scalable. They then carry out

initial financing to test the market and

scale up their offering from there.

“We all stand to benefit when

we identify potential, supply

additional capital and thus

facilitate increased financing.”

Antoine Prédour

Y

ou define yourself as a partner to

local banks. What does that mean?

Being a partner is all about engaging

with one another on equal terms and

joining forces to enter new markets.

Our partner banks share the same

interests as responsAbility and the

companies that invest with us. We all

stand to benefit when we identify new

potential, supply additional capital and

thus facilitate increased financing.

responsAbility’s Antoine Prédour oversees financing projects in the energy sector globally.

Measures to improve energy efficiency

require long-term access to capital. It is

a question of finding investors who are

prepared to make a long-term commitment and can act as reliable partners to

local banks.

Y

ou consider the provision of technical assistance to be important.

How does it contribute to the success

of financing?

In 2015, we carried out 16 Technical

Assistance projects. For example, specialists selected by responsAbility are

offering practical support and advice to

a local bank that is setting up a green

lending programme.

Our Technical Assistance teams are advising the bank on the implementation

of green lending, the analysis of market

potential and the development of new

products.

Our Technical Assistance offering is

financially viable for us because we

use it in a very targeted way. It is only

deployed in a brief start-up phase and

helps our partners to swiftly become

independent. This is invaluable for us

and our investors since local partners

can then further develop the market

on their own. All of our joint activities

focus on achieving increased energy

efficiency and on realizing specific

profit targets and key performance

indicators. Other institutions also offer

technical assistance. If, in a next step,

we could work together to ensure that

our activities as market participants are

better coordinated, we could achieve

an increased impact.

In specific terms, this partnership

means that we don’t interfere with

the business models of the banks concerned. They know their market and

their organization and we trust their

approach. We see ourselves solely as a

consultant who is there to advise them

on their new green lending business.

Equally, we don’t try to implement one

standard process. Instead, we concentrate on making the most valuable

contribution we can: We demonstrate

the business potential of development

investments in the area of energy efficiency and we assist them in finding

and financing lucrative projects.

Reliability and the rapid execution of

processes is what local financial intermediaries want from us. Our role is to

provide technical advice and to arrange

the supply of long-term capital. It

makes a big difference to them whether they can focus their green lending

programme on a two or ten-year horizon. They also want a partner who is

able to finance the growth of their

programme at a later point in time.

15

OUR OFFICES

March 2016

SWITZERLAND, ZURICH (HEAD OFFICE)

INDIA, MUMBAI

NORWAY, OSLO

responsAbility Investments AG

info@responsAbility.com

responsAbility India Business

asia@responsAbility.com

responsAbility Nordics AS

nordics@responsAbility.com

BRANCH OFFICE, GENEVA

KENYA, NAIROBI

PERU, LIMA

responsAbility Investments AG

info@responsAbility.com

responsAbility Africa Ltd.

africa@responsAbility.com

responsAbility America Latina S. A.C.

latam@responsAbility.com

FRANCE, PARIS

LUXEMBOURG

THAILAND, BANGKOK

responsAbility France SAS

france@responsAbility.com

responsAbility Management

luxembourg@responsAbility.com

responsAbility Thailand Ltd.

asia@responsAbility.com

HONG KONG

responsAbility Hong Kong Limited

asia@responsAbility.com

ABOUT RESPONSABILITY

responsAbility Investments AG is one of the world’s leading

asset managers in the field of development investments and

offers professionally-managed investment solutions to private,

institutional and public investors. The company’s investment

vehicles supply debt and equity financing to non-listed firms in

emerging and developing economies. Through their inclusive

business models, these firms help to meet the basic needs of

broad sections of the population and to drive economic development – leading to greater prosperity in the long term.

RESPONSABILITY RESEARCH

research@responsAbility.com

DISCLAIMER

Disclaimer: This information material was produced by responsAbility Investments

AG and / or its affiliates with the greatest of care and to the best of its knowledge

and belief. However, responsAbility Investments AG provides no guarantee with

regard to its content and completeness and does not accept any liability for losses

which might arise from making use of this information. The opinions expressed in

this information material are those of responsAbility Investments AG at the time of

writing and are subject to change at any time without notice. If nothing is indicated

to the contrary, all figures are unaudited. This information material is provided for

information purposes only and is for the exclusive use of the recipient. It does not

constitute an offer or a recommendation to buy or sell financial instruments or services and does not release the recipient from exercising his / her own judgment. This

information material may not be reproduced either in part or in full without the

written permission of responsAbility Investments AG. It is expressly not intended for

persons who, due to their nationality or place of residence, are not permitted access

to such information under local law. Neither this information material nor any copy

thereof may be sent, taken into or distributed in the United States or to any U. S.

person. It should be noted that historical returns and financial market scenarios are

no guarantee of future performance.

Texts: responsAbility Research

Interview: Dave Hertig

Editing: Tracy Turner

Photography: Willy Spiller

Design and layout: Liebchen + Liebchen GmbH

responsAbility Investments AG

Josefstrasse 59, 8005 Zurich, Switzerland

Phone: +41 44 250 99 30

www.responsAbility.com

© 2016 responsAbility Investments AG. All rights reserved.