`Fair value` for financial instruments: how erasing theory is

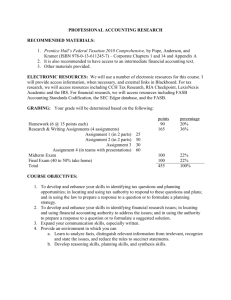

advertisement