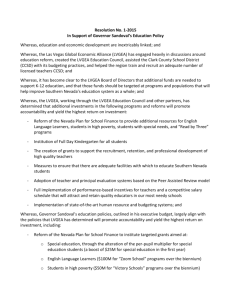

The Economic Implications of Implementing the EPA Clean Power

advertisement