Past, Present and Future Challenges of the Marine Vessel`s

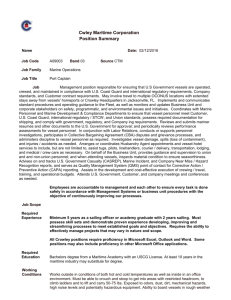

advertisement