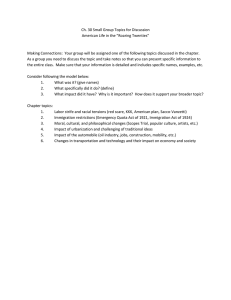

Trade, Foreign Direct Investment and Immigration

advertisement