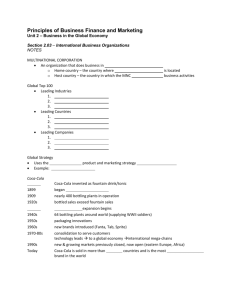

Economic Impact of the Coca-Cola System on China

advertisement