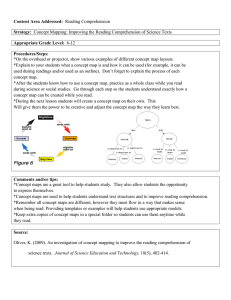

Vocabulary instruction and reading comprehension

advertisement