Techniques For Digitizing Rotary and Linear Motion

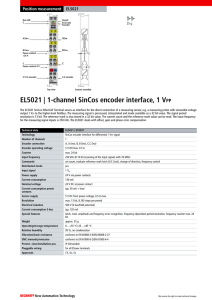

advertisement