Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain

advertisement

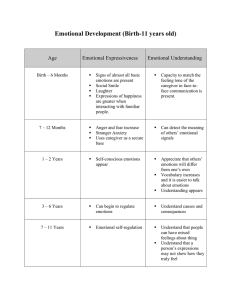

Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Ann-Bailey Lipsett ABSTRACT Before students are able to be successful with academic demands they must be able to regulate their own emotions. Seven kindergarten students at a Title One school outside of Washington, DC participated in a small-group intervention in order to increase their ability to regulate their own emotions. The curriculum for this group was created based on the neurological implications of how the brain processes emotions. “ I t’s too hard!,” Abagia, a kindergarten student groaned as I listened to my coteacher introduce a new reading activity. “I can’t do it! There is no way! I quit!” She hadn’t even started the task yet, and knowing her abilities, my co-teacher and I were very confident she would have absolutely no difficulty accomplishing the task once she began. It was getting her to begin the task that was going to be challenging. We dismissed the students to their seats by calling out their shirt colors, and as “pink” was called Abagia groaned with agony. “OH NO” she moaned, “I’ll NEVER be able to do this.” She sat at her table and picked up her pencil to write her name. By this time her anxiety was in full swing and as she wrote A her pencil wobbled. Suddenly she was banging her hand into her head, “stupid, stupid, stupid” she cried. My coteacher and I looked at each other. This was a typical morning with Abagia. Like many of the students at our school Abagia is a second-language learner who entered the United States a month before she began kindergarten. We have no idea what she experienced in her war-torn country, or exactly what her day-to-day life was like in the five years before she entered our building. Our job now is to teach this LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 157 Ann-Bailey Lipsett smart, quick-witted yet anxiety-filled five-year-old to read, count, add, and subtract. Soon after meeting Abagia, however, we realized that before we could teach her any new skills we would need to help her override her anxiety. No matter how capable she is, there was no way she could achieve academic success in kindergarten if she could not use self-calming strategies to work through frustrating situations. This is true for many of the students I work with at my diverse Title One elementary school, located just outside of Washington, DC. Before we can begin to teach content we need to ensure that our students are available for learning. To reach Abagia as well as seven other kindergarteners who also showed difficulty with emotional regulation I created an early morning social skills group using the structure for morning meetings described in the Northeast Children’s Foundation’s, Morning Meeting Book (Kriete, 2002). I relied heavily on my understanding of brain development, the regions in the brain that processes emotions, Gayle Macklem’s (2010) book, Practitioner’s Guide to Emotional Regulation in School-Age Children, as well as other texts dealing with emotional regulation in order to create a curriculum and a procedure for working with these seven students. Like most interventions in education the intervention did not solve all of Abagia’s difficulties, yet it gave her and the six others a firm base in coping with their emotions in order to allow them to be available to learn in their general education kindergarten classrooms. Understanding Emotional Regulation The term emotional regulation rarely finds its way into conversations on education policy, school reform, or even best teaching practices. The pressing focus on academic demands leaves many teachers, principals, and policy makers overlooking the importance of imbedding the teaching of emotional regulation strategies into the curriculum. This leaves our youngest students, like Abagia, without methods for coping with their emotions, making it even more difficult for them to process academic information. Gayle Macklem (2010), an educational psychologist, defines emotional regulation as how people are able to control which emotions are experienced, how and when they feel the emotions, and ways they express these emotions, both consciously and subconsciously. Emotional regulation comes into play not just in how a person expresses emotions, but in how a person is able to navigate through one’s day, what stimulus he or she will attend to, how one interprets a situation, how one 158 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation responds in situations, and in one’s general functioning. In an academic setting poor emotional regulation can affect a child’s ability to learn new material, interact with peers and adults, begin and complete tasks, and take tests. Poor emotional regulation can be seen in a child’s impulsive behavior, procrastination, and difficulty with flexible thinking. Three regions of the brain, the amygdala, the orbitofrontal area of the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus, all play a role in how emotion is processed (Gazzaniga et al., 2009). When one is presented with an environmental stressor the amygdala receives information indicating a threat. As Gazzaniga notes, the amygdala reacts by triggering both an automatic response of an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, as well as a behavioral response. A child can experience two types of reactions when met with fearful stimuli. If the child is reacting to previous memory he or she personally experienced the amygdala takes over due to its conditioned nature. A previously experienced threat will cause a child to react from experience. However, children can also react to a stimulus with fear or anxiety if they have been taught that the stimulus is a threat. In this situation the hippocampus memory system triggers the emotional response, signaling the amygdala to react and decide how to express the emotion. A child’s prefrontal cortex controls the child’s emotional recovery time, and is able to override the amygdala’s reaction to a threat, giving the child control over inappropriate behavioral responses. Importance of Emotional Regulation Research shows that a child’s emotional and behavioral regulation in preschool is a predictor of a child’s social and academic competence in kindergarten (Bulotsky-Shearer, Dominguez, Bell, Rouse, & Fantuzo, 2010). Emotional regulation can be taught to children by directly teaching them strategies. This is particularly successful at times of school transitions, such as when entering kindergarten as well as the transition to middle school. Interventions have been found to be the most successful before age seven, although children are able to develop new skills after this time as well (Macklem, 2010). Most children develop emotional regulation in the preschool years as they begin to develop language that allows them to label and express their own emotions as well as the emotions of others (Macklem, 2010). However, a child’s temperament plays a large role in the development of emotional regulation, as does a child’s LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 159 Ann-Bailey Lipsett interactions­ with his or her parents and his or her caretakers (Kagan & Snidman, 2004). A child’s background including the family’s socioeconomic status and the family’s ability to handle and cope with stress all play a role in a child’s development of emotional regulation (Dearing, 2010). A child’s previous experiences influence how the child’s hippocampus reacts to environmental stressors (Macklem, 2010). The hippocampus determines how a child will react depending on past experiences and associations stored in the child’s memory. This hippocampus reaction leads to contextdependent emotional learning. Most likely, Abagia’s background conditioned her hippocampus to react with heightened awareness and distress when presented with a novel situation, or in a situation where she is not guaranteed success. Primary teachers can support the development of emotional regulation by simply talking about emotions, labeling them, and discussing and modeling strategies for coping with these emotions (Macklem, 2010). In her book, Macklem comments that this is true for parents as well. A child’s interactions with parents and teachers have the greatest impact on a child’s emotional regulation due to the amount of time they spend with these caretakers. Emotional Regulation in the Classroom It is essential for teachers to understand the role emotional regulation plays in a child’s academic achievement and functioning in the classroom. Teachers have the power to create a positive classroom climate that allows for social and emotional skills to be taught alongside academic skills (Kauffman, 2005). However, most educators are not aware that teaching social-emotional skills will improve academic performance (Macklem, 2010). Simply managing classroom behavior in a manner that limits conduct problems is not enough to produce a change in children’s emotional regulation. In the early years it is particularly important for teachers to develop positive relationships with their students. These early relationships in school predict whether or not an individual will be able to self-regulate, develop relationships, and take different perspectives (Macklem, 2010). When children are presented with what they perceive as a stressful situation they experience a rise in cortisol. Prolonged or frequent rises in cortisol levels can damage hippocampus cells, impacting a child’s long-term memory and ability to store new information for long-term retrieval. Research shows that children who experience poor relationships with their teachers in 160 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation early grades are more likely to form fear-conditioned responses towards teachers and school within their amygdala that leads to automatic negative behavioral responses (Macklem, 2010). These automatic, neurological reactions developed early in a child’s schooling will lead to task avoidance, weak cooperation in the classroom, and children who are less likely to be self-directed. Children who experience a trusting relationship with a teacher in the early years are more likely to engage freely in exploration, which gives them an appropriate base for learning academic and cognitive skills (Goldsmith, 2007). A study published by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2000) found that children’s relationships with their teachers in the early grades impacted how students viewed their school experience through eighth grade. This is particularly true of children who have poor relationships with their parents (Macklem, 2010). Promising Approaches for Improved Results Teachers can and should play a vital role in teaching and coaching children through learning and using strategies to help with emotional regulation (RimmKauffman et al., 2009). Children are able to learn to control their emotional reactions by using the prefrontal cortex (Macklem, 2010). An emotional reaction can be reversed through practice and training when the prefrontal cortex is able to override the initial response within the amygdala. Children who would otherwise react to stimuli with fear or aggression are able to use their prefrontal cortex to react calmly and effectively. If a child’s prefrontal cortex is activated during a stressful situation the child is more likely to recover quickly from negative emotions and stress. Once teachers understand their role in helping children gain control over their emotional regulation they are able to begin making steps within their classroom to help their students succeed. Teachers need to have an understanding of the importance of labeling and discussing emotions, knowing how to react to temper tantrums, and need to have a variety of classroom-friendly cognitive behavioral therapy practices that can be used to teach strategies. Research shows it is essential these strategies are taught and practiced in the child’s main classroom (Macklem, 2010). When emotional regulation strategies are taught in the classroom students are more likely to show improved behavioral control, peer social skills, and a decrease in withdrawn or off-task behaviors (Wyman et al., 2010). LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 161 Ann-Bailey Lipsett Discussing Emotions in the Classroom Teachers can facilitate a child’s understanding and control of one’s emotions simply by helping children label their emotions, identify what makes them angry, and learn strategies they can use when they experience particular emotions. By teaching children to label and identify emotions and emotional strategies teachers are able to help children respond to environmental stimuli with their prefrontal cortex instead of their amygdala. This gives children the ability to override the automatic fearful responses developed in the amygdala, leading to a decreased reaction time. One technique that teachers can use to facilitate discussions about emotions is people watching (Macklem, 2010). Observing others from a distance or even watching sitcoms and labeling people’s emotions can help children to identify different emotions and emotional reactions. Discussing why people react in different ways and determining whether or not their reactions are positive or negative will open the door to conversations about how a child can identify and regulate his or her own emotions. This will also help children begin to take other people’s perspectives. Classroom teachers should frequently identify their own emotions, the emotions of characters in books, as well as help children identify their own emotions. By teaching “feeling” words and using them regularly teachers are able to give children the language they need to begin to own their emotions, allowing their prefrontal cortex to override their amygdala. Once children are able to identify their own emotions as angry or happy they can begin listing what causes them to experience these emotions. This allows children to become increasingly self-aware of how they interact in their own environment. Once children are able to identify their own emotions as well as events that lead to these emotions they are ready to begin learning coping strategies. Helping a child to distinguish between the emotion and the action will begin to help the child feel control over his or her emotions. Children need to understand that it is alright to be angry when a friend takes their toy but that it is not alright to hit (Macklem, 2010). Teachers can identify problem-solving strategies to help children determine the best course of action once they feel angry. Creating prompt cards with these strategies on them, as well as rehearsing the strategies, will give children specific replacement behaviors for the negative actions, and will also aid their understanding of how they can control their actions and emotions. These strategies tie in the role of the hippocampus, creating memories the child can rely on in order to react to environmental stimuli. 162 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Children also benefit from learning their own physical symptoms that are associated with their emotions. For instance, they may need direct instruction on how their body becomes tense when they are angry or how they have difficulty concentrating when they are worried. This can be done in correlation with intensity charting (Macklem, 2010). Reacting to Strong Emotions in the School Environment Children without strongly developed emotional regulation are more likely to act out in the classroom. Teachers need to understand the causes of the actingout behavior as well as ways they can interact with the child to promote emotional regulating strategies (Crowe, 2009). A frequent strategy used by teachers is time-out, where a child is placed in a chair in the back of the room or in the hallway away from stimulation and the class. This strategy is often beneficial for the teacher and the other students, but sends a message of rejection to the child in time-out. In situations where a child with high anxiety and poor emotional regulation is placed in time-out away from anyone to help him or her regulate emotions, the child is likely to feel overwhelmed and frustrated (Goldsmith, 2007). This can lead to violent and destructive behavior. Instead of using time-out, teachers can utilize a time-in approach where they place the children in closer proximity to them. This allows the child to feel the adult’s presence when he or she is calming down, aiding in his or her regulation. In the classroom this can be done by placing a chair closer to the teacher in the front of the room, yet slightly off to the side so that the child feels the teacher’s presence but is not the center of attention. How a teacher talks to children during times of heightened emotions is critical. A teacher who uses distraction techniques (“Here’s a sticker!”) will manage the behavior in the short term but will not help the child regulate emotions in the future. Instead a teacher can use language that promotes self-regulating such as, “It’s time to calm down. You can think of something else” (Goldsmith, 2007). A teacher can also use problem-solving language such as, “Ask him if you can use it when you are finished.” When a child is upset it is essential to match a teacher’s reaction with the child’s temperament. Punishing overly anxious children in a punitive manner will only lead to further exciting them, and will not aid the student in calming down (Kagan & Snidman, 2004). For particularly anxious children it is important not to push them into situations where they do not feel comfortable—and equally important not to protect them from those same situations (Macklem, 2010). Instead a teacher can scaffold the LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 163 Ann-Bailey Lipsett child’s exposure to the situation, allowing the student to know the teacher is there to support him or her, but that it is the child’s job to manage the situation. Highly anxious children will react best when they are in new situations where they feel safe yet are encouraged to take risks. Teachers conferencing one on one with an upset child need to use eyeto-eye techniques along with simple, non-threatening language (Goldsmith, 2007). They should acknowledge the child’s emotion and offer strategies while maintaining a respectful physical distance. During this time teachers should monitor their body language, how they vary their facial expressions, and their tone of voice (Kauffman et al., 2006). Their conversations should be absent of judgment of the child and the behavior but instead should describe the behavior and end with briefly summarizing the conversation for the child (Crowe, 2009). Reaching Abagia: Applying Emotional Regulation Teaching Practices In hopes of giving Abagia strategies to regulate her own emotions, I formed a morning social skills group. Seven children in three different kindergarten classrooms were identified as needing emotional regulation strategies. Although research shows that interventions are best conducted in the child’s main classroom, due to the academic demands and scheduling conflicts this was not possible at this time. Each teacher filled out a questionnaire on how the child reacted when upset, how frequently the child became upset, how long it took the child to return to task after being upset, and the type of language the child used when upset (Appendix A). Each teacher also identified a goal he or she would like to see the child accomplish. For five of the students teachers noted that they would like the child to use words or phrases to express emotions instead of grunting or pushing other children, while two were given goals to react to situations with the appropriate emotion. The children attended a half-hour small-group session every morning for three weeks. Each session began with a brief morning meeting following the structure recommended by Responsive Classroom in order to build community and trust among the group members (Kriete, 2002). The morning meetings consisted of the children sitting in a circle, taking turns greeting one another using appropriate eye contact and language. Following the structured greeting group rapport was built through giving each student an opportunity to share something he or she was 164 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation excited about or to answer a question of the day. The meeting ended with a short activity or game designed to help the children feel comfortable and have fun with their group members. After the morning meeting the group transitioned to the planned focus activity for the day. The first week students created a common language by labeling emotions of characters in books, animal pictures (from The Blue Day Book for Kids, Grieve, 2005), and in themselves. They also worked to identify emotional triggers and distinguished between different degrees of emotions (e.g., a little sad, really sad, a little angry, really angry) while reading Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day (Voirst, 1972). The students modeled emotional reactions for one another and labeled each emotion. I spent time with the classroom teachers to make sure they understood the language that was being used in the small group so that it could be carried over into the classroom. I also spent time in each classroom throughout the day to apply the same language from the group to situations that arose in the classroom. Once the group was able to label emotions we turned our focus toward how to react with appropriate emotional responses to situations. It had been noted that one of the students hit herself when angry, whether or not it was because she lost a crayon or she made a mistake on a paper. The group spent time each morning practicing tension-relieving practices such as tensing and relaxing arm muscles, doing wall pushups, and letting out deep breaths of air as though blowing bubbles. The group developed its own language for these activities so that the children were able to be prompted easily to apply these strategies when upset. The group read the book Chicken Little (Emberley & Emberley, 2010) and created a hierarchy of emotions from “the sky is falling” to “it is a beautiful day” (Macklem, 2010). The following day the group listed a range of activities that cause them to have emotions (playing with friends, not having anyone to play with at recess, losing a crayon, a hurt toe, an angry mother) and applied these reactions to the hierarchy chart in order to identify the appropriate emotions for each situation. (The group unanimously felt that having an angry mother was far worse than a hurt toe or sitting out at recess.) These exercises were intended to strengthen the connection between the amygdala’s perception of environmental stressors and the prefrontal cortex’s ability to control the reaction to the stressor. Close communication with the classroom teachers continued, as well as opportunities to carry over the language used in the small-group setting into the classroom. In the third week the students role-played situations they viewed as stressful in order to practice using appropriate words and phrases in their emotional reactions. LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 165 Ann-Bailey Lipsett They were then given tasks that would allow them to practice using these strategies (e.g., they were given difficult puzzles so that they could practice what to do when work seems too hard and were given a game where the teacher won so they could practice what to do when they lost a game). By practicing these situations it is hoped they developed both a memory in their hippocampus of what to do in a similar situation, as well as a plan in their pre-frontal cortex that would help override any immediate reaction their amygdala would otherwise signal. During this project I found that in order to have a long-term impact on students’ ability to regulate their emotions the focus must be not only on the students themselves but also on the communication between me and the classroom teacher.­ Educating the classroom teachers about the importance of teaching emotional regulating strategies, how to support these strategies in the classroom, and how to respond to difficult behaviors most likely will have a greater impact on the students than the small-group intervention itself. This communication was supported through frequent e-mails between the group leader and classroom teachers, opportunities to model language and strategies for the teachers, an informational packet explaining how to support emotional regulation in the classroom (Appendix B). In the future I would like to create voice threads with the students in order to increase this common language across settings. The voice threads would be developed during the sessions and posted onto the school’s on-line student newspaper for both parents and classroom teachers to view so that all adults who work with the children would be on the same page. Typically, when children publish voice threads they are excited to share their video projects with their teachers, peers, and parents. This ensures that their parents and teachers hear the language that had been introduced and would be able to coach their children in emotional situations to react appropriately. Due to scheduling conflicts and end-of-year testing we were unable to publish the voice threads we created this year. Results Anecdotal records show that all seven students appeared to increase their use of language in regards to emotions and were able to give examples of appropriate reactions for particular situations. However, whether or not they will continue to use this language once the group is no longer meeting is currently unknown as this group was conducted toward the end of the school year. In her classroom I observed Abagia becoming upset and then stopping herself, looking around the room for me, verbally labeling the strategies she needed to use, applying them, and moving 166 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation on. She began seeking me out throughout her day to tell me when she used these strategies in the classroom. Although there were certainly times when her frustration got the best of her, the fact that she now has the language to express how she feels and the understanding that she can control her emotions and her environment is essential as the first steps in building her ability to regulate her emotions independently. Continued coaching as well as praise for when she uses these strategies will help her continue to make progress in regulating her own emotions. Other children in the group began to use simple words or gestures to express frustration instead of grabbing toys from other students, or withdrawing from peers. One girl in particular became especially savvy at naming her emotions and would tell her teachers that it was a “move to Australia day” when upset. In the future I would like to repeat this small-group intervention again using a more formal data collection process that would note spontaneous emotionalregulation language use in the classroom before and after the intervention. Next year I hope to increase communication between classroom teachers and parents through voice thread and on-line publishing. Appendix A Date: Student Name: Teacher Name: 1. Is the child able to identify emotions of herself/himself or others? I.e.: Uses the language, “happy, sad, angry, mad” when looking at characters in books, or when talking about self. a. b. c. d. e. Not that I have observed Yes, but only about characters in books, not about peers or self Yes, about peers or characters in books, not about self Yes, when discussing self, characters, and peers Only when discussing self 2. On estimate, how many times a day does the child become emotionally upset? a. b. c. d. 0 1-2 3-5 6+ LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 167 Ann-Bailey Lipsett 3. How does the child react when upset? a. Uses loud grunts or one-word phrases instead of language (i.e., “HEY” instead of “Excuse me, I was using that crayon”) b. Withdraws from the group c. Cries d. Seeks adult attention e. Other (please explain): 4. When you conference with the child is he/she able to use language to explain why he/she is upset? (i.e., “I am sad because Jason will not sit beside me) a. Yes b. No If Yes, from your perspective is the child able to correctly identify what made him/her upset? (i.e., did Jason really not sit beside him/her, or did something else cause the child to become upset?) a. Yes b. No 5. Do the child’s emotional reactions seem age appropriate and match the situation? a. Yes b. No If no, please give an example: 6. How long does it typically take for the child to return to work after becoming upset? a. b. c. d. Returns immediately after adult redirection 2-3 minutes 5 minutes Other (please explain): 7. Is there any other information you would like me to know about the child’s emotional reactions to stress? 8. What would you like to see the child gain from small-group intervention on emotional regulation? 168 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Appendix B Teacher Information Packet Theory and practice behind small-group emotional regulation intervention Emotional Regulation Emotional regulation can be defined as how people: • • • control which emotions they experience how and when they feel emotions how they express emotions, both consciously and subconsciously Emotional regulation determines how a person expresses emotions, navigates through the day, what stimulus he/she will attend to, how one interprets a situation, and how one responds to a situation. In academic settings poor emotional regulation can affect a child’s ability to: • • • • Learn and retain information Interact with peers and adults Begin and complete tasks Focus on task at hand In the classroom this behavior manifests itself in: • • • Impulsive behavior Procrastination Difficulty with flexible thinking (Macklem, 2010) LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 169 Ann-Bailey Lipsett Neurological Background Table 1 Three Regions of the Brain Play a Role in How Emotion Is Processed • • Amygdala • Hippocampus • • • Prefrontal cortex • • • • • Responds when perceives stimulation as a threat Triggers automatic response of increased heart rate and blood pressure Triggers automatic behavioral response based on previous experiences (conditioned response) Triggers a memory system response, telling the amygdala to react based on previously taught knowledge Determines reaction based on past associations stored in child’s memory Context-dependent emotional learning Controls emotional recovery time Can override or inhibit amygdala response to stimuli Anticipates future outcomes to plan emotional responses Training and practice gives logical response to stimuli as opposed to biological response Key factor in self-control and self-regulation Emotional Regulation and the Classroom Early childhood teachers and parents play the greatest impact on a child’s development of emotional regulation due to the large amount of time they spend with the child as caretakers. Research has shown that primary teachers’ relationships with their students have a lasting impact on how children interpret school situations through the eighth grade (Macklem, 2010). This is particularly true of children who have poor relationships with their parents. Children who experience a trusting relationship with a teacher in the early years are more likely to engage freely in exploration, which gives them an appropriate base for learning academic and cognitive skills (Goldsmith, 2007). Teachers can promote positive emotional regulation simply by talking about emotions, labeling emotions, discussing and modeling strategies for coping with these emotions (Macklem, 2010). 170 LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Strategies Labeling Emotions Teaching children to label emotions, both the emotions of others as well as themselves, gives them language to use when processing emotional responses to stimuli. • Use a common language when discussing emotions. • Encourage children to label emotions as a way to understand their role in reacting to the environment. • Observe and discuss the emotional reactions of others. Discuss why people react in different ways and whether or not these reactions are positive or negative. • Identify your own emotions, the emotions of characters in books, and the emotions of the children in the classroom. • Identify the stimulus that leads to an emotion. • Identify and discuss physical reactions in children when they experience a particular emotion (tightened muscles, difficulty concentrating, and diffi­ culty making eye contact) so that they become aware of their own biological responses to stimuli. • Create a hierarchy of emotions and discuss and label the difference between being a little upset and really upset, or a little angry and really angry. • Identify, model, and role-play appropriate reactions to stimulation. Reacting to Strong Emotions in the Classroom How teachers respond to children’s behavior caused by poor emotional regulation has the ability to help or harm a child in the long term. Early childhood teachers have a significant impact on how children learn to regulate their emotions due to the time teachers spend with their students. LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 171 Ann-Bailey Lipsett Table 2 Strategies for Dealing With Child’s Behavior 172 Avoid… Try… Time-out: Time-out sends a message of rejection to the child. Children with high anxiety and poor emotional regulation will feel overwhelmed and frustrated in a time-out setting. This can lead to violent and destructive behavior. Time-in: Placing the child in proximity to the adult. The child is able to feel the adult’s presence, which helps the child calm down and aids his or her self-regulation (Goldsmith, 2007). Distraction techniques: Offering children a sticker when they are upset, or encouraging them to play with something else helps them in the short term but does not aid their ability to calm down on their own in the future. Language that promotes self-regulation: When a child is upset use simple, direct language such as, “It is time to calm down.” “Think of something else,” “Ask him if you can use it when you are finished” (Goldsmith, 2007). Punitive punishment for overly anxious children: Punitively punishing overly anxious children will further excite them, making it more difficult for them to calm down or learn to regulate their emotions in the future (Kagan, 2004). Match your reaction with the child’s temperament: Use non-threatening simple language, your physical presence, eye-to-eye techniques, to help a child become calm (Goldsmith, 2007). Acknowledge child’s emotion, offer strategies while maintaining a respectful distance. Monitor your own body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions (Kauffman, 2006). Banning a particular behavior: While our job is to keep children safe, simply telling them that they are not allowed to hit themselves when upset, kick a chair, or throw a pencil will not help them regulate this behavior in the future. Offer replacement behaviors: Explain to the child that he or she may tighten and release his/her muscles when he/ she feels angry, do wall pushups, or deep breathing exercises. These strategies should be taught when the child is calm and reasonable, and practiced frequently using simple language so when the child is upset the teacher may prompt him/ her with a one- or two-word phrase as a reminder. LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Table 3 Matching Adult Response to Child’s Behavior* Child’s Behavior Pre-tantrum Frowning, sighing, pulling away, fussing Adult’s Response Respond with suggestions, label the feelings, explain the cause of the feelings, offer problem-solving strategies. Whining, complaining, demanding Take a break, go for a walk with the child, encourage talking (just listen), offer to help find a solution, give an explanation, offer help. Irritable, agitated Give choices, give close attention, help to relax if allowed, validate feelings, offer your help. Tantrum Arguing, yelling Stay calm, speak very softly if at all, remind you are nearby and understand why the child is upset, indicate you are standing by to help. Kicking, throwing Post-tantrum Crying Move away, out of sight if possible but make sure the child is safe, remain calm. Help to relax, give positive assurance. Sad Support and reassure, remind the child that he or she can try again. Seeking out support Help to save face, offer options, begin problem solving, talk about how to make things better and how to deal with the emotions in the future. *Table taken from the Practitioner’s Guide to Emotional Regulation in School-Aged Children (Macklem, 2010, p. 56). LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 173 Ann-Bailey Lipsett Note that the use of language with the child is mainly used in the pre-tantrum and post-tantrum stages. As the child’s behavior escalates limit your use of language while maintaining your physical presence. Rationalizing behaviors, exploring choices and problem-solving strategies can be done before and after a tantrum. If a child is in the midst of a tantrum excessive language may further stimulate the child and will not help the child become calm. References Bulotsky-Shearer, R., Dominguez, X., Bell, E., Rouse, H, & Fantuzo, J. (2010). Relations between behavior problems in classroom social and learning situations and peer social competence in Head Start and kindergarten. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(4), 194–210. Crowe, C. (2009). Solving thorny behavior problems: How teachers and students can work together. Turner Falls, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children, Inc. Dearing, E. (2010). The practical implications of scientific evidence linking home learning environments and children’s life chances. PowerPoint slides presented at the Learning and Brain Conference, November, 2010, Boston. Emberley, R., & Emberley, E. (2010). Chicken little. New York: Macmillan Publishing. Gazzaniga, M., Ivry, R., & Mangun, G. (2009). Cognitive neuroscience: The biology of the mind. Third edition. New York: Norton & Company, Inc. Goldsmith, D. (2007). Challenging children’s negative internal working models: Utilizing attachment-based treatment strategies in a therapeutic preschool. Attachment theory in clinical work with children. New York: Guilford Press. Grieve, B. T. (2005). The blue day book for kids. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McNeal Publishing. Kagan, J., & Snidman, N. (2004). The long shadow of temperament. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University. 174 Kauffman, J. (2005). Characteristics of emotional and behavioral disorders of children and youth. New Jersey: Pearson. Kauffman, J., Mostert, M., Trent, S., & Pullen, P. (2006). Managing classroom behavior: A reflective case-based approach. Boston: Pearson Publishing. Kriete, R. (2002). Morning meeting book. Turner Falls, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children, Inc. Macklem, G. (2010). Practitioner’s guide to emotional regulation in school-age children. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 225–266. Rimm-Kauffman, S., Curby, T., Grimm, K., Nathanson, L., & Brock, L. (2009). The contribution of children’s self-regulation and classroom quality to children’s adaptive behaviors in the kindergarten classroom. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 958–972. Voirst, J. (1972). Alexander and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day. New York: Simon and Schuster. Wyman, P., Cross, W., Brown, H., Yu, Q., Tu, X., & Eberly, S. (2010). Intervention to strengthen­ emotional regulation in children with emerging mental health problems: Proximal impact on school behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(5), 707–720. LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 Supporting Emotional Regulation in Elementary School: Brain-Based Strategies and Classroom Interventions to Promote Self-Regulation Ann-Bailey Lipsett is in her ninth year of teaching at a diverse Title One school in Fairfax County, Virginia outside of Washington, DC. She currently teaches a non-categorical special education class for kindergarten and first graders, and has previously taught kindergarten and first grade special education in a full inclusion setting, as well as general education first grade. She has a Bachelor’s degree from Washington and Lee University, a Masters in Special Education from the Univer­ sity of Virginia and is a Special Education Doctoral Student at George Washington University. LEARNing Landscapes | Vol. 5, No. 1, Autumn 2011 175