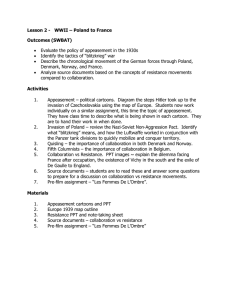

Resistance from the Right: Francois de la Rocque and

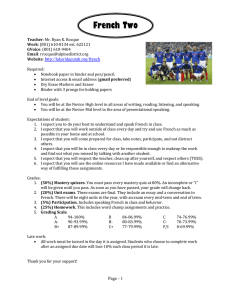

advertisement