Lockerbie verdict

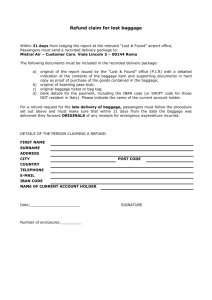

advertisement