Best Practices in Electric Utility Integrated Resource Planning

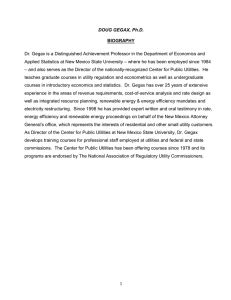

advertisement