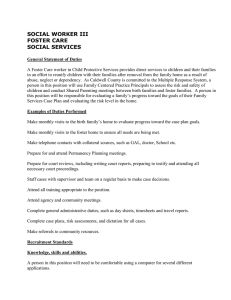

Reasonable Efforts

advertisement