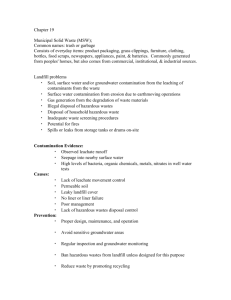

Waste management in Western Australia

advertisement