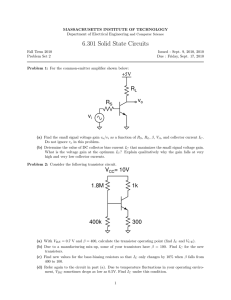

Equation - Electrical and Computer Engineering

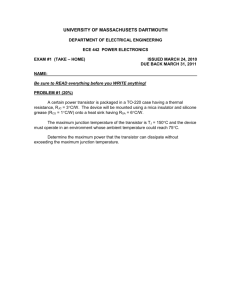

advertisement