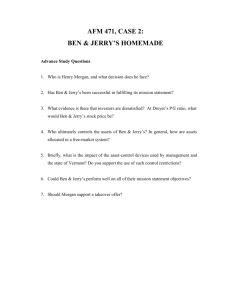

Corporate Social Responsibility

advertisement