here - Kounkuey Design Initiative

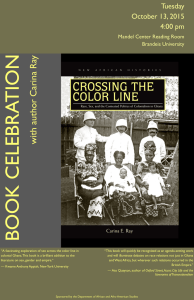

advertisement