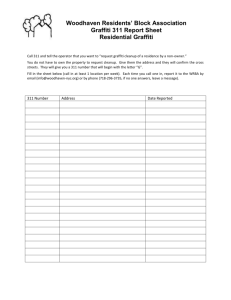

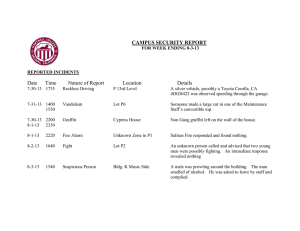

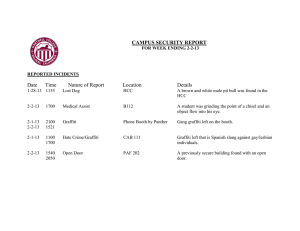

d2.1 graffiti vandalism in public areas and transport

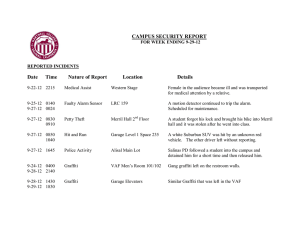

advertisement