Reference Document Reference Document

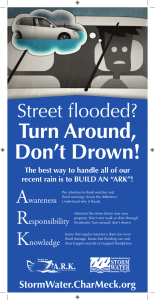

advertisement