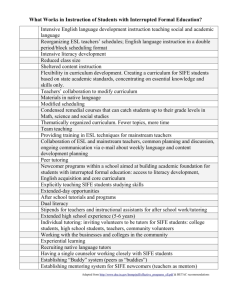

Students with Interrupted Formal Education

advertisement