Study on the impact of Leonardo da Vinci partnerships

Kansainvälisen liikkuvuuden ja yhteistyön keskus

Centret för internationell mobilitet och internationellt samarbete

Centre for International Mobility

Study on the impact of

Leonardo da Vinci partnerships

PARTNERSHIPS 2008–2010

1/2013 FACTS AND FIGURES -REPORT

Translated by Maarit Ritvanen

ISBN 978-951-805-550-4 (pdf)

ISSN 1798-3630

1/2013

Centre for International Mobility CIMO

Contents

1. Introduction

2. How the study was conducted

3. Results

3.1. General

3.2. Aims of projects

3.3. Implementation of projects

3.4. End products of projects

3.5. Dissemination and information

3.6. Impact of projects during their implementation phase

3.6.1. Impact of projects on organisations

12

13

Impact of projects on training and competences in organisations

Impact of projects on international dimension in organisations

Other types of impact on organisations

3.6.2. Impact of projects on teachers and other staff members

Impact of projects on the work and skills of teachers and other staff members

Impact of projects on the international work of teachers and other staff members

3.6.3. Impact of projects on students 22

Impact of projects on the vocational skills of students

Impact of projects on the international competences of students

3.6.4. Impact of projects on local communities

3.7. Impact of projects after their completion

4. Conclusions

4.1. Factors contributing to impact

4.2. Recommendations for further studying

5. Sources

6. Annexes

18

27

29

31

33

35

36

37

Annex 1. Questionnaire used in the impact survey conducted among Finnish partnerships that started during 2008–2010

Annex 2. Leonardo da Vinci partnership projects in Finland between 2008–2012

37

42

8

10

11

12

8

8

4

7

1. Introduction

Leonardo da Vinci, the European Union’s programme for vocational training, supports development of vocational training, European cooperation and mobility of students and staff in the participating organisations. The programme provides funding for mobility and partnership projects, as well as projects for development and transfer of innovation. Important aims of the programme are:

to improve the quality of vocational training practices and to transfer them from country

to country

to improve cooperation between organisations providing vocational education and training

in Europe

to improve the quality and to increase the volume of international mobility of students and

staff

to improve the transparency and recognition of qualifications and competences

to encourage learning of foreign languages and to support the development of ICT-based

contents, pedagogies and practices.

In Finland, 246 applications were submitted in the 2011 call for proposals 1 of the Leonardo programme. The total amount of funding applied for was about 9.96 million euros.

The number of supported projects was 131, meaning that about 53% of applications were approved. The total amount of funding awarded was just over 4.18 million euros. The project types approved in 2011 included 6 transfer of innovation projects, 24 partnerships and 55 mobility projects. The projects include mobility of over 2,400 students, trainees, teachers and other vocational training professionals.

Leonardo Partnerships, with a duration of two years, support comparison of good practices between different countries, establishment of networks, and cooperation and networking of teachers and students among other things. The projects offer those involved in vocational training a chance to learn about training provision in other European countries while focusing on a concrete theme to develop. A partnership should include at least 3 partners from 3 different countries. One of the partners acts as the coordinator of the partnership.

1 At the time of conducting the study, this information was not yet available for the 2012 call for proposals.

Leonardo partnerships are a relatively new action in the programme; funding has been available only from 2008. In Finland, the Leonardo programme is managed by the Centre for

International Mobility CIMO. More information about the different Leonardo actions and their main features are available on CIMO’s website at www.cimo.fi/leonardo.

The partnership projects have proved very popular in Finland and the number of applications has remained high through the years. In 2012, a total of 91 partnership applications were received: 14 of these were by Finnish coordinators and 77 by Finnish partner organisations.

Funding was awarded to 36 projects. The rate of approved projects (40%) was slightly higher than the year before (30 %). The approval rate of partnerships has varied between 31–51%.

The partnerships are popular because compared to other Leonardo actions, the application procedure is easy, administration lighter and they are more flexible.

Projects with Finnish partners have on average 7 to 8 partner organisations. Most partners come from Germany and the United Kingdom. However, the distribution of partners across

Europe has been even. Finnish organisations mostly participate as partners in projects. The rate of Finnish coordinators in projects has increased every year, however. In 2012, there were already 9 Finnish coordinators in approved projects.

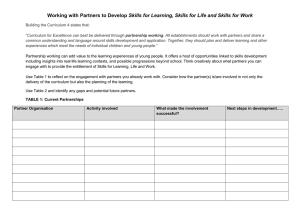

Applications

Coordinators

Partners

Total

Coordinators

Partners

Total

Approved projects

2008

9

53

62

2009

11

66

77

2010

10

74

84

2008

5

27

32

2009

3

36

39

2010

3

23

26

2011

13

67

80

2011

4

20

24

2012

14

77

91

2012

9

27

36

Total

57

337

394

Total

24

133

157

Approval rate

Coordinators + partners

2008

52 %

2009

51 %

2010

31 %

2011

30 %

2012

40 %

Table 1.

Submitted and approved Leonardo partnership applications in Finland 2008–2012

Average

40 %

Partnerships make up about 10% of the total budget of the Leonardo programme, making them a relatively small action. In Finland, a total of 157 partnerships were supported during

2008–2012. The amount of funding depends on the country and the volume of mobility.

€

000 €

10 000 €

1 000 €

2008

1

19

1 000 € 8

Total (number) 2

Total € 0 000 €

€

000 €

11 000 €

1 000 €

20 000 €

2009

2

2

2010

1

2

1

2011

0

2012

1

Total

7

9

9

2

12

2

12

17

12 000 € 2 000 € 02 000 € 000 € 2 0 000 €

Table 2.

The number of approved partnerships and their budgets 2008−2012 2

Nowadays, the different sectors of education and training are evenly represented in approved partnerships. The social sciences, business and administration have been the most popular sectors. During the first two years, education sciences featured high, too. During the 2010 call for proposals natural resources and the environment and in 2011 social services, health and sport were also popular.

The purpose of this study is to look into the long-term impact and significance of Leonardo partnerships of Finnish organisations. This kind of study about the impact of partnerships has not been done before. The study includes all partnerships with Finnish partner organisations that started between 2008–2010, a total of 97 partnerships. All of the projects included in the study have finished and the last of them submitted their final reports in the autumn of 2012.

The aim was to find out what the impact had been like and what the partnerships had had an impact on. A survey was conducted as part of the study to ask participating organisations what significance and impact they thought their projects had had on their organisation and its practices and on other organisations. Another aim was to study how to help projects make an impact and to identify good examples and practices in partnerships.

2 The amounts of funding awarded in 2008 were different from those awarded between 2009–2012.

2. How the study was conducted

This study was carried out by collecting information from the final reports submitted by partnership projects that had ended by 2012 and from CIMO’s evaluations of the final reports.

Furthermore, a questionnaire was sent to the contact people of the projects (annex 1) during

October and November 2012 in which were asked them to evaluate what significance and impact their partnership had had on their own organisation and on others. A total of 40 representatives of partnership organisations answered to the questionnaire: 8 of them were from projects that began in 2008, 16 in 2009, and 16 in 2010. Because some of the contact people no longer worked in the original organisations, it was sometimes difficult to get replies. Some of the organisations also only provided answers about one project, even though they had participated in several partnerships. Some of the organisations that took part in the survey were further interviewed on the phone in December 2012 in order to clarify their answers and study the impact further. Annex 2 lists all partnerships funded in Finland between 2008–2012.

7

. Results

3.1. General

Just over half of those who took part in the survey said that their project related to a wider context in their organisation, such as a strategy. In line with the aims of the

Leonardo programme, projects related to development of training and international dimension.

The most common aims of projects were

to develop mobility and its quality

to maintain and develop an international partner network

to exchange information and experiences

to develop the skills of staff

to learn new practices.

Partnerships are seen as an easy tool for development. The administration of projects is relatively light, both students and teachers and other staff can participate, and they provide an easy way to get to know partner organisations. However, the popularity of partnerships makes it quite difficult to get your application approved. A good idea and a careful plan are not guarantees for getting an application approved because the standard of projects is so high. On the other hand, the hard competition ensures that applicants make careful plans and that the quality of projects remains high.

3.2. Aims of projects

Development of joint curricula, courses and concepts and strengthening of links between training institutions and employers were the most common themes in approved projects.

Other popular themes included testing and adoption of common European methods, special needs, quality and evaluation of guidance, improvement of skills of teachers and guidance counsellors, and updating vocational training provision to meet the current skills requirements of employers.

The aim of partnerships was usually to develop international and multicultural dimensions of the participating organisations through the international cooperation in the project and the networks established. Development of international cooperation, in particular, was an

8

important aim for organisations. Organisations wanted to maintain and expand their international partner network through the projects, to strengthen cooperation with partners, and to find new partners to carry out international mobility, for example.

Another common aim was exchange of expertise between vocational training institutions and other organisations. To learn about vocational training curricula, structures and practices in other countries were also often mentioned. By comparing different practices and by developing new things, participants wanted to bring innovation and improve the quality of training in vocational training institutions. Drawing on the experiences gained, participants wanted to develop, for example, new materials, new training modules and methods for different sectors.

Participants hoped that projects would help training institutions better meet the demands of the international labour market and that they would make it easier for students to enter the

European labour market.

Thirdly, motivating young people to take up vocational training and improving the completion rate of training were also common aims.

Other common aims were to improve recognition of studies as well as competences and skills gained during on-the-job training and to develop the ECVET system 3 .

This is good news because according to a study conducted in 2003 4 only a few projects focused on these themes although they are key goals at the EU level.

Improvement of staff, teacher and student mobility was also common in many partnerships.

Participants wanted to spread information about mobility in the Leonardo projects, to increase the volume of mobility and the number of on-the-job training placements, and to improve the quality of mobility, by providing a variety of orientation material and services, for example.

The number of mobilities within partnership projects applied for has increased year by year.

The number of approved mobilities per project in Finland has varied between 400–530. The number of approved mobilities rose considerably in the 2012 call compared to the previous year, and the amount of funding also rose by 152,000 euros from the year before. About 1 /

3 of participants in mobility are students and 2 /

3

are teachers and other staff members. About

3 ECVET is a European credit transfer system for vocational education and training.

4 Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [evaluation of the first phase of the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999–2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase (2000-2006)]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

9

60% of participants are women (62% of students and 58% of staff). More students (about 2 /

3

) than teachers (about 1 /

3

) participate in local activities in projects. Students usually take part in mobility only once whereas teachers and other staff participate on several occasions.

Year

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Applied

875

1 055

1 274

1 280

1 276

Change % applied Approved Change %

approved

21%

21%

0.4%

−0.3%

456

531

396

408

520

Table 3.

Mobilities applied for and approved in partnerships between 2008–2012

16%

−25%

3%

27%

The goal of projects concerned with people with special needs was to acquire information about and to develop services and training for people with special needs, for example, by supporting guidance of students with special needs or learning difficulties, such as deaf students.

Another goal was to provide equal opportunities in international mobility.

3.3. Implementation of projects

According to the final reports and the survey, projects have generally speaking managed to achieve their goals well . According to the survey, projects were the most successful in achieving their goals when it comes to aims relating to project participants, teachers, staff and international goals. According to the final reports, the most common reasons for not achieving one’s goals were lack of human resources, staff changes and some partner organisations not receiving funding. In some cases, projects could not achieve their original goal. For example, methods could not be transferred to Finland as planned because of differences in the education systems.

10

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0% students teachers/stuff those implementing the project other partner organisations

Table 4.

Achievement of goals by target group regional international sectoral others

3.4. End products of projects

Based on the survey and the final reports, the end products of partnership projects related to training and its development or to management and development of processes. The most common concrete end products were:

new training material

surveys about training in certain sectors

sectoral glossaries, and

a variety of publications, such as websites, CDs, reports, brochures, guidebooks or other docu-

ments relating to the theme of the project or about good practices collected during the project.

Participants had also updated processes for training plans, curricula and skills requirements.

It was also common to organise seminars for the partners or for a wider audience around the theme of the project.

Many developed administrative processes for mobility, such as relevant documents. Organisations tried to improve the quality of student mobility, for example, by establishing friendship networks for exchange students, producing handbooks for students going on an on-the-job training placement and orientation courses for students going abroad. In one project, a quesdon’t know not at all badly to some extent well very well

11

tionnaire had been sent to employers to find out if they were prepared to take on international students and assessment practices had been standardised.

According to the survey, products and results developed in projects were in active use after the end of the projects, for example, in teaching and administration. People had also continued to develop them or were planning to develop them further in future projects. Participants had not usually commercialised their products, nor had commercialisation been one of the goals of the partners.

3.5. Dissemination and information

Projects have normally provided information about their products and results to their primary target groups – mainly within their own organisations, to partners and others involved in vocational training and their own vocational sector. Information was provided via email, social media and a variety of publications, seminars and conferences. Sometimes local media was also involved. The end products are often publicly available on the project website, for example. Many participating organisations believed that their products and results could be used in other sectors, too. They believed that they could be more widely used in the future.

3.6. Impact of projects during their implementation phase

The majority of respondents to the survey rated the impact of their finalised project as significant or quite significant during its implementation phase. According to the survey and the final reports, the project products and results had had the biggest impact on those implementing the project, teachers and other staff and the partner organisations . The same observation was made in a previous evaluation of the Leonardo programme 5 . It is important to remember that the concrete aims of projects are very varied.

For example, students are not a direct target group in many projects. The quantitative assessment of impact is difficult and impact can be different for different individuals, so we must not make too sweeping conclusions based on observations made in this study. In the following chapters, we will describe the impact of projects on partnership organisations, teachers and other staff members, students and the local community in more detail.

5 Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [evaluation of the first phase of the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999-2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase (2000-2006)]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

12

36%

8%

20%

36%

Very significant

Significant

Quite significant

Somewhat significant

Table 5.

The impact/significance of projects during their implementation phase

3.6.1. Impact of projects on organisations

Over 50 % of project partners in partnerships were vocational education and training institutions, 17 % were higher education institutions and 12 % different types of associations and non-governmental organisations. Adult education institutions and enterprises each account for about 5 % of applicants and approved project partners. There are very few other types of organisations in projects.

2%

1%

8%

5%

4%

8%

12%

58%

Vocational institution/college - total 91

Association, non-governmental organisation - total 19

University of Applied Sciences (polytechnic) - total 1

University - total 12

Enterprise - total 8

Adult education institution - total

Others - total

Public organisation, public authority - total 2

Research organisation - total 2

Apprenticeship training centre - total 0

Folk high school - total 0

Social partner - total 0

Chamber of commerce - total 0

Table 6.

Approved partnerships 2008−2012 by organisation

1

According to the survey conducted, participants thought that projects had had several positive effects on their organisations and on what they do. On the basis of the survey, many projects appear to have had a lasting impact on training and other practices . End results and products of projects were still being actively used in training and education as well as in administration. Participation in projects increased participants’ knowledge about what was being done in projects, such as training or European practices in their particular sector.

Impact of projects on training and competences in organisations

Most respondents to the survey thought that their project or its products had improved the quality of training in their organisation . They said that, for example, the quality of international work had improved, such as practices, guidance and documents relating to mobility.

The quality of education and training had also improved when it comes to contents and ways of working.

”The project has brought together different points of view about both the management and practices of the organisation. This has led to a common vision about the forms, structure and goals of staff training. This now supports our everyday work better. People participating in the project included not only managers but also those directly responsible for planning of training and the teachers who provide the training in practice. The project has had a direct impact on the volume and quality of cooperation between staff members.”

”During our project we developed the existing descriptions of our practices and made use of ideas and good practices that we got from our partner organisations. The descriptions form a basis for all of our planning of staff training, its implementation and evaluation. Thanks to the project, even new staff members can now easily get the hang of our processes.” 6

Partnerships have had a great impact on training and competences in vocational institutions and other organisations. During their visits to partner organisations, participants often adopted new practices which they then started using and developed further in their own organisations. These included new practical teaching and guidance tools and new teaching materials.

Projects had also led to new teaching modules.

6 The quotes in this study are from the final reports of partnerships and from the survey conducted as part of this study.

1

”We created a “logbook model”, which we used to collect information about different groups, to outline goals for the group, to monitor implementation and to reflect on successes and challenges. The logbook also served as a tool for evaluating and assessing the trainer’s own work. We still use this logbook. Many practical exercises and teaching methods that we shared and developed along the way are also still in use.”

Some projects also studied and developed recognition of competences between vocational education and training and higher education. However, very few concrete results were presented about the ECVET credit transfer system in the final reports. The national situation is very different in different countries and the level of adoption of the system varies greatly, which presented challenges to projects.

Projects assessed how well the credit transfer system worked in the context of the current education and training systems using a few selected qualifications as case studies. Exchanges carried out in projects were used to evaluate how the principles of the transfer system worked in practice. In addition, projects developed and adopted shared tools for teachers to help organisations start using ECVET. Projects also analysed how the credit transfer system could be used in the international mobility of those in vocational training.

”The goal of the project was to:

- find out how each partner country could adopt the European credit transfer system for vocational

training ECVET

- find out which strengths each country has relating to adoption of the system and how their own

education and qualification systems support the adoption of ECVET

- carry out a SWOT analysis

- establish a permanent mobility network between the partner countries

- test ECVET in practice with a few case studies

- accomplish a Memorandum of Understanding about the use of ECVET.

We created an Excel tool together to compare qualifications, their contents and skills requirements in three countries. We also designed an ECVET tool for an exchange period, describing the key competences required of a hotel receptionist (part of a qualification in tourism) as tasks/activities/objects of evaluation and as knowledge, skills and competences required. We also established assessment criteria using the three-tier assessment scale used in Finnish qualifications. All this and other joint activities

1

in the project took so much time that we were not yet able to carry out the exchanges of students and test the tools we developed or achieve the development goals set for the exchanges. However, we will complete these within the LAMP mobility project.

There was a clear increase in the knowledge, interest and motivation among participating trainers and other staff members to start using ECVET in practice and testing it with partners from abroad; people became more confident about trying something new. The events organised in the project, the different materials as well as exchange of information and experiences and jointly designed tools have established a good base for future cooperation in the LAMP mobility and other projects. Our understanding about the education and training systems, especially about vocational training, on-the-job training practices and skills assessment in the partner countries has increased considerably. Trust has been established especially between partner organisations in the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland.

The partner meetings and the substantial and varied information package about ECVET with accompanying practical exercises have played a very important role in the increase in knowledge and understanding. A survey about the education and training systems in each country and about other elements supporting or curbing the adoption of ECVET carried out in the beginning of the project was also very illuminating and interesting. According to the survey, Finland is in a very good position to start using ECVET.

AIKE International as a national support organisation for international work in vocational training has acquired important experience and information about ECVET, about education and training systems, vocational training practices in the partner countries etc. The surveys, tools, working methods and results of the project can be used in other sectors and partnerships, too. They can also be adapted to fit your own needs and goals.”

According to the survey and the final reports, the projects have had a surprisingly big impact on the ICT skills of participants. The participation of teachers and other staff members in projects has contributed to increase in ICT competences and use of new methods in organisations. Materials created during projects were normally presented on a website, Moodle,

Facebook or other computer-based systems. Participants found the use of social media in teaching and guidance helpful, for example. They found it a good and motivating additional tool to use along with the more traditional methods of contact and distance teaching.

1

Impact of projects on international dimension in organisations

Organisations had become more international through participation in projects and their interest in international cooperation had often grown . Language and cultural skills were the most common skills developed during participation in projects. Participants learned to communicate and interact better in international situations. Projects had provided organisations with new opportunities and ideas for mobility. Models and practices for mobility that were designed in projects were also used to develop practices in home organisations.

Organisations became better prepared to receive international students and trainees. Some organisations said that the volume of their student mobility had grown considerably thanks to the project. Organisations also acquired new international partners and they often continued working with them even after the end of the project. Organisations had got to know their partners better and they had learned to use their international networks more efficiently. The experience had encouraged some to provide guidance to students with immigrant background, for example.

”Our training provision is going through big changes and we already have adopted environmental and module approaches and the new EQF-based skills requirements from the project. Thanks to the network, we are in a position to review many other Nordic practices which are particularly useful for

Finland.”

Participants said that the willingness of organisations to take part in new projects had increased through partnerships. Participating organisations had naturally also learned more about international project work, particularly in cases when it was the organisation’s first international project. International projects had become part of their regular work in many organisations.

The differences between partner organisations were regarded both as a weakness and strength.

The fact that organisations had expertise in different sectors had made teaching and learning together productive. Due to curricular differences organisations had not necessarily benefited from new professional innovations themselves. Despite this, they still had found it interesting to get to know training institutions in other countries and felt that the chance to share good methods and practices with other partners was a positive experience. Cultural reasons or differences in basic operations of organisations, such as guidance and teaching, sometimes made it more difficult to adapt methods developed in Finnish institutions.

17

”Guidance and teaching in institutions for students with special needs is so specific in Finland that it is not very easy to adopt methods from other European institutions. On the other hand, it is illuminating to see other ways of working and to realise that you can manage and get results in very different ways. We also learned from others: for example, at the stage of competition entries, we realised that we needed to pay even more attention to motivating the students.”

Other types of impact on organisations

In addition to international cooperation, organisations had increased their cooperation with a variety of other organisations involved in vocational education and training, enterprises and other organisations and stakeholders that had an interest in the theme of the project across different sectors locally, nationally and regionally. Project meetings and intervening activities had raised the team spirit within the participating organisations.

3.6.2. Impact of projects on teachers and other staff members

According to the final reports and the survey, the impact of partnerships on teachers and other staff members of the participating organisations had been clearly more significant than on other people participating in them. This is natural because teachers and other staff members are usually more involved in projects both implementing them and being their target groups. Teachers also often take part on mobilities more than once within a single project whereas students usually only go on an exchange once. On the basis of the final reports, it is not possible to say that any particular individual area would had been affected by the projects more than another when it comes to teachers and staff.

Impact of projects on the work and skills of teachers and other staff members

Teachers and other staff members learned more about their own field of expertise , their practices and teaching in the projects. Working together with other people and the visits offered them opportunities to learn about teaching methods and practices of other organisations in other countries. Comparing curricula in partner organisations allowed them to identify strengths, problems and weaknesses in their own organisations, and they were able to develop teaching and study programmes on the basis of these observations. New ideas could also be used to develop curricula. Projects had expanded teachers’ and other staff members’ knowledge of different working methods and tools as well as issues relating to occupational safety.

18

Some had learned new methods to teach and help students with special needs , which had helped make progress in teaching and training those who worked with them. Students and teachers had, for example, designed together tools to assist students with special needs.

”We learned from our partner how you can and must find out about the needs of deaf disabled people or people with mental health problems and how a therapeutic community may impact the welfare of its residents. We have started staff training with a university psychology department. Our goal is to train our staff to understand the needs and wishes of our clients better and to strengthen the therapeutic community in our units.”

Project: Enhance Mobility for Trainees at Risk of Social Exclusion

Project partner: Axxell

Year: 2009

The aim of the project Enhance Mobility for Trainees at Risk of Social Exclusion was to promote equal opportunities in student mobility. Another aim was to facilitate international mobility among students who were not motivated and to reduce the drop-out rate of students by involving them in mobility. Another goal was to increase the awareness of teachers of obstacles to international mobility in this target group.

The project had a positive impact on the attitudes of both staff and students. Teachers whose students participated in the project observed that the students’ motivation increased significantly and that they became more active in lessons. Participation in projects also helped a few students lacking in motivation to finish their studies. After the project, teachers were less prejudiced and they were more prepared to give students that were less successful in their studies a chance to go on an exchange. Students are no longer selected to take part in

19

exchanges on the basis of their success in their studies but on the basis of how much they would benefit from it. Now students who have been less successful in their studies and lack motivation also participate in mobility.

Cooperation with partners continues with mobility projects. The organisation has participated in other EU projects since the project, too. Exchanges have been carried out through the Nordplus Programme and Leonardo mobility projects. The organisation is also planning a new transfer of innovation project within the Leonardo programme, the aim of which will be to develop a quality control system for preparation of international exchanges for the same target group.

On the basis of the final reports, partnerships have had a big impact on the motivation of teachers and other staff members. Although it had sometimes been difficult to motivate staff to participate in projects due to lack of time, resources, funding or language skills, for example, most of the respondents said that the motivation of participants had improved.

Especially mobility was regarded as a useful means for motivating staff and it also energised participants to improve their work.

Exchanging experiences with colleagues from abroad was regarded as rewarding and interesting. It was inspiring to realise that partners had similar problems to which you could try to find solutions together. Job-shadowing was regarded as very useful because it developed teachers’ professional skills in addition to increasing motivation. Mobilities also helped improve administration of international exchanges and placements, by providing information about students of partner institutions, about their studies and preferences regarding leisure activities and accommodation.

Project participants also learned about challenges involved in student mobility and how students act in international environments. Visits to work places were considered as very useful and rewarding with regard to participants’ own work development.

20

”Generally speaking participants had a positive view of project visits and partnerships, which increases motivation. They could reflect on the benefits of the visits, for example, in relation to their own work, the education system and curricula, teaching and learning methods, guidance of students with special needs, cooperation between employers and training institutions, on-the-job training and work placement practices and the differences and similarities between different countries and among partners.

Knowledge of different cultures and partners increased thanks to visits, team work and conversations. It was an enlightening experience. From the training institutions’ point of view, knowledge of different education and training systems, practices and cooperation between training institutions and employers will make future cooperation, such as visits, new projects and international placements of students, easier.”

As with students, the final reports indicate that the ICT skills of teachers improved as did their use of new learning platforms, such as Moodle, because they had to learn to use new tools during projects as well as use them more frequently, for example, in presentations and communication with partners. The use of new ICT solutions has also aroused interest in other new

ICT tools. The use of social media as a tool had intensified communication between partners compared to using just email, which had contributed to the good results of projects.

”The experiences from the project prove that social media can be useful and beneficial in inter-

national projects:

- An easy-to-use blog is much more suitable for providing information about a project than the tradi-

tional website. All partners can add content to it without needing to have programming skills.

- Wiki works well for editing shared documents, and a wiki page (in this case Google Docs) is a

good place to store shared documents. You no longer need to search for documents from among

dozens of emails and for the different versions from the attachments instead you always have the

latest versions easily at hand.”

Impact of projects on the international work of teachers and other staff members

The final reports demonstrate that projects made teachers and other staff members become more international . Teachers’ attitudes had changed: international relations and projects became a part of their regular work culture instead of being something special. People also learned to understand students from different cultural backgrounds better. Supervision and

21

guidance of international participants also increased teachers’ teaching and organisational skills . Staff also gained a lot of experience of working with people from different work and communication cultures. Respondents said that working in an international context had particularly increased participants’ confidence.

According to the reports and the survey, the language skills of participating teachers and other staff members had also improved, especially of those who had not used their skills for some time.

According to the reports, participation in projects also offered staff a good opportunity to network both within one’s own organisation and with other organisations both in Finland and internationally. Personal contacts established during projects made closer cooperation possible in the future. New contacts and the improved language skills made it easier for students and teachers to find new on-the-job training places abroad. The number of these places also increased.

According to the final reports and the survey, the project know-how of the partner organisations increased. Participants learned to understand better what project cooperation requires and they were better prepared to get involved in projects. Participants became more experienced in coordination, management and implementation of projects, especially those partners and participants who were involved in their first LLP project. The awareness about international mobility and other cooperation opportunities increased, which also aroused interest in them. Organisational and team leadership skills developed, too. Participants’ awareness of

EU policies, instruments and institutions also expanded.

3.6.3. Impact of projects on students

According to the final reports and the survey, students were often not the primary target groups in Leonardo partnerships. The projects’ main focus was often on teaching and development of student mobility with an indirect impact on students . The impact on students came through teachers who had participated in projects and through teaching materials and methods developed.

Improvement of language skills, international experiences and adoption of new working methods were the most common effects on students.

22

Impact of projects on the vocational skills of students

According to the final reports, the increase in vocational skills was the biggest impact on students. In addition to skills and knowledge in their own field of expertise, projects also affected professional development in other ways. Students learned what kind of social skills they need to be able to work and train abroad, and their confidence in the possibility of having an international career increased. Students were often involved in the practical arrangements of the programme of project visits, which gave them good practical project work experience.

Students’ ICT skills also improved and they gained practical experience of using a variety of learning tools. Students had also acquired knowledge about further study opportunities in partner organisations abroad.

According to the final reports, in addition to vocational skills, projects had increased students’ confidence, social skills and motivation. For example, during and after projects, students had been more motivated in participating in additional school activities, such as student councils and representing the school in different events.

Impact of projects on the international competences of students

Partnerships have also had a positive impact on students’ language learning. They became more motivated in studying languages and their vocabulary in their trade increased. Using a foreign language and communicating with students with different cultural backgrounds made students feel more comfortable at working in an international context. This increased their motivation and confidence. Furthermore, respondents said that through participation in projects students had become more open-minded, tolerant and sympathetic towards foreigners. A community feeling among participants increased and their team work skills improved.

The short duration of mobilities in partnerships was regarded as both an advantage and a disadvantage. On one hand, the short duration was criticised for reducing impact but, on the other hand, it made mobilities more accessible. Respondents thought that even short exchange periods made students more likely to consider working abroad in the future. Those students who had taken part in an exchange or placement had benefited from the biggest impact.

Especially social skills, motivation and confidence had increased among those students.

2

Respondents noted that students who had taken part in exchanges were, for example, more open and more willing to express their thoughts and ideas and were more willing to take part in different activities. During mobility periods, students were able to learn about working methods in their own trade in different countries and to network with other young people who will be working in the same trade as them.

Students were selected to participate for various different reasons. Some partner organisations selected students who were already outgoing and active, and there was not necessarily any remarkable development in their vocational and social skills. Participation of weaker students made other students realise that participation was possible to everyone. Participation in exchanges also made these students more motivated in their studies. Partnership projects were also viewed as a safe introduction to international mobility for students who had little or no experience in travelling. Some of the partner organisations only selected students who were at least 18 years of age, who were independent and already had good language skills so that they would be able to get as much as possible out of the international experience.

”Students’ active language skills improved because they had to use English with people who spoke different dialects, had different linguistic backgrounds and competence levels in English. This learning curve became evident in the remarkable increase in the students’ confidence in using and expressing themselves in a foreign language over the project period (2 years). At the same time, we realised that you will not necessarily always manage just with English in all countries and cultural environments but that you have to be able to be flexible and adopt other forms of communication, too, such as gesturing. This further increased participants’ confidence in using a foreign language.

Industrial visits improved participants’ knowledge of their trade, and seeing different work cultures and practices gave new perspectives on one’s trade and studies. For example, seeing the differences in the standard of facilities, machinery and equipment in different work places and colleges enabled students to compare them to those in Finland and reflect on them. Being able to compare the level of the Finnish education and training and on-the-job training systems with that of their partners, or the quality of training or the ways of doing things helped students strengthen their professional identity and gave them ideas about what they could still learn or do better.

Students’ social skills and motivation increased in the heterogeneous teams. During our project trips we could be working with students with special needs, adult students, young people in initial vocational training or vocational students whose level of skills and competences were close to Finnish higher edu-

2

cation. This could present challenges on cooperation but, when successful, could also be very rewarding for students.

Students became more confident when they had to take care of themselves in English and to manage in different situations. They learned more about different countries and cultures during different visits and presentations and working with people with different cultural backgrounds.”

The students did not always realise what impact the projects had had on them and needed help in becoming aware of it. All project results had not yet necessarily been used in practice during the reporting stage. Respondents said that projects and their results also provided a good starting point for development of international activities.

Project: Your Own Company across Borders

Project partner: Jyväskylä Vocational College

Year: 2008

The Your Own Company across Borders partnership is a good example of developing quality of vocational education and training, an international network and on-the-job learning placements. The project contributed to entrepreneurship training and the Junior Achievement - Young

Enterprise (JA-YE) work in the organisation. The aim of the project was international cooperation of vocational institutions in entrepreneurship training and learning by doing following the

Junior Achievement - Young Enterprise model.

Students who participated in the project started a business following the principles of the

JA-YE programme. The job of the businesses was to export their products or services to another participating country in cooperation with the student businesses of that country. The Finnish student businesses exported their products and services to Germany and the Netherlands and in return they hosted the German student businesses. Selling of products and services was realised as student exchanges. Student businesses also conducted a market study and made a business plan. The exchanges lasted for about a week and students were usually accommodated in families. There was a lot of mobility in the project, a total of 37 exchanges although

2

funding was only received for 12. Apart from work experience in their own field of expertise, students also gained valuable work experience from abroad and they were able to compare business cultures in different countries. The Active Adventures JA-YE business that participated in the project received the award for the best JA-YE business idea in 2009.

The theme of the project, entrepreneurship, was also linked to regional strategies. The project increased the Jyväskylä Vocational College’s cooperation with local employers. For example, the college has been involved in marketing products of Finnish and local businesses in annual on-the-job learning events abroad.

The project had a substantial impact on the organisation. It improved entrepreneurship pedagogy and guidance in the college. The project also played an important role in developing

Jyväskylä Vocational College’s international work. The more intensive international cooperation helped the college establish a close-knit international network.

Thanks to the experiences gained in the project, the organisation has taken part in many international JA-YE events as well as annual travel fairs taking place in Germany. Jyväskylä

Vocational College now also has a permanent, active international on-the-job training network with its Dutch partner. Cooperation with the partners has been continued in a new partnership project, Triple Learning Platform. Entrepreneurship is the theme of the new project, too.

Cooperation has also continued in a Leonardo transfer of innovation project. The organisation plans to possibly continue the Triple Learning Platform project through a transfer of innovation project in the future.

2

3.6.4. Impact of projects on local communities

According to the survey and the final reports, the impact of partnerships on local communities has been relatively small compared to other stakeholders. Projects in which the local community, such as local employers, were closely involved in are an exception to this. As we noted above, information about projects is normally targeted at the partner organisations and products and results are not usually commercialised. Partly for this reason results don’t tend to spread more widely.

Many projects, of course, never even aimed at regional impact, as has been noted in a previous programme evaluation 8 . However, projects often seem to have a positive impact on cooperation between vocational training institutions and employers. Local employers providing onthe-job training placements for students have tested and adopted assessment tools developed in projects. Projects have helped employers learn about the international work of the partnership. Marketing of training provision locally also improved. Regional service providers have adopted processes developed for people with special needs.

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Students

Teachers/Staff

International

Sectoral

Others

Those implementing the project

Table 7.

Impact/significance of products and results on different target groups.

don’t know not at all a little somewhat a lot very much

8 Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [evaluation of the first phase of the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999-2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase (2000-2006)]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

27

Project: Mobility in Reality

Project partner: Ikaalinen College of Crafts and Design

Year: 2008

The Mobility in Reality project of the Ikaalinen College of Crafts and Design was realised in cooperation with the local community and it has benefited local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). At the moment, only 1% of young people in vocational training take part in an international exchange in Europe. There are administrative, linguistic and financial reasons for this. Another reason is the lack of participation from the SME sector. This is why the partnership wanted to find ways of increasing mobility without compromising quality. The idea was to share previous experiences, identify obstacles to mobility both with regard to young people and

SMEs, and to develop tools to help intermediary organisations select suitable host employers.

During the project, the partners developed a toolkit for hosting international trainees.

The toolkit includes a diagram about the process of receiving a trainee, describing the whole process and in which stages the other tools developed in the project can be used. It also includes a tool that shows SMEs what benefits they can get from international trainees.

Furthermore, it includes a questionnaire designed to find out if an employer is ready to receive international trainees and criteria to help find the most suitable placement for a trainee.

The project had an external evaluator whose role was regarded as crucial. The evaluator helped the coordinator and partners in different situations and assisted in finding common ground in the project work.

The organisation has continued working on the theme in a project Perfect Match, which is a

Leonardo transfer of innovation project. Products developed in the Mobility in Reality project have been further developed in this project. Another aim is to extend the regional impact.

28

3.7. Impact of projects after their completion

Respondents to the survey considered the long-term impact of partnerships to be significant.

The long-term effects could not be assessed for all projects because we were not able to contact representatives for all of them. The assessment of long-term impact is also difficult because partnerships have only been around since 2008. There are relatively few organisations that would have had experiences of partnerships and of their impact over a long period. In this category we can include projects that started between 2008 and 2009, which amounts to 71 projects. They had some clear long-term effects that demonstrated themselves largely in the same way as was observed in the evaluation of the Leonardo programme commissioned by the

Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture in 2003. Projects had had an impact on training practices of organisations, for example, and improved the quality of vocational training in the partner organisations.

21%

21%

29%

29%

Very significant

Significant

Quite significant

Somewhat significant

Table 8.

Long-term impact/significance of projects at a general level

”Those participating in our project pooled their experiences together and spread them around, which, of course, is the main benefit of the project to others.

The so-called dissemination of best practices relates to the above; practical examples of what we have learned in the project include things like how to demonstrate production to a group of consumers on a visit to a farm or how to harvest leaf vegetables in practice.

The materials produced in the project are still available on the intranet shared by the partner colleges and the European partners and partly also on the public website (www.europea.org) even though the project has ended.

29

The contacts the students made can continue to help them get trainee placements or study places abroad – in almost any European country.

Businesses in the sector in question have got information about training and trainers have listened to the needs of businesses. Both have an impact on teaching.”

The majority of organisations had continued their cooperation with their project partners after the end of the projects . In most cases, cooperation was continued in the context of established networks, international events, mobility and new projects. Transfer of information was also common among partners. Sometimes cooperation had also spread to other units within partner organisations.

Partner organisations had continued their cooperation via student, teacher and staff mobility.

There was also a good deal of unofficial contact. Students had, for example, visited each other.

Organisations clearly regarded projects as useful because just over half of respondents had started new projects or were planning to do so. The final reports also confirmed that planning of new projects was common. Especially those organisations that rated the impact of their project as significant had continued cooperation in another project. According to the final reports, it was easier to start new projects when you had worked together with your partners before.

Respondents to the survey had continued their cooperation in a variety of different programmes, such as partnerships, other Leonardo actions (e.g. transfer of innovation and mobility) or other EU-funded projects (e.g. Youth in Action, Grundtvig, Comenius or EU

Culture) or Nordplus progamme. Some organisations continued to develop the same theme further in their new projects. Some, on the other hand, started working on different themes or sectors or moved on to larger development projects. Some organisations had participated in several projects funded through different programmes. Some would have started a new project but had not received funding or were only just in the process of applying for funding.

Not all organisations had continued their cooperation after the end of the project. This cannot be viewed as a sign that the project or the cooperation had failed, however: organisations had noticed that there was no longer need for the cooperation. Partners being geographically far away from each other, too different or operating in different market areas were listed as reasons for discontinuing cooperation. Some of the active people working on the projects had moved on to different jobs or other sectors.

0

. Conclusions

We can say that a partnership has had a long-term impact if relevant results and products of the project have been used or further developed after the end of the project. Based on this study, it is clear that many of the methods, end results and products developed in partnerships have been used in the partner organisations. They have also been further developed, for example, within new EU projects among the partner organisations after the end of the projects.

The results of this study are to great extent similar to results received in a previous evaluation of the programme 9 – Leonardo da Vinci partnerships have clearly had a positive impact on the partner organisations and their international dimension. This impact has extended beyond the project duration.

Finnish organisations have a very positive view of partnerships and take part actively in them.

From this we can conclude that partnerships provide an efficient tool to develop organisations and to make them more international. We can assume that without the projects and the accompanying funding organisations might not have been able to achieve the results they had.

Through partnerships, organisations have been able to focus on a theme important to them and further develop it. In their final reports, the majority of respondents thought that methods, materials, tools and results developed during projects could be useful to other organisations, too. They could easily be adapted to work in different education and training institutions and organisations.

”The results are available to all on the Caravan website in French and in English, and in Finnish at the website of Sorin Sirkus.

Teachers of both the social circus and the youth circus can benefit from the results when they design new curricula and teaching methods. They can also benefit in the future from the international contacts they have made. Teachers and other people who are new to social circus and are interested in starting to teach this way can benefit from available research and the toolkit.

Employers can benefit from the available information when planning in-service and further training for teachers.

9 Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [evaluation of the first phase of the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999–2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase (2000-2006)]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

1

In the future, the results can be used to develop training for teachers in social circuses both nationally and internationally. There are needs for both short courses and more extensive training.

Based on the results acquired, the Caravan network is planning a new Leonardo project (transfer of innovation) together with universities in Brussels and Paris to design, study and pilot a training module for trainers in social circuses. The new ESF project on social circuses of the University of

Tampere will use results of the project and cooperation with them is continuing.

Sorin Sirkus is a national centre for providing services in and developing youth work appointed by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. Social circus is an important area of development that we want to participate in. We aim to develop knowledge and skills acquired through this project, too, and disseminate it to others. For example, all 4th form pupils in the City of Tampere can visit

Sorin Sirkus and test the new teaching methods themselves.”

Many organisations thought that their project results can also be adapted for use of organisations in different sectors.

”We designed models of staff development for local authorities from five different European countries.

The models have helped us identify good practices and areas for development. The models themselves are continuously being revised but they can help clarify challenges in staff development in the public sector that is going through big changes. The models can never be directly applied in different environments but the basic processes can be adapted to fit different purposes. The good practices in each model can be used as examples and can be of help in many ways. However, there are general and organisation-specific cultural differences which need to be taken into account when the models are applied.

These kinds of differences can relate to power relations, hierarchies and gender equality, for example.

Keeping these in mind, you can apply the project results in different kinds of organisations.”

It is very difficult to quantify the impact of projects, partly because many of the effects relating to teaching and administration, for example, are indirect. Estimates on how many people the end results and products have influenced varied from a few to hundreds. In most cases, respondents to the survey estimated that the projects had influenced directly or indirectly a few dozen people after their completion. The quantitative impact of projects vary greatly depending on the project and the target group. Some of the projects had an impact on quite a small target group, such as students with special needs, or a limited educational sector.

The impact on this specific target group may have been very important, however. Changes of personnel have sometimes made it more difficult to maintain and develop results.

2

4.1. Factors contributing to impact

The final reports of partnerships are very clear about what causes problems in their implementation:

language and communication problems

different work cultures in different countries

differences in partner organisations (e.g. curricular differences)

lack of time and resources

sudden changes in plans, such as dropping out of a partner.

To help with the lack of time and resources, participants wished that there would also be funding available for the administrative work in projects in addition to the mobilities. However, even though the lack of time and resources was very common it was not regarded as insurmountable. To minimise above problems and to facilitate cooperation, partners should pay attention to the below issues:

careful scheduling and sticking to the schedule

steady and committed staff working for the project

being prepared for changes, such as partners not receiving funding or dropping out, for

language and communication problems and lack of time and resources

being prepared to modify the original plan if it turns out that organisations have very

different practices or the original plan was too ambitious

identifying problems on time

To maintain and further develop results achieved and to ensure continuity of cooperation, partners should make sure this does not rely only on a couple of people in their organisations.

”There are a few aspects that should be taken into consideration before starting with such a project:

- Finding the reliable partners is the first and most important step (common needs and goals, common understanding).

- The efforts of all partners are very important.

- It is necessary to assign a coordinator who really understands the structure and the requirements of the project and is able to generate new ideas that are feasible and at the same time motivate the team for action.

- It is not necessary for all the team members to know perfect English. Some members in our project experienced a huge change in their English writing and speaking skills during this project. It is obvious that during the project meetings all thoughts and activities are integrated. The working hours are only theoretical, since during the visit the team spends almost the entire time together talking about various issues, exchanging thoughts, planning future cooperation, discussing common pedagogical problems, etc. The lifecycle of the project relies on the meetings.”

You can tell from the final reports and the challenges identified that it helps projects if partners are very clear about their individual goals from the beginning. Other points that contribute to the success of projects include common goals, ways of working and shared understanding about the substance of the project. Establishment of trust among partners was seen as important and participants thought you should reserve time for it and create facilities and situations that are conducive to it. Participants found that social media had made cooperation closer and easier. They thought that you did not always need a big group of partners but that working with a smaller partnership and a careful plan can be very efficient and effective, too.

As we noted above, projects had had the biggest impact on those people who took part in mobilities. However, participants commented that had the duration been longer the impact of mobilities would have been more significant both on students and teachers and staff. When possible this should be taken into account when planning mobilities.

A wish to be able to have mobilities of bigger groups was also expressed in the interviews.

The current maximum number (24) can be limiting if there are participating students and teachers from a number of different sectors from an organisation. Training institutions should also make better use of the opportunities projects offer for internationalisation at home so that they would have a bigger impact on those people who do not take part in mobilities.

According to earlier Leonardo da Vinci evaluations 10 , selecting a theme that was important and useful for the target group was important with regard to impact. This was noted in the interviews conducted as part of the study. An important and useful theme was

10 Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [evaluation of the first phase of the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999–2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase (2000–2006)]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

regarded more important than apparent innovation. The impact of projects focusing on more general themes had naturally been wider because their results could be used in a variety of sectors and different types of organisations. The type of organisation also seemed to be significant regarding long-term impact. Projects carried out by public organisations have had long-lasting impact, particularly when the coordinator has been a permanent member of staff.

As noted above, information about projects and their results was distributed mainly within the participating organisations, among partners and other relevant bodies within the sector concerned. Communication was sometimes challenging because, for example, partnerships were not always able to get the local media interested. Organisations wished they had some assistance or training in this area. More information about the projects could also mean more impact. Participating organisations could be offered more training on marketing and dissemination of their projects and results. Most projects said that their results were publicly available on the organisation’s own website or a website specifically created for the project. Materials and results were often provided in English or they had been translated, which contributed to international dissemination and impact.

4.2. Recommendations for further studying

It is recommended that the impact of Leonardo partnerships should be studied again later, because only a few organisations in this study had had long-term experiences from partnerships so far. From the projects studied, only those that had started in 2008 clearly had a wider perspective on the long-term impact of their projects.

A later evaluation could study in more detail how the impact of projects could be further strengthened. To get a better picture of impact, the results should be compared with studies made in other countries.

. Sources

The final reports of Leonardo da Vinci partnerships 2008–2012.

European Shared Treasure. EST database. www.europeansharedtreasure.eu

Leonardo da Vinci statistics 2008–2011. The Centre for International Mobility CIMO.

Mahlamäki-Kultanen, Seija: Leonardo da Vinci -ohjelman ensimmäisen vaiheen (1995–1999) arviointi ja toisen vaiheen (2000–2006) väliarviointi [ evaluation of the first phase of the

Leonardo da Vinci Programme (1999-2006) and the interim assessment of the second phase

(2000-2006) ]. The Finnish Ministry of Education 2003.

. Annexes

Annex 1.

Questionnaire used in the impact survey conducted among Finnish partnerships that started during 2008–2010

Background

1. What year did your project start?

2–4. The name of the project.

5. The name and contact details of the respondent.

6. Is the respondent the same as the original coordinator of the project? yes no

7. Was your project linked to a wider context in your organisation? For example, to your

organisation’s strategy or to curricula, staff or regional development plans.

yes no don’t know

8. What wider context did the project relate to?

Aims of the project

9. What were the aims of the project?

Describe the aims of your project briefly relating to the below target groups. those implementing the project students teachers/staff other partner organisations regional international sectoral others

7

10. Evaluate how the aims were achieved per target group on a scale from 1 to 6.

The aims were achieved for the target group in question 1: very well, 2: well,

3: to some extent, 4: badly, 5: not at all, 6: don’t know those implementing the project students teachers/staff other partner organisations regional international sectoral others

Project products and results

11. What were the end products/results of the project for the below target groups.

Please give concrete examples.

those implementing the project students teachers/staff other partner organisations regional international sectoral others, which?

12. Rate the impact/significance of products or results for the different target groups

on a scale from 1 to 6.

Did they have an impact on the target group: 1: very much, 2: a lot, 3: somewhat,

4: a little, 5: not at all, 6: don’t know those implementing the project students teachers/staff other partner organisations regionally/nationally internationally vocational sector others, which?

8

13. How have the products/methods of the project spread/been disseminated?

Describe dissemination for the below organisations.

Within own organisation

Between partner organisations

Outside the partner network

14. Have project products been commercialised? yes no don’t know

15. How have products/results of your project been commercialised?

The impact of project during its implementation phase

16. Did the project have a lasting impact on the training or other practices of

your organisation?

E.g. pedagogy, contents, competences.

yes no don’t know

17. Why not?

18. What kind?

Please give concrete examples.

19. What kind of new skills did the target groups of the project adopt?

20. Did the project or its results improve the quality of the vocational training

in your organisation?

yes, how? no don’t know

9

21. What other types of impact/significance did the project have during its implementation

phase? For example, did your organisation learn something from your partners

in addition to the end products and results?

yes, describe the impact no other impact don’t know

22. Rate the impact/significance of your project at a general level during the implementation

phase.

very significant significant quite significant somewhat significant not at all significant don’t know

Impact after the end of the project

23. How have you used the project products or results and what impact have they had

after the end of the project?

24. Evaluate how the project products or results have had a direct or indirect impact after

the end of the project and on how many target group members or other people.

25. Have you continued cooperation with your partners? yes no don’t know

26. How?

27. Why not?

28. Has your project led to new projects?

29. What kind of projects?

Please let us know the funding source of the project/s if applicable.

0

30. Rate the long-term impact/significance of your project at a general level.

very significant significant quite significant somewhat significant not at all significant don’t know

31. Other comments?

32. Would you be interested in participating in a short further interview relating

to this survey later?

The interviews will be carried out during October and November 2012 at a time

agreed on in advance with the participants.

yes no

1

Annex 2.

Leonardo da Vinci partnership projects in Finland between 2008–2012

Project number

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00083 3

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00087 2

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00096 4

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00108 3

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00108 6

2008-1-DE2-LEO04-00110 3

2008-1-EE1-LEO04-00068 3

2008-1-ES1-LEO04-00122 2

2008-1-ES1-LEO04-00129 4

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00101 1

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00102 1

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00103 1

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00111 1

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00111 6

2008-1-FI1-LEO04-00112 1

2008-1-FR1-LEO04-00294 5

2008-1-GB2-LEO04-00109 5

2008-1-IT1-LEO04-00022 2

2008-1-LT1-LEO04-00054 7

2008-1-LT1-LEO04-00077 4

2008-1-LT1-LEO04-00082 4

Name of the project Organisation

Intercultural Competence for employees in the social field (InCoso)

Healthy Trends in Kitchen - organic and sustainable aspects in food (Healhy Trends)

Partners Obinelli International (POInt)

Improvement of Traineeships in an International Context (ITIC)

Improvement of Traineeships in an International Context (ITIC)

Personalentwicklung für ältere Arbeitnehmer

SAMPO Estonian, Finnish and Icelandic Partnership project on National Epics in Arts and Culture