The Changing Situation of Electrical Apprentices Submission

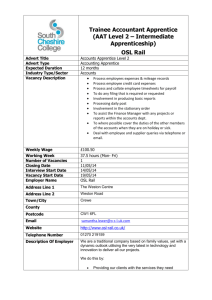

advertisement