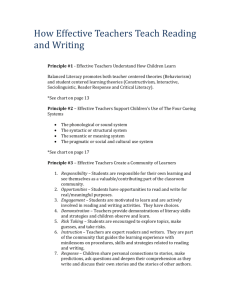

Balanced Literacy Curriculum Guide

advertisement