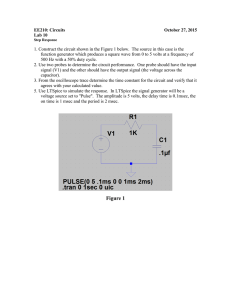

Lab 06: Time—Dependent Voltages

advertisement

PHYS 1420: College Physics II Fall 2009 Lab 06: Time—Dependent Voltages Introduction We have examined simple circuits using direct current, but no doubt you are aware that not all circuits operate under conditions of constant voltage. It is possible to construct a circuit in which the current must flow in a single direction (dc), but which has a voltage that varies with time. It is also possible to construct circuits in which the current flow (and hence the voltage) changes (direction and magnitude) with time. An oscilloscope permits us to observe an input voltage as a function of time, displaying the result as a two-dimensional graph. This visual representation is enormously handy for a conceptual understanding, but the display is also calibrated to permit accurate quantitative measurement of observed voltages. Objectives ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ Learn to operate the function generator and the oscilloscope Observe different forms of time-dependent voltages Construct basic RC circuits using multiple combinations of resistors and capacitors Measure the time constant τ of the circuit, and compare it to the predicted value Determine the accuracy of measurements made with the oscilloscope Equipment ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ Oscilloscope Electronic function generator O-scope probe and coaxial cables Assorted resistors Assorted capacitors Assorted wires Using the Function Generator and Oscilloscope The first step is simple: connect the function generator output directly to the oscilloscope input. All we want to accomplish here (without worrying about exactly how the function generator does what it does) is to view the generator signal on the o-scope screen (without worrying about exactly how the o-scope does what it does). ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ On the function generator, select the sine wave form. Set the frequency of the variation to about 200Hz. You should see the sine wave on the o-scope screen. If necessary, adjust the oscilloscope controls until you have a stable waveform displayed. Pay careful attention to exactly what happens whenever you twist a dial and change a scale. Amplitude: The amplitude of the sine wave (y-axis) represents voltage. Notice that by changing the volts/div scale on the o-scope, you can make the wave appear taller or shorter. This does not change the absolute amplitude of the wave, just its appearance. To control the absolute amplitude (actually, the maximum voltage), you can adjust the Output Level knob on the function generator. Period: The period of the wave is displayed in seconds (x-axis). If you change the time/div scale on the o-scope, the wave will appear stretched or compressed (notice that the amplitude of the wave remains unchanged). Pay careful attention to the units, making sure to note if they are ms (millisec=10–3s) or µs (microsec=10–6s). As before, changing the scale does not change the absolute value of the period. To change the actual period of the wave, you must adjust the function generator. Frequency: The frequency dial on the function generator can be used to vary the frequency within the limit set by the range button. This dial can be tricky to interpret properly, however. The minimum is labeled 0.2, and the maximum is labeled 2.0. This divides the selected range. For example, when the range button 200Hz is pressed, the frequency dial at its minimum(0.2), the wave frequency is 20Hz. When the dial is upped to 1.0, the new frequency is 100Hz. Only when the dial is set at 2.0 is the frequency 200Hz. Not particularly difficult, but easy to make a mistake if you aren’t paying attention. Remember that frequency is simply the inverse of period: f = 1 T This relationship can be verified quantitatively by noting the frequency on the generator, and the corresponding period on the o-scope. Adjust the frequency of your sine wave, then read the corresponding period from the oscilloscope. Verify that the values are inverse. Do this a few times, try out a few other frequency ranges (note how you have to adjust the time/div scale to keep a stable image on the screen), establish that the o-scope readings € are accurate compared to the frequency. Page 1 PHYS 1420: College Physics II ‣ Fall 2009 Now, just for fun, go ahead and observe what happens when you select another wave form. Again, pay attention to the adjustments you make, and notice what effect you are having. When you are proficient at reading and adjusting both the function generator and o-scope, you are ready to start using these tools to observe some properties of RC circuits. Function Generator O-scope RC Circuits We already know that when a single resistor is connected to a voltage source, that as long as the source voltage remains constant, so will the voltage across the resistor. What happens when we throw in a capacitor? Remember that the whole point of the capacitor is charge storage. As the capacitor charges, the voltage across it increases (Q = CV, so the charge is proportional to the voltage). As a function of time, however, the charge does not build up linearly. The capacitor fills faster when it is empty, and the fuller it gets, the more slowly additional charges accumulate. The RC circuits you will build are not very different from the simple DC circuits you examined last week. ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ ‣ Wire a resistor and a capacitor in a series circuit with a voltage source. In this case, your voltage source will be the function generator. The function generator should be in the square wave mode, which will provide a constant voltage (+) followed by the same constant voltage (—). The oscilloscope is, for all practical purposes, a voltmeter, and should be wired in parallel across the resistor. You may need to adjust both the oscilloscope and function generator, but you should see the charge and discharge cycle of the capacitor displayed on the o-scope screen, and it should look very much like the figure on the right. Notice how adjusting the frequency of the function generator affects the shape of the curve. You should use a frequency that allows the capacitor to completely charge and discharge over one cycle. The RC combinations provided will require low frequencies, so you should use the 200Hz range on the generator. ✦ Use the output level control on the function generator to vary the amplitude of your signal. For convenience, you should adjust the amplitude to match the scale on the left side of the o-scope display (0 to 100%). Optimally, you want a signal that has a min at 0 and a max at 100% of the scale (see the figure left). Note that you can also use the volts/div scale on the o-scope to adjust the appearance of your signal. ✦ Once you have a satisfactory signal displayed on the o-scope, use it to directly measure the time constant (τ) of the RC combination. The graph on the left illustrates this idea: one time constant (τ) is how long it takes for the capacitor to accumulate 63% of a full charge (why 63%? See Analysis below). It may be necessary to adjust the time/div scale on the o-scope to a setting that is easy to read. Make this measurement carefully, noting all the settings (in case you have to do-over). ✦ There are three RC combinations for you to observe and measure. Replace the initial RC pair with a different pair. Make the necessary adjustments and again measure the time constant. Repeat for the third RC pair. Do not forget to record the resistance and capacitance for each pair (printed on the component, along with tolerance) as well as the settings you have used and the time constant. Make the following qualitative observation for one RC pair. Adjust the frequency of the input signal (do not adjust the amplitude). What happens when the input frequency decreases? Sketch the charge-discharge curve in your notebook. Adjust the frequency up, decreasing the period of the oscillation. Again observe and sketch what happens to the observed output signal. Note if there is an upper or lower limit to the frequency for which the curve can be distinguished. The circuit diagram above shows that you have been observing the voltage across the resistor. For one RC pair, swap the positions of the resistor and capacitor. This will instead display the voltage across the capacitor as it charges and discharges. Note qualitatively the difference in what you see (and what you think it means). You may want to record a sketch in your notebook. Page 2 PHYS 1420: College Physics II Fall 2009 Data If you have not already, organize your data into a table that includes the resistance and capacitance of each pair (along with the uncertainty, or tolerance, of each), and the time constant you measured. This is a good time to double–check and verify the settings that you used and the accuracy with which you read the oscilloscope. Reduction and Analysis As you have demonstrated, the voltage across either the resistor or the capacitor varies with time, but not linearly. The shape of the curve that you have observed is exponential: t − Vc = Vo 1− e RC , where Vc is the voltage across the capacitor (shown on the o-scope), and Vo is the source voltage (function generator). Refer to section 18.3 of the text for a discussion of RC circuits (and to Appendix I(E) for a brief review of the exponential function). We can demonstrate easily the idea of the € time constant. Define the time constant τ: τ = RC where R and C are the resistance and capacitance of the components in the circuit. Watch what happens: t = RC= τ t = 2RC= 2τ t = 3RC = 3τ t = 4RC = 3τ t = 5RC = 3τ Vc = Vo[1 — e–1] Vc = Vo[1 — 0.368] Vc = 0.632Vo Vc = Vo[1 — e–2] € Vc = Vo[1 — 0.135] Vc = 0.865Vo Vc = Vo[1 — e–3] Vc = Vo[1 — 0.0498] Vc = 0.950Vo Vc = Vo[1 — e–4] Vc = Vo[1 — 0.0183] Vc = 0.982Vo Vc = Vo[1 — e–5] Vc = Vo[1 — 0.00674] Vc = 0.993Vo After five time constants have elapsed, the capacitor is effectively full. Notice that, because of the exponential, Vc approaches Vo asymptotically—it never actually gets there. So, to complete the circle: the time constant is defined explicitly because of the exponential function. There’s no physical reason why 63% of a full charge is significant (or particularly useful), but there is mathematical significance. 1. 2. 3. For each of the RC pairs you tested, calculate the expected time constant (τ = RC). Using the uncertainties stamped on the components, find the uncertainty in this predicted value. Determine the uncertainty in your experimentally observed time constants. The uncertainty associated with the time will be ½ the smallest division on the scale. For example, if the o-scope was set to the 1ms/div scale, the smallest division would be 0.2ms. The associated uncertainty would then be ±½(0.2ms) = ±0.1ms. The figure on the right shows the configurations for ”high pass” and “low pass” filters. A pass filter does exactly what it says: only allows specific frequencies to pass. A high-pass filter transmits high frequencies while blocking low. A low-pass filter does just the opposite, passing low frequencies and blocking high. The classic example of how these are useful? Your stereo speakers. The woofer needs a low-pass to prevent high-frequency hissing, while the tweeter needs a high-pass to allow only those higher frequency, higher pitched signals. Examine the observations you made above while adjusting signal frequency. Did you make a low-pass or high-pass filter? What was the approximate range of allowed frequencies? Page 3