Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research Potsdam

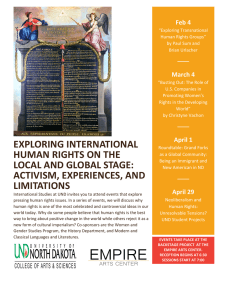

advertisement