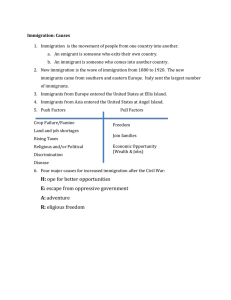

Immigration and the labour market

advertisement