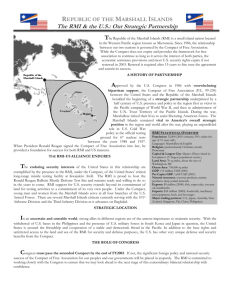

An Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change

advertisement