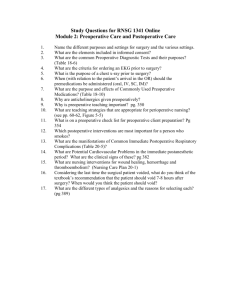

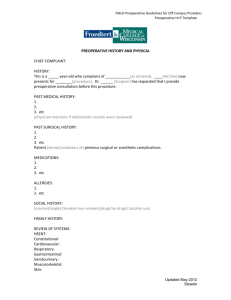

Practice Advisory for PreAnesthesia Evaluation

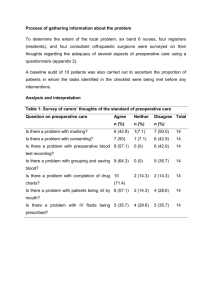

advertisement