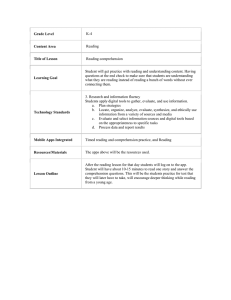

Knowledge for teaching reading comprehension

advertisement