Clarifying Gold-Plating

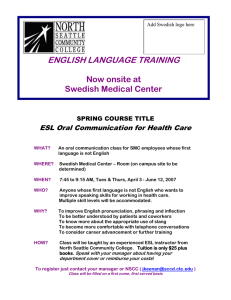

advertisement