Alternative Approval Process: A Guide for Local Governments in B.C.

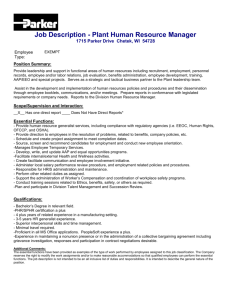

advertisement