Entscheidungsorientierte Ermittlung der

advertisement

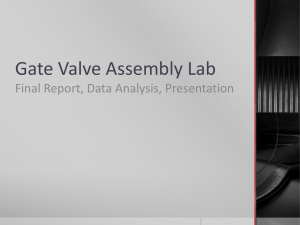

econstor www.econstor.eu Der Open-Access-Publikationsserver der ZBW – Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft The Open Access Publication Server of the ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics Blankart, Charles B.; Knieps, Günter; Zenhäusern, Patrick Working Paper Regulation of new markets in telecommunications? Market dynamics and shrinking monopolistic bottlenecks Diskussionsbeiträge // Institut für Verkehrswissenschaft und Regionalpolitik, No. 112 [rev.] Provided in cooperation with: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau Suggested citation: Blankart, Charles B.; Knieps, Günter; Zenhäusern, Patrick (2007) : Regulation of new markets in telecommunications? Market dynamics and shrinking monopolistic bottlenecks, Diskussionsbeiträge // Institut für Verkehrswissenschaft und Regionalpolitik, No. 112 [rev.], http://hdl.handle.net/10419/32309 Nutzungsbedingungen: Die ZBW räumt Ihnen als Nutzerin/Nutzer das unentgeltliche, räumlich unbeschränkte und zeitlich auf die Dauer des Schutzrechts beschränkte einfache Recht ein, das ausgewählte Werk im Rahmen der unter → http://www.econstor.eu/dspace/Nutzungsbedingungen nachzulesenden vollständigen Nutzungsbedingungen zu vervielfältigen, mit denen die Nutzerin/der Nutzer sich durch die erste Nutzung einverstanden erklärt. zbw Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre for Economics Terms of use: The ZBW grants you, the user, the non-exclusive right to use the selected work free of charge, territorially unrestricted and within the time limit of the term of the property rights according to the terms specified at → http://www.econstor.eu/dspace/Nutzungsbedingungen By the first use of the selected work the user agrees and declares to comply with these terms of use. Regulation of New Markets in Telecommunications? Market dynamics and shrinking monopolistic bottlenecks by C.B. Blankart*, G. Knieps**, P. Zenhäusern*** Discussion Paper Institut für Verkehrswissenschaft und Regionalpolitik No. 112 – August 2006 – Revised Version: January 2007 Abstract: This paper aims at localizing network-specific market power in new markets. Three kinds of transmission qualities on service markets can be differentiated according to the products provided: narrowband services like PSTN/ISDN or GSM, semi high-speed broadband services like broadband internet access up to 6 Mbps download and VDSL services up to 50 Mbps. As long as, due to the absence of alternative network infrastructures, a monopolistic bottleneck in local infrastructure networks exists the question arises what the remaining bottleneck components are for these different markets. In this paper the shrinkingbottleneck hypothesis will be demonstrated. * Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Faculty of Economics, Spandauer Straße 1, 10178 Berlin, Germany, e-mail: blankart@wiwi.hu-berlin.de ** Albert-Ludwigs-University, Institute for Transport Economics and Regional Policy, Platz der Alten Synagoge, 79085 Freiburg, Germany, e-mail: guenter.knieps@vwl.uni-freiburg.de *** Plaut Economics, Baslerstr. 37, 4600 Olten, Switzerland, e-mail: patrick.zenhaeusern@plaut.ch 1 1. Introduction From the very beginning of the EU liberalization of the telecommunications sector the focus was on the involvement of new and innovative telecommunications markets. In the meantime, an intention to avoid overregulation with respect to new markets can be observed in the EU telecommunications regulatory framework. A clear-cut economically based analysis of the remaining need for sectorspecific regulation is still missing. Such an approach should focus on a firm’s network-specific market power. A necessary requirement for future regulatory reform is the application of a so-called symmetrical regulatory approach. This means that regulation should focus on network-specific market power based on monopolistic bottlenecks with no intrinsic bias towards any firm or technology. The question is whether monopolistic bottlenecks will become more or less severe with the emergence of new markets. For that, we shall analyse three different markets for network services: narrowband services like PSTN/ISDN or GSM, semi high-speed broadband services like broadband internet access up to 6 Mbps download and VDSL services up to 50 Mbps. As long as, due to the absence of alternative network infrastructures, a monopolistic bottleneck in local infrastructure networks exists, the question arises what the remaining bottleneck components are that constitute necessary input for these different markets. In this paper the hypothesis of a shrinking bottleneck will be demonstrated. The paper starts with a description of the EU telecommunications policy regarding new markets since the abolishment of legal entry barriers (see section 2). From there it proceeds to explain the reference point, i.e. how the regulatory subject is to be defined based on network economics (see section 3). This part of the paper is followed by the implications for telecommunications regulation (see section 4). Conclusions are presented in section 5. 2 2. New markets and EU telecommunications policy EU telecommunications policy has played a key role in the process towards entry deregulation. The Commission of the European Communities has initiated a wide-ranging debate on the possibilities of completing the common internal market for telecommunications in the European Community. Obviously, this effort was strongly related to the Commission’s endeavour to complete the common market by 1992. The first step was towards open network provision (ONP) which was introduced to stimulate entry to the new markets for value added network services in 1990. Its aim was partial entry deregulation in order to establish non-discriminatory access to monopolistic network infrastructures (e.g. Knieps, 2001, p. 645).1 The Commission again strongly influenced the process of full liberalization of European telecommunications. The “Full Competition Directive”2 of 13 March 1996 obligated the member countries to allow free entry into all parts of telecommunications. The new telecommunications laws allowing overall market entry were enacted by the national parliaments during 1996, coming fully into effect on 1 January 1998. 2.1. EU regulatory framework 1998 As a consequence of global entry deregulation the question became relevant how the division of labor between sector-specific market power deregulation and general competition law ought to be realized. In the following we point out that EU telecommunications policy has so far been rather contradictory and inconsistent and therefore has not been successful in implementing an economically based concept for preventing the abuse of sector-specific market power. 1 2 Council Directive 90/387/EEC of 28 June 1990 on the establishment of the internal market for telecommunications services through the implementation of open network provision, OJ L 192, 24. 7. 1990, p.1. Commission Directive 96/19/EC of 13 March 1996 amending Directive 90/388/EEC with regard to the implementation of full competition in the telecommunications markets, OJ L 74, 22. 3. 1996, p. 13. 3 A first important corner stone within the EU-ONP-regulation followed with the European Commission’s “Access Notice”.3 This document pointed out the importance of the concept of the “essential facilities” indispensable for reaching customers (section 68) within the context of EU competition law, in particular Article 82 (e.g. Ungerer, 2000, p. 217). The expression “essential facilities” is used to describe a facility or an infrastructure which is essential for reaching customers and/or enabling competitors to carry on their business, and which cannot be replicated by reasonable means. With the supply of access to the facility to one or more competitors the abuse of a dominant position and the possibility of thus preventing the emergence of a new product or service should be avoided (see Ungerer, 2000, p. 229). 2.2. EU Review 1999 and EU regulatory framework 2003 In 1999 a EU Review started with the aim of maximizing the application of the general European competition law, the minimization of sector-specific regulation, a rigorous phasing out of unnecessary regulation, and the introduction of “sunset” clauses. Nevertheless, the unspecific regulatory obligations based on the EU Directives of the 1999 Review package, in particular the Framework Directive4, and the Access Directive5 resulted in a tangle of contradictory decisions and statements (see Knieps, 2005, p. 78). The Commission’s Guidelines (see European Commission, 2002) do not present a clear and economically wellfounded concept for localising network-specific market power. Markets are defined and market power assessed using the same methodologies as under competition law (see European Commission, 2002, recital 24). In particular, in order to identify significant market power (SMP), the Commission’s Guidelines formu3 4 5 Notice on the application of the competition rules to access agreements in the telecommunications sector.- Framework, Relevant Markets and Principles (98/C265/02), Official Journal of the European Communities, 22. 8. 98, pp. 2-28. Directive 2002/21/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 March 2002 on a common regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services (Framework Directive), OJ L108/33, 24. 4. 2002. Directive 2002/19/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on access to, and interconnection of, electronic communications networks and associated facilities (Access Directive), OJ L108/7, 24. 4. 2002. 4 late a long list of criteria indicating the existence of a dominant position. These criteria include: overall size of the undertaking, control of infrastructure not easily duplicated, technological advantages or superiority, absence of or low countervailing buying power, easy or privileged access to capital markets/financial resources, product/services diversifications, economies of scale, economies of scope, vertical integration, a highly developed distribution and sales network, absence of potential competition, barriers to expansion (see European Commission, 2002, recital 78). Even the criteria of general competition law are not considered consistently. It is stressed, however, that the existence of a dominant position cannot be established on the sole basis of large market shares and would require a thorough and overall analysis of the economic characteristics of the relevant market (European Commission, 2002, recital 78). In contrast to the Access Notice, it is argued that the doctrine of the ‘essential facilities’ would be less relevant for the purposes of ex ante applying Article 14 of the Framework Directive than ex post applying Article 82 of the EC Treaty (see European Commission, 2002, recital 82).6 At the same time, special rules were developed focusing on the emergence of new markets or new products. The application of the essential facilities doctrine in the context of article 82 EC Treaty has been considered as relevant where the refusal to supply or to grant access to third parties would limit or prevent the emergence of new markets or new products (see European Commission, 2002, recital 81). Moreover, recital 9 of the Commission’s Guidelines of 2002 states: “however, given the dynamic character and functioning of electronic communications markets, possibilities to overcome barriers within the relevant time horizon have also to be taken into consideration when carrying out a prospective analysis to identify the relevant markets for possible ex ante regulation.” Recital 15 states: “Furthermore, new and emerging markets in which market power may be found to exist because of ‘first-mover’ advantages should not in principle be subject to ex-ante regulation”. Nevertheless, within the Annex of the same Recommendations the markets considered for possible regulation may also include new markets, such as interactive cable television (see market 12 wholesale 6 This is a definite step away from the Access Notice of August 1998, pointing out the importance of ensuring non-discriminatory access to essential facilities. 5 broadband access). The Commission stated: “When there is effective facilitiesbased competition, the new framework will require ex-ante regulatory obligations to be lifted. Investment in new and competing infrastructures will bring forward the day when such obligations can be relaxed (see European Commission, 2003b, p. 6). 2.3. Review 2006 of EU regulatory framework 2003 As a consequence, the future scope of sector-specific regulation regarding new markets remained undecided. In 2003, however, the European Commission recommended the so-called “three criteria test”. This test seems to substantiate the requirements for regulatory intervention. The Commission summarizes the three criteria as follows “The first criterion is the presence of high and non-transitory entry barriers whether of structural, legal or regulatory nature. … the second criterion admits only those markets, the structure of which does not tend towards effective competition within the relevant time horizon. …. The third criterion is that application of competition law alone would not adequately address the market failure(s) concerned” (see European Commission, 2003a, recital 9). Thus it can be concluded that within the EU telecommunications regulatory framework an intention to avoid overregulation with respect to new markets can be observed. However, an economic approach to the remaining need for sectorspecific regulation is still missing. For that, a two-stage procedure is necessary. First, the basis for intervention has to be localized. Then, for those markets, and only for those, where market power has been identified, appropriate measures should be designed and enforced. The criteria on which these measures are based are general in the sense that they apply to all network industries (see Knieps, 2006a, pp. 53-55). In the following it is shown, that the “three criteria test” can be applied in accordance with the theory of monopolistic bottlenecks. 6 3. New markets and network-specific market power regulation 3.1. Localization of monopolistic bottlenecks EU telecommunications policy has been strongly influenced by asymmetric market power regulation with an intrinsic bias against incumbent carriers. Excessive regulation due to an oversized regulatory basis has occurred (e.g. Knieps, 2005). The specification of the regulatory basis is not explicitly founded on the identification of network-specific market power, instead classification as a dominant firm as laid down in competition law is chosen as the central precondition to justify sector-specific regulation. For example, the provision of long-distance telecommunications infrastructure and voice telephony services by a carrier classified as dominant on those markets has been considered noncompetitive without considering whether active or potential competition might be sufficient to discipline market power. A necessary requirement for future regulatory reform is the application of a regulatory approach, focussing on network-specific market power based on monopolistic bottlenecks with no intrinsic bias towards any firm or technology (e.g. Knieps, 2006a, pp. 51-59). Criteria like relative market share, financial strength, access to input and service markets etc. can only serve as a starting point in order to evaluate the existence of market power; but the development of an ex ante regulatory criterion creates a need for a more clear-cut definition of market power. This is even more important, because “criteria for conjecturing a dominant position” on the basis of market shares can lead to wrong criteria for government intervention in network industries. It is important to identify the regulatory basis by means of Stigler’s concept of entry barriers, focussing on the long-run cost asymmetries between incumbent and potential entrants.7 The sector-specific characteristics of network structures (economies of bundling) are not a sufficient reason to conclude that market 7 “A barrier to entry may be defined as a cost of producing (at some or every rate of output) which must be borne by a firm which seeks to enter an industry but is not borne by firms already in the industry” (Stigler, 1968, p. 67). 7 power must exist.8 It is necessary to differentiate between those areas in which active and/or potential competition can work and other areas, so-called monopolistic bottleneck areas, where a natural monopoly situation (due to economies of bundling) in combination with sunk (irreversible) costs exists. Sunk costs are no longer decision-relevant for the incumbent monopoly, whereas the potential entrant is confronted with the decision whether or not to build network infrastructure and thus spend the irreversible costs. The incumbent firm therefore has lower decision-relevant costs than potential entrants. This creates scope for strategic behaviour on the part of the incumbent firm, so that monopoly profits (or inefficient production) will not necessarily result in market entry. Regulation of network-specific market power is only justified in monopolistic bottleneck areas. In all other cases, the existence of active and potential competition will lead to efficient market results. The theory of monopolistic bottlenecks has been developed to provide a consistent analytical basis to identify network-specific market power in all network industries, irrespective whether they are static or dynamic. As soon as from an ex ante perspective either the natural monopoly condition or the sunk costs or both become irrelevant, market power regulation becomes obsolete. Thus the necessity of regulation has to be investigated periodically. The development of alternative infrastructures should not be disturbed by regulatory interventions. Neither the subsidization of competing infrastructures nor access holidays to allow excessive profits for a certain period are justified because in both cases the competitive reference point of a market-based rate of return on invested capital is distorted. Due to the sequential nature of investment decisions (ex ante) and regulation of access tariffs (ex post) a regulation-induced hold-up problem 8 The pressure of potential competition can be sufficient to discipline the behaviour of the active supplier, even if he is the owner of a natural monopoly. Such networks are called “contestable” (Baumol, Panzar, Willig, 1982). It seems obvious that, as soon as competition works, the behaviour of markets for network services becomes more complex than is assumed in the “simple” model of the theory of contestable markets. Examples may be strategies of network differentiation, product differentiation, price differentiation, creation of goodwill etc. However, even strategic behaviour on competitive markets for network services should not lead to the opposite conclusion to re-regulate these markets. In contrast, the very point of the disaggregated approach is the development of the preconditions for competition on the markets for network services. 8 would arise. The truncation problem would result in rewarding only ex post successful projects, whereas the ex ante risks of project failure would not be compensated.9 In order to avoid ex post cheating by the regulator’s ignoring investors’ ex-ante risk, the solution cannot be to favour the application of a wrong regulatory instrument. Instead of “access holidays” a disaggregated regulatory contract on the statutory level (EU Directives and law of the member states) should be applied, which guarantees that the regulation is limited to the monopolistic bottlenecks and that the applied regulation does not deter the recovering of the ex ante opportunity cost of capital (see Knieps, 2005, pp. 88-91). The network economic concept of monopolistic bottlenecks suggests a connection with the essential facilities doctrine resulting from US antitrust law, which is now also being used increasingly in European competition law.10 In accordance with this doctrine, a facility can only be regarded as essential if the following two conditions are fulfilled: (1) market entry to the complementary market is not actually possible without access to this facility, and (2) providers on the complementary market cannot, using reasonable effort, duplicate the facility; substitutes do not exist either (e.g. Areeda, Hoverkamp, 1988).11 The application of the essential facilities doctrine means that a traditional instrument of competition law can be used as a regulatory instrument. A facility is regarded as essential when it fulfils the criteria for classification as a monopolistic bottleneck facility in the context of the disaggregated regulatory approach. The starting point for this approach is to differentiate between those network areas in which active and/or potential competition is possible, and those network areas in which stable network-specific market power can be localized. 9 Under certain conditions it can even be shown that regulated access prices equal to short run variable costs would result in a unique Nash equilibrium and the utility would not invest (Newbery, 2000, pp. 34-36). 10 This means that access to ports, airports or railway networks can neither be refused, nor granted under conditions that penalize competitors, without factual justification. 11 The fact that use of this facility is essential for competition on the complementary market is occasionally expressed as a third criterion, as it reduces prices or increases the volumes offered. This third criterion, however, only describes the effects of access. 9 The disaggregated regulatory approach involves applying the essential facilities doctrine not only on a case-by-case basis, but to a category of cases, namely to monopolistic bottleneck facilities. If the relevant market does not have the characteristics of a natural monopoly, the application of the essential facilities doctrine would not only be pointless, but detrimental (e.g. Lipsky, Sidak, 1999, p. 1220). The non-discriminatory conditions of access to the essential facilities must be set out in more detail as part of the disaggregated regulatory approach. In doing so, the application of the essential facilities doctrine must be seen in a dynamic context. The aim must therefore also be to design the conditions of access so as not to hinder infrastructure competition, but instead create an incentive for research and development, innovations and investments at the facility level. This is the only way to establish a balanced relationship between services and infrastructure competition. 3.2. Implications for new markets It is important to differentiate between network services and network infrastructure. Service markets should not be regulated, irrespective of whether they are old or new. Due to the absence of sunk costs no long run asymmetry between active providers and potential entrants exist, irrespective of whether firms possess high market shares or network externalities are relevant (see Knieps, 2006a, p. 52)12. The question whether regulation of new markets could be justified is pointless on new markets for network services, because they are competitive. As far as infrastructure is concerned, one has to distinguish between competitive infrastructures and monopolistic bottlenecks. Regulation is required only for the latter, as duplication is unreasonably expensive. The former, however, should not be regulated as barriers to entry are absent. Rather, competition should not be hampered in order to promote innovation and growth. It would be wrong in particular to regulate access to a level below market price on this part of the in12 Although network externalities do not create network-specific market power, its occurrence does not provide an argument in favour of price-structure regulation of monopolistic bottlenecks instead of incentive regulation (Knieps, 2006a, p. 66). 10 frastructure in order to provide cheap access to service providers. Such an endeavour would reduce incentives to invest in infrastructure, diminish competitive search and pre-empt technological development. It is also not justified to regard regulation holidays as a substitute for patent protection. Such a substitute is not required as every provider of a new service can apply for patent protection if she believes that her service or a component of it is an invention. Inventions have to be protected because access is too easy. For bottlenecks, in contrast, access is never too easy, but rather too restrictive. New services markets cannot be compared to a situation where certain actors should be protected like owners of patents. Patents have the function of fostering competition for the development of new knowledge in society and optimal patent law only guarantees a competitive rate of return for the industry, although the patent holder gains a monopoly rent for a certain period. In contrast, the owner of a monopolistic bottleneck is the only investor taking an ex ante risk. Therefore in an unregulated situation excessive monopoly rents occur. Thus, the analogy between network-specific market power of monopolistic bottlenecks and patent rents fails completely. If a communications company indeed obtains a patent for new equipment, which is used as input to provide a service or infrastructure innovation, the patent law is applicable anyway. In order to allow active and potential competition on service markets, in particular new service markets, non-discriminatory access to monopolistic bottlenecks is necessary. To the extent that a monopolistic bottleneck is observable, ex ante regulation should be in place; otherwise the evolution of new service markets will be hampered. Innovative ways of access to existing bottlenecks should be guaranteed in order to allow the evolvement of new service markets. The owner of the monopolistic bottleneck can neither be forced to extend its infrastructure nor to do disinvestments. The reference point for economically efficient investment signals is a market rate of return and not a monopolistic profit. Therefore, price cap regulation of a monopolistic bottleneck should not prevent the coverage of stand alone cost. If demand for access increases it is in the owner’s interest to expand the facility and vice versa if demand decreases. Thus 11 the overall responsibility for the facility can remain with the owner. Similarly, competitors are given correct signals to invest in alternative facilities. In particular, incremental investments, which are necessary to provide innovative network access, are to be covered by the demander of this innovative access. The overall responsibility for the network infrastructure remains with the network owner; otherwise regulation would foster network fragmentation. Incentive regulation in order to limit the level of access charges is necessary and should not be superseded by the argument of the importance of stimulating alternative infrastructure platforms. Unregulated monopolistic profits would result in investments into alternative access platforms and subsequent distortion between infrastructure and service competition. Convergence of the telecommunications and information technology sectors and resulting infrastructure competition should lead to a phasing out of bottleneck regulation rather than the extension of the regulatory basis. 4. Lessons for telecommunications regulation In this section the implications of the theory of monopolistic bottlenecks for new telecommunications markets are derived in detail. 4.1. Towards one consistent theory: The three criteria test reconsidered In recent years the focus of regulatory attention has increasingly shifted towards incentives for investment. In this context the implementation of so-called ‘access holidays’ has been proposed in order to protect investment incentives (e.g. Gans, King, 2003, p. 164; Baake et al., 2005). This means that it is guaranteed by the regulator that certain innovations, such as e.g. ‘Next Generation Networks’, are not regulated during a specific period of time. Thus, access holidays are a significant period during which an investor is free from access regulation. The idea is that such a holiday will increase investment incentives by allowing profits unhindered by regulatory intervention. 12 Dahlke and Neumann (2006) refer to the Framework Directive, where in recital 27 it is pointed out that the Commission should draw guidelines which “will also address the issue of newly emerging markets, where de facto the market leader is likely to have a substantial market share but should not be subjected to inappropriate obligations”. They note that this text passage could be interpreted as a leave of absence of sector-specific regulation and argue against this reading, however without showing why further regulation of telecommunications markets could be justified. It is a mere pleading to maintain the status quo of the current regulatory system, not an explanation of how sector-specific regulation may evolve based on sound economics. Because regulation from this point of view should be a well founded exemption in a free market economy, maintaining the status quo has to be justified as well. Access holidays with the goal of a delayed application of regulation can only be a relevant concept if regulatory problems of network-specific market power still exist. Market dynamics can indeed reduce regulatory requirements or make them completely superfluous. As long as network-specific market power does exist, it should be regulated, as soon as it has vanished, regulation should stop. In both cases “access holidays” are the wrong regulatory instrument, either resulting in over- or in underregulation. In any case, cementing the status quo would be inadequate as well (e.g. Knieps, 2005, pp. 88-91). In order to provide a consistent regulatory framework, the three criteria in the Commission Recommendation of February 2003 (see European Commission, 2003a, recital 9) have to be rewritten in economic terms. The presence of high and non-transitory entry barriers – criteria one – could be defined in economic terms as a natural monopoly in combination with sunk costs (monopolistic bottlenecks). Markets that do not tend towards effective competition within the relevant time horizon – criteria two – could be rewritten, stating that a monopoly in combination with sunk costs is stable over a foreseeable future without phasing-out potential. That the application of competition law alone would not adequately address the market failure(s) concerned – criteria three – requires the consideration whether ex ante or ex post intervention is more efficient. Indeed, the theory of monopolistic bottleneck requires ex ante regulation of network- 13 specific market power consisting of mandatory access, instead of negotiated third party access (Knieps, 2006b). Non-discriminatory access should not be implemented by ex post case law, but by ex ante regulation avoiding monopolistic access charges by incentive regulation. Only through a specific disaggregated access regulation can potentials of service and infrastructure competition be exhausted. There will be no technology policy induced bias of competition of innovation. Irrespective of market proportions, no network-specific market power exists on new service markets. It is possible, however, that new service markets create a necessity for a wider unbundling of the local loop. The development of the three criteria in the Commission Recommendation of February 2003 (see European Commission, 2003a, recital 9) can be seen as a refinement of the essential facilities doctrine. So on one hand there are wellfounded principles, which can be substantiated by the theory of monopolistic bottlenecks, on the other hand there is a practice that thwarts these principles. Two examples may illustrate this: (1) If the three criteria had been applied consistently, no end user market would have been recommended to be presumably in need of regulation (see Knieps, 2005). Also, input markets, such as interactive cable television, internet etc., would have been specified in more detail. There, e.g. on the basis of the Cable Review (see European Commission, 1998), conditions could have been developed that would have made regulation unnecessary. (2) In European Commission (2003a, recital 15), the notion of “new and emerging markets” in which market power may be found to exist because of “first-mover” advantages, is not economically adequate. It is not clear whether the term refers to new services, new infrastructures etc. And independently of this, a “first-mover” advantage is never a reason for sector-specific regulation, because it does not create a long-run cost asymmetry (see Stigler, 1968, pp. 67-70). 14 Therefore, it is important to emphasize that there is one consistent theory for localizing network-specific market power. Network economics does provide sound economic principles independent of the status of a market, e.g. whether it is an old or an emerging one. The following conclusions can be drawn: (1) If competing infrastructure platforms do exist, sector-specific market power regulation is no longer justifiable. This statement is in accordance with the first criterion postulated by the EU Commission and can be substantiated by the theory of monopolistic bottlenecks. (2) If a bottleneck is not stable for the decision-relevant time horizon, regulation of sector-specific market power should be phased out. This statement is in accordance with the second criterion of the Commission Recommendation, which states that only those markets should be subject to regulation, the structure of which does not tend towards effective competition within the relevant time horizon. (3) The essential facilities doctrine is to be applied independent of whether markets are old or new. Concerning this matter, the Access Notice should be kept in mind. Mandatory access instead of negotiated third party access should be implemented in order to guarantee non-discriminatory access to monopolistic bottlenecks. This requirement is in accordance with the third criterion of the Commission Recommendation. “Access holidays” are not a solution to regulatory problems. Seemingly, what qualifies as a monopolistic bottleneck is still as controversial today as it was some years ago, when the notion of the bottleneck was generally not limited to monopolistic bottlenecks. Ungerer (2000, p. 235) e.g. showed a table headed “Network Access requirements of Service Providers”, including technical functions of coordination (e.g. numbering schemes which belong in the field of technical regulation). 15 The question arises whether new markets create new bottlenecks or extend the borderlines of existing bottlenecks. Since there are competing long-distance networks, the focus is on network access. In the current debate, the relevancy of one superior fiber-to-the-home network is excluded. Instead, a multiplicity of alternative upgrading strategies seems possible, together with competing infrastructure platforms. The fiber to the curb upgrading strategy of Deutsche Telekom is only one example (c.f. Büllingen, Stamm, 2001, 61f.). Competing infrastructure platforms result in monopolistic infrastructure competition. The natural monopoly paradigm disappears and subsequently the need for bottleneck regulation disappears also. As long as competing network infrastructure does not exist, remaining bottleneck regulation is relevant. However, the borderline of the bottleneck does not expand. There is a multiplicity of upgrading strategies based on copper-wired loops as well as based on ductwork etc. Fibre cables similar to DSLAM are part of upgrading infrastructure and do not belong to the remaining bottleneck. 4.2. Platform competition vs. access regulation to ducts: A practical application Sector-specific regulation of services lacks any economic basis. Neither old nor new services are a case for sector-specific market power regulation; the question is always whether upstream markets create monopolistic bottlenecks for competitors. Three kinds of transmission qualities on service markets can be differentiated according to the products provided: − Narrowband services like PSTN/ISDN, GSM − Semi high-speed broadband services like broadband internet access up to 6 Mbps download and − VDSL services up to 50 Mbps 16 Bottleneck components to local access As long as, due to the absence of alternative network infrastructures, a monopolistic bottleneck in the local infrastructure network exists, the question arises what the remaining bottleneck components are for these different markets. In the following we will demonstrate the shrinking-bottleneck hypothesis (see following chart). Local switch Copper wire loop Copper wire loop Ducts & ductworks Ducts & ductworks Ducts & ductworks PSTN/ISDN DSL VDSL Market dynamics for end consumer services For narrowband services like PSTN/ISDN the components belonging to the monopolistic bottleneck are local switch facilities, copper loops, ductworks and ducts. In order to provide DSL services, local switch facilities are no longer necessary. Access to copper cable is necessary. Competing providers can implement alternative network upgrading strategies, e.g. upgraded copper cable by DSLAMs. Modems etc. are definitely not assets that can be characterized as sunk costs. A parallel investment into modems cannot be considered as socially inefficient cost duplication, because this is the only way to achieve the potentials for a large scope of innovative network services. The provision of VDSL services is not possible without investing into fibre to the curb or fibre to the home. In order to be able to apply upgrading strategies by 17 means of fibre cable, access to ductworks and ducts is necessary. A roll out of fibre optic networks does not require a duplication of ductworks. Rather, fibre cables can be laid between relevant points in existing ductworks. Fibre cables, cabinets and optical modems are components of upgrading infrastructure in order to provide VDSL-services. Similar to the situation of competing upgrading strategies by DSLAM on the basis of copper, competing upgrading strategies by means of fibre cables and other upgrading components are possible on the basis of ducts and ductworks. As an alternative to local telecommunications network infrastructures, ducts and ductworks from electricity or water companies may be available as well. Thus, ex ante regulation of access to ducts and ductworks is required, if the following two conditions are fulfilled: (1) Alternative infrastructures for end customers (e.g. interactive broadband cable) are not in place; (2) Alternative duct networks, which can be upgraded for VDSL-purposes at reasonable cost, are not available. A differentiated unbundling and concomitant incentive regulation is then required, consisting of an accounting separation regime (e.g. European Commission, 2005) in combination with price cap regulation. Only then, alternative carriers are able to be become active in upgrading investments (e.g. fibre, modems) in order to provide VDSL-services. This case is interesting from the point of view of the situation in Switzerland. Almost all Swiss households have a choice between more than one network internet access provider. Access regulation to ducts and ductworks therefore was only implemented based on the revised telecommunications law13 to ensure that access to these facilities is guaranteed in cases where competing infrastructures are not yet in place. 13 Fernmeldegesetz (FMG), revision of the Swiss Telecommunications Act of March 24, 2006, Art. 11 (1. f.) (http://www.admin.ch/ch/d/ff/2006/3565.pdf). 18 The crucial question is whether there are input markets that an operator needs to have access to in order to deliver services to (end) customers and which are characterized as monopolistic bottlenecks. In a world where several IP-based high-speed platforms are competing, no market power regulation at all will be necessary. Products like IPTV, IP-Telephony, very high-speed internet access etc. are delivered over several different platforms. In this case, if some competitors, due to their path dependency, continue to use an older technology, e.g. PSTN/ISDN, none of these high-tech platform providers should be forced to support this older technology, only to afford their rivals customer access. The entrepreneurial decision to stop offering services based on outdated technologies that some competitors still depend upon should not be impeded by regulators. It is important to see that the competence for network design should always remain with the network operator. On the basis of the essential facilities doctrine, regulators cannot force a network operator either to build a new network, or to upgrade an established one, or to rebuild a network (e.g. to abrogate switches or copper loops). This shows that the theory of monopolistic bottlenecks is capable of meeting concerns regarding the dynamic development of telecommunications, although the criteria for localizing network-specific market power possess similar validity for other (stationary) network sectors. Criteria for defining where network-specific market power still remains do not depend on the emergence of new markets. Nevertheless, ultimately the market dynamics of service markets will inevitably lead to a shrinking of the monopolistic bottleneck within the local loop. 5. Conclusions Our main results can be summarized in five points: (1) There are intentions within the EU to reduce the extent of regulation, in particular regarding new telecommunications services. The EU Commission’s endeavour is, however, not specifically network oriented. 19 (2) Therefore the Commission ends up with a regulation that is too broad and not targeted toward monopolistic bottlenecks which represent the main problem of competition in telecommunications. (3) Alternatively, we propose an economic approach to regulation for the field of telecommunications. We focus on network-specific market power as the relevant long term entry barrier preventing competition. In the course of dynamic network and service competition, network-specific market power is likely to shrink. (4) In order to provide a consistent regulatory framework the three criteria test has to be reformulated. Former high and non-transitory entry barriers (criteria one) now become natural monopoly barriers in combination with sunk costs. Lack of a tendency towards effective competition within the relevant time horizon (criteria two) should be rewritten stating that a natural monopoly in combination with sunk costs is stable over a foreseeable future. The application of competition law alone would not adequately address the market failure(s) concerned (criteria three). Instead, ex ante regulation of network-specific market power, consisting of non-discriminatory mandatory access and incentive regulation of access charges, is required. (5) Practical evidence supports the hypothesis of a shrinking monopolistic bottleneck. The example of Switzerland moreover shows that alternative broad band network carriers are feasible in one market and that regulated access to duct networks can open access to network suppliers in those areas where alternative broad band infrastructure is not yet available. 20 References Areeda, P. & Hoverkamp, H. (1988). An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application, Antitrust Law, 1988/Supp. Baake, P., Kamecke, U. & Wey, C. (2005). A Regulatory Framework for New and Emerging Markets, Communications and Strategies, 60 (4th Quarter), 123-136. Baumol, W.J., Panzar, J.C. & Willig, R.D. (1982). Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure, San Diego. Bülligen, F. & Stamm, P. (2001). Entwicklungstrends im Telekommunikationssektor bis 2010, Studie im Auftrag des Wirtschaftsministeriums für Wirtschaft und Technologie, Bad Honnef. Dahlke, P. & Neumann A. (2006). Innovationen und Investitionen durch Regulierun, Telekommunikationsrecht, CR 6, 377-383. European Commission (1998). Commission communication concerning the review under competition rules of the joint provision of telecommunications and cable TV capacity over telecommunication networks, OJ C71, 7.3. 1998 European Commission (2002). Guidelines on market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the Community regulatory framework for electronic communications network and services, Official Journal of the European Communities, C 165/6-31, 11.7.2002. European Commission (2003a). Recommendation of 11 February 2003 on relevant product and service markets within the electronic communications sector susceptible to ex ante regulation in accordance with Directive 2002/21/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on a common regulatory framework for electronic communication networks and services (2003/311/EC), Official Journal of the European Union, 8.5.2003, L 114/4549. European Commission (2003b). Electronic Communications: the Road to the Knowledge Economy, Brussels, 11.2.2003, COM(2003) 65 final. European Commission (2005). Commission Recommendation of 19 September 2005 on accounting separation and cost accounting systems under the regulatory framework for electronic communications (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/698/EC), Official Journal of the European Union, 11.10.2005, L 266/64. 21 Gans, J. & King, S. (2003). Access Holidays for Network Infrastructure Investment, Agenda 10 (2), 163-178. Knieps, G. (2001). Regulatory Reform of European Telecommunications: Past Experience and Forward-Looking Perspectives, European Business Organization Law Review, 2, 641-655. Knieps, G. (2005). Telecommunications markets in the stranglehold of EU regulation: On the need for a disaggregated regulatory contract, Journal of Network Industries, 6, 75-93. Knieps, G. (2006a). Sector-specific market power regulation versus general competition law: Criteria for judging competitive versus regulated markets, in: Sioshansi, F.P., Pfaffenberger, W. (eds.), Electricity Market Reform: An International Perspective, Elsevier, Amsterdam et al., 49-74. Knieps, G. (2006b). The different role of mandatory access in German regulation of railroad and telecommunications, Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 2, 149-158. Lipsky, A.B. & Sidak, J.G. (1999). Essential Facilities, Standford Law Review 51, 1187-1249. Newbery, D.M. (2000), Privatization, Restructuring, and Regulation of Network Utilities, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London Stigler, G.J. (1968). Barriers to Entry, Economies of Scale, and Firm Size, in: G.J. Stigler, The Organization of Industry, Irwin, Homewood, Ill., 67-70. Ungerer, H. (2000), The Case of Telecommunications in the EU, in: C.-D. Ehlermann, L. Gosling (Eds.), European Competition Law Annual 1998: Regulating Communications Markets, Hart Publishing, Oxford and Portland, Oregon, 211-236. 22 Als Diskussionsbeiträge des Instituts für Verkehrswissenschaft und Regionalpolitik Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. sind zuletzt erschienen: 88. G. Knieps: Does the system of letter conveyance constitute a bottleneck resource? erscheint in: Proceedings of the 7th Königswinter Seminar „Contestability and Barriers to Entry in Postal Markets“, November 17-19, 2002 89. G. Knieps: Preisregulierung auf liberalisierten Telekommunikationsmärkten, erschienen in: Telekommunikations- & Medienrecht, TKMR-Tagungsband, 2003, S. 32-37 90. H.-J. Weiß: Die Doppelrolle der Kommunen im ÖPNV, erschienen in: Internationales Verkehrswesen, Jg. 55 (2003), Nr. 7+8 (Juli/Aug.), S. 338-342 91. G. Knieps: Mehr Markt beim Zugang zu den Start- und Landerechten auf europäischen Flughäfen, erschienen in: Orientierungen zur Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftspolitik 96, Juni 2003, S. 43-46 92. G. Knieps: Versteigerungen und Ausschreibungen in Netzsektoren: Ein disaggregierter Ansatz, erschienen in: Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Verkehrswissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft: Versteigerungen und Ausschreibungen in Verkehrs- und Versorgungsnetzen: Praxiserfahrungen und Zukunftsperspektiven, Reihe B, B 272, 2004, S.11-28 93. G. Knieps: Der Wettbewerb und seine Grenzen: Netzgebundene Leistungen aus ökonomischer Sicht, erschienen in: Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband (Hrsg.), Verbraucherschutz in netzgebundenen Märkten – wieviel Staat braucht der Markt?, Dokumentation der Tagung vom 18. November 2003, Berlin, 2004, S. 11-26 94. G. Knieps: Entgeltregulierung aus der Perspektive des disaggregierten Regulierungsansatzes, erschienen in: Netzwirtschaften&Recht (N&R), 1.Jg., Nr.1, 2004, S. 7-12 95. G. Knieps: Neuere Entwicklungen in der Verkehrsökonomie: Der disaggregierte Ansatz, erschienen in: Nordrhein-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Hrsg.), Symposium „Transportsysteme und Verkehrspolitik“, Vorträge 17, Schöningh-Verlag, Paderborn, 2004, S. 13-25 96. G. Knieps: Telekommunikationsmärkte zwischen Regulierung und Wettbewerb, erschienen in: Nutzinger, H.G. (Hrsg.), Regulierung, Wettbewerb und Marktwirtschaft, Festschrift für Carl Christian von Weizsäcker, Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, S. 203-220 97. G. Knieps: Wettbewerb auf den europäischen Transportmärkten: Das Problem der Netzzugänge, erschienen in: Fritsch, M. (Hrsg.), Marktdynamik und Innovation – Gedächtnisschrift für Hans-Jürgen Ewers, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 2004, S. 221-236 98. G. Knieps: Verkehrsinfrastruktur, erschienen in: Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung (Hrsg.), Handwörterbuch der Raumordnung, Hannover 2005, S. 12131219 99. G. Knieps: Limits to the (De-)Regulation of Transport Services, erschienen als: “Delimiting Regulatory Needs” in: OECD/EMCT Round Table 129, Transport Services: The Limits of (De)regulation, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2006, S.7-31 23 100. G. Knieps: Privatisation of Network Industries in Germany: A Disaggregated Approach, erschienen in: Köthenbürger, M., Sinn, H.-W., Whalley, J. (eds.), Privatization Experiences in the European Union, MIT Press, Cambridge (MA), London, 2006, S. 199-224 101. G. Knieps: Competition in the post-trade markets: A network economic analysis of the securities business, erschienen in: Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, Vol. 6, No.1, 2006, S. 45-60 102. G. Knieps: Information and communication technologies in Germany: Is there a remaining role for sector specific regulations?, erscheint in: Moerke, A., Storz, C. (Hrsg.), Institutions and Learning in New Industries, RoutledgeCurzon, 2006 103. G. Knieps: Von der Theorie angreifbarer Märkte zur Theorie monopolistischer Bottlenecks, November 2004, revidierte Fassung: Juni 2005 104. G. Knieps: The Different Role of Mandatory Access in German Regulation of Railroads and Telecommunications, erschienen in: Journal of Competition Law and Economics, Vol. 2/1, 2006, S. 149-158 105. G. Knieps: Aktuelle Vorschläge zur Preisregulierung natürlicher Monopole, erschienen in: K.-H. Hartwig, A. Knorr (Hrsg.), Neuere Entwicklungen in der Infrastrukturpolitik, Beiträge aus dem Institut für Verkehrswissenschaft an der Universität Münster, Heft 157, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 2005, S. 305-320 106. G. Aberle: Zukünftige Entwicklung des Güterverkehrs: Sind Sättigungsgrenzen erkennbar? Februar 2005 107. G. Knieps: Versorgungssicherheit und Universaldienste in Netzen: Wettbewerb mit Nebenbedingungen? erschienen in: Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Verkehrswissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft: Versorgungssicherheit und Grundversorgung in offenen Netzen, Reihe B, B 285, 2005, S. 11-25 108. H.-J. Weiß: Die Potenziale des Deprival Value-Konzepts zur entscheidungsorientierten Bewertung von Kapital in liberalisierten Netzindustrien, Juni 2005 109. G. Knieps: Telecommunications markets in the stranglehold of EU regulation: On the need for a disaggregated regulatory contract, erschienen in: Journal of Network Industries, Vol. 6, 2005, S. 75-93 110. H.-J. Weiß: Die Probleme des ÖPNV aus netzökonomischer Sicht, erschienen in: Lasch, Rainer/Lemke, Arne (Hrsg.), Wege zu einem zukunftsträchtigen ÖPNV: Rahmenbedingungen und Strategien im Spannungsfeld von Markt und Politik, Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, 2006, S. 119-147 111. G. Knieps: Die LKW-Maut und die drei Grundprobleme der Verkehrsinfrastrukturpolitik, erschienen in: Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Verkehrswissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft: Die LKW-Maut als erster Schritt in eine neue Verkehrsinfrastrukturpolitik, Reihe B, B 292, 2006, S. 56-72 112. C.B. Blankart, G. Knieps, P. Zenhäusern: Regulation of New Markets in Telecommunications? Market dynamics and shrinking monopolistic bottlenecks, Paper presented at the 17th European Regional ITS Conference, August 22-24, 2006, in Amsterdam; revised version: January 2007