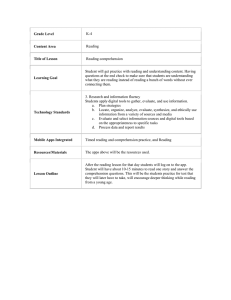

Vocabulary and Word Study to Increase Comprehension in Content

advertisement