Draft: Please do not cite or circulate without permission. 1

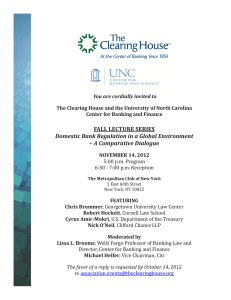

advertisement