Mushrooms of Toronto

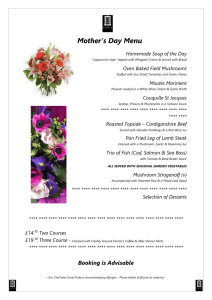

advertisement