PAPUA NEW GUINEA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

CONTENTS

I.

General Characteristics

1.1 Introduction

1.2 A Brief History

1.3 The Bougainville Secession

1.4 The Law and Order Dilemma

1.5 A Review of Current Conditions

II.

Macroeconomic Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 A Macroeconomic Appraisal:

GDP & Its Components

2.3 Fiscal Management

2.4 Monetary Policy

2.5 PNG’s External Accounts

2.6 PNG’s Debt and Payments

8

13

III. Economy by Sector

3.1 Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

3.1.1 Forests and Forest Resources

3.2 Oil and Minerals

3.2.1 Oil & Minerals and Economic

Development

3.3 Manufacturing, Construction and Power

3.4 Commerce, Transport and Financial Services

3.5 Services

18

IV.

23

What Lies Ahead

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was written by Wali M. Osman, with grateful

acknowledgment to the following: Bank of Papua New

Guinea, US Embassy, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Chamber of Manufacturers, Papua New Guinea Forest

Industries Association, Inc., Institute of National Affairs,

Investment Promotion Authority, Department of Lands,

PNG Chamber of Mines and Petroleum, Australian High

Commission, and especially Bank of Hawaii (PNG) Ltd.,

and a number of business and public leaders for their

insight and assistance.

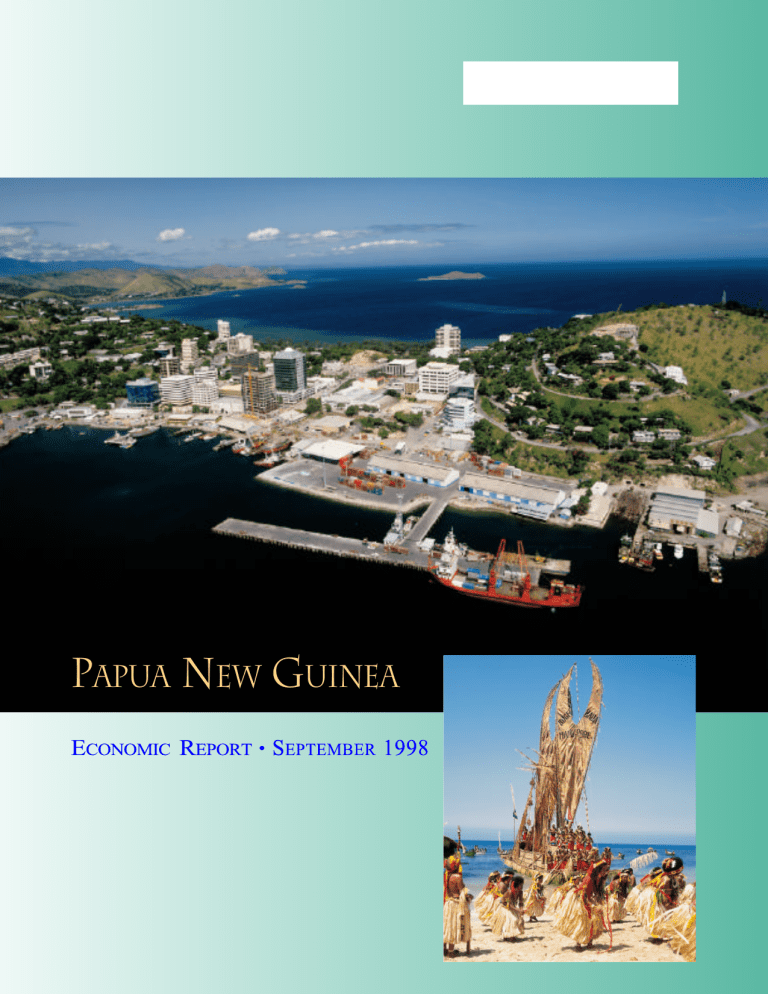

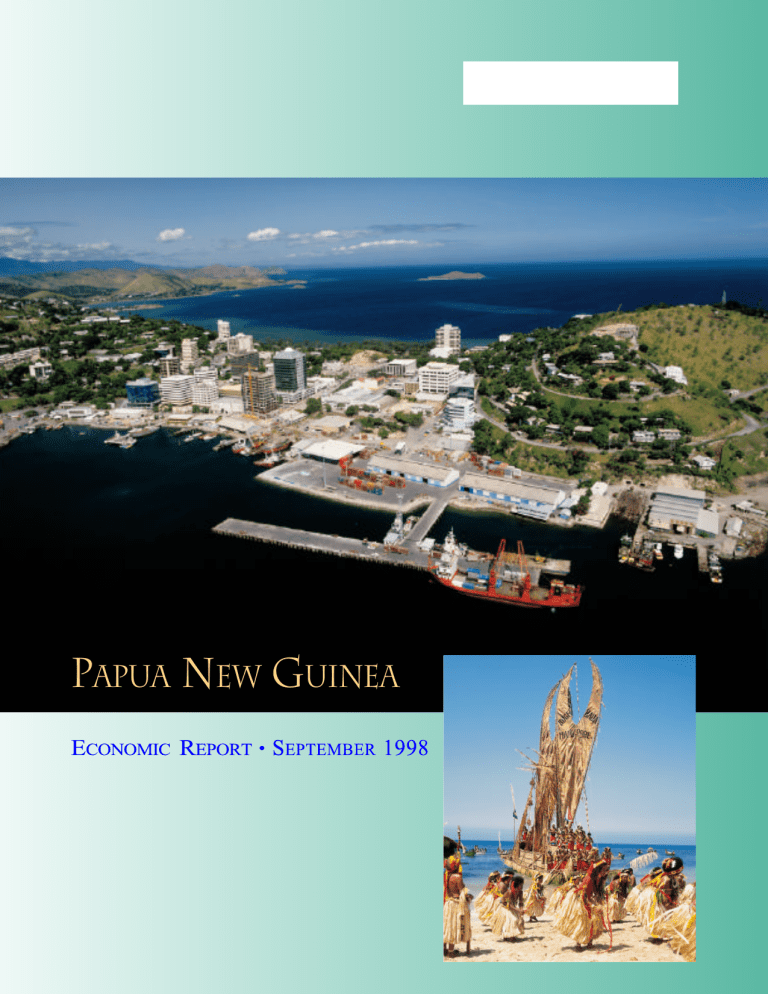

Cover Photos: Aerial view of Port Moresby, Papua New

Guinea, Rocky Roe, Rocky Roe Photographics, Papua

New Guinea

In-Text Photos: Rocky Roe, Rocky Roe Photographics,

Papua New Guinea

©1998 Bank of Hawaii. All rights reserved.

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

TO OUR FRIENDS AND ASSOCIATES:

Lawrence M. Johnson

Richard J. Dahl

We are pleased to present our first report on the economy of Papua New Guinea, a study of current

conditions and an analysis of factors that will shape the economic future of this South Pacific nation.

Bank of Hawaii established a presence in Papua New Guinea in March 1997, with the acquisition of the

former Indosuez Niugini Bank Ltd., now known as Bank of Hawaii (PNG) Ltd. With branches in Port Moresby

and Lea, Bank of Hawaii is positioned to offer a full range of quality financial services to the people and

businesses of PNG, just as we do in the South Pacific economies of Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia,

Vanuatu, Solomon Islands and elsewhere throughout the Pacific region.

Papua New Guinea is endowed with abundant resources and holds great promise. As the 21st century,

the Pacific century, unfolds we believe PNG has the potential to become a regional economy. We at Bank of

Hawaii look forward to playing a part in the growth and development of this promising economy.

We offer this report as a resource to those who share our interest in and commitment to the Pacific

region. We invite you to visit the Bank of Hawaii web site at <www.boh.com> to view reports on other Pacific

economies and to contact any Bank of Hawaii branch to learn more about our full range of financial services.

Sincerely,

Lawrence M. Johnson

Chairman and CEO

Richard J. Dahl

President and COO

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

Dotted lines group islands under the

same political jurisdiction. Unbroken

lines denote cultural affiliations.

Adapted from The Pacific Islands, 1992, courtesy of the East-West Center’s Pacific Islands Development Center

and the Hawai’i Geographic Society.

2

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

DISTANCE FROM

Australia: 1,200 miles

Honolulu: 4,100 miles

Los Angeles: 6,600 miles

CURRENCY

1997 exchange rate: 1.433 Kina per US dollar

ECONOMY

Income sources: agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining,

manufacturing

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1997: K6,108.4 million

US$4,260.6 million

LAND AREA

Total islands: over 600

Total land area: 465,000 square kilometers

(179,490 square miles)

Largest island: New Guinea

Capital: Port Moresby

POLITICAL STATUS

Parliamentary Democracy

POPULATION

1997 estimate: 4.23 million

1990-97 growth rate: 1.9 percent a year

Average life expectancy: 57 years

Reprinted from AusAID, Economic Survey of Papua New Guinea, August 1997

3

PACIFIC ISLANDS FACT SHEET

US DOLLAR-DENOMINATED ECONOMIES

Capital/

Distance

from

(miles)

Agana/

Honolulu 3,800

Tokyo 1,600

153,700

Land Area

(square

miles)

212

Notable

Geographic

Characteristics

One island. Major US naval

base and regional transshipment center at Apra

Harbor. In hurricane path.

COMMONWEALTH

OF THE

NORTHERN

MARIANA ISLANDS

(CNMI)

63,000

177

Saipan the largest island,

Tinian and Rota next,

14 others in the chain.

125 miles north of Guam.

US territory closest to Asia.

Garapan,

Saipan/

Honolulu 3,700

Tokyo 1,500

US dollar

FEDERATED

STATES

OF

MICRONESIA (FSM)

105,506

270

607 islands and atolls,

Pohnpei 130 square miles,

other major islands Kosrae,

Yap and Chuuk. The 4 FSM

states span 1,700 miles from

east to west.

Kolonia,

Pohnpei/

Honolulu 3,100

Hong Kong 3,100

US dollar

REPUBLIC

OF

PALAU

18,146

170

343 islands, the main group

encircled by a hundred mile

reef. Babeldaob 136 square

miles. 8 other inhabited

islands. Rock Islands.

Koror/

Honolulu 4,600

Tokyo 2,000

Hong Kong 1,700

US dollar

REPUBLIC

OF THE

MARSHALL

ISLANDS (RMI)

62,924

70

34 coral islands, 870 reefs,

highest elevation 33 feet

above sea level, average

elevation 7 feet.

Majuro/

Honolulu 2,300

Guam 1,800

US dollar

AMERICAN

SAMOA

58,900

76

5 islands, 2 atolls.

Pago Pago Harbor.

Home of newest US national

park. In hurricane path.

Pago Pago,

Tutuila/

Honolulu 2,600

Los Angeles 4,800

US dollar

462,176

975

130 islands, mostly atolls

in 5 archipelagoes. Tahiti

the largest island, 400

miles square, maximum

elevation 7,464 feet.

Main island, Grande Terre

250 miles by 30 miles (larger

than the Hawaiian Islands

together), mostly mountainous.

Several small islands.

Papeete, Tahiti/

Honolulu 2,700

Los Angeles 4,100

Paris 10,400

Tokyo 5,900

Noumea/

Honolulu 3,900

Paris 10,400

Brisbane 900

French

Pacific

franc

(F CFP)

2 main islands, highest

elevation 2,493 feet.

Wallis Island/

Honolulu 2,700

Paris 10,000

French

Pacific

franc

Eastern half of the island of

New Guinea. Largest by far

Pacific island-state land mass.

Other main islands New

Ireland, New Britain and

Bougainville.

Port Moresby/

Honolulu 4,300

Cape York,

Australia 300

Tokyo 3,100

Hong Kong 3,100

Kina

Population

GUAM

TOTAL/AVERAGE

Currency

US dollar

NON-DOLLAR ECONOMIES

FRENCH

POLYNESIA

220,524

1,609

NEW

CALEDONIA

196,836

7,376

WALLIS

AND

FUTUNA

14,800

106

PAPUA

NEW

GUINEA

(PNG)

4,150,000

179,490

4

French

Pacific

franc

GDP

(US$

million

current)

3,109.0

Per

Capita

GDP

(US$)

20,228

English,

Chamorro,

Carolinian

650.6

10,327

Tourism,

garment

manufacturing,

trade and

services

English,

8 major

local

languages

215.8

2,045

US payments,

government

services,

fisheries,

tourism

English,

Palauan,

SonsoroleseTobian

159.8

8,806

US Compact

payments,

tourism

English,

Marshallese

dialects

102.1

1,623

US payments,

Kwajalein Missile

Range, government services,

copra, fisheries

English,

Samoan

253.0

4,295

Tuna canneries,

government

services, remittances from

Samoans overseas

4,490.3

9,716

French,

Tahitian

3,655.8

16,578

Payments from

Metropolitan

France, tourism,

Tahitian pearls

French,

30 Kanak

dialects

3,717.5

18,886

25.0

1,689

Payments from

Metropolitan

France, nickel,

agriculture and

ranching, tourism,

aquaculture

French transfer

payments,

trochus shells

4,957.0

1,194

Major

Languages

English,

Chamorro,

also Tagalog,

Japanese

French,

East Uvean,

East Futunan

English,

Tok Pigin,

Hiri Motu,

hundreds of

vernaculars

Major

Income

Sources

Tourism,

military,

trade and

services

Political

Status

US territory since 1898.

Guam Organic Act of 1950

conferred US citizenship.

Some push for commonwealth status.

After WWI under Japanese

mandate. In 1947 became

part of US Trust Territory of

the Pacific. Since 1978 a

Commonwealth of the US.

Islanders are US citizens.

After WWI under Japanese

mandate. In 1947 became

part of US Trust Territory.

Became sovereign in 1979.

In compact of free association with US as of 1986.

After WWI under Japanese

mandate. In 1947 became

part of US Trust Territory.

Became sovereign in 1994,

in compact of free association as of 1994. Compact

ends 2044.

After WWI under Japanese

mandate. In 1947 became

part of US Trust Territory.

Became sovereign in 1979.

In compact of free association since 1986.

US territory since 1899.

Samoans are US nationals.

French controlled from the

19th century. Overseas

territory of France since

1957. Active independence

movement.

1853 became a French

possession. Overseas

territory of France since

1946. Relation to France

under review.

French controlled from

the 19th century. Overseas

territory of France since

1961.

Under Australian & German

control before WWI. Administered by Australia after WWII.

Independent within the British

Commonwealth since 1975.

The Bougainville secessionist

movement ended by a formal

treaty in April 1998.

Minerals,

oil and gas,

forestry,

agriculture,

tourism

5

Major

Sources

of External

Investment

US,

Japan,

Korea

Major

Sources

of Future

Income

Tourism,

services

Japan,

Korea,

Hong Kong,

US

Tourism,

services

US,

Japan

Compact

status uncertain as

of 2001.

Fisheries

development,

tourism

Compact

money,

tourism

Japan,

US

US,

Japan

US

US military.

Compact

status uncertain as

of 2001.

Fisheries.

Canneries,

remittances,

US

entitlements

Metropolitan

France

French

transfers,

tourism,

pearls

Metropolitan

France

French

transfers,

nickel,

tourism,

agriculture,

aquaculture

French

transfers

Metropolitan

France

Australia,

UK

Minerals, oil,

timber,

fisheries,

tourism

PACIFIC ISLANDS FACT SHEET (continued)

Population

COOK

ISLANDS

19,600

Land Area

(square

miles)

92

SAMOA

170,000

1,158

FIJI

815,045

7,055

82,400

266

393,000

11,197

99,000

386

185,000

4,707

11,200

8

NIUE

2,500

101

TOKELAU

1,800

4

10,200

10

TOTAL/AVERAGE

6,371,905

213,565

GRAND TOTAL/AVERAGE

6,834,081

214,540

HAWAII

1,205,126

6,423

KIRIBATI

SOLOMON

ISLANDS

TONGA

VANUATU

NAURU

TUVALU

Notable

Geographic

Characteristics

15 widely dispersed islands

including volcanic peaks and

atolls. Rarotonga the largest

island 26 miles square. In

hurricane path.

4 inhabited islands, 5

uninhabited. Highest point

6,100 feet, Mt. Silisili on

Savai‘i. In hurricane path.

320 islands. Viti Levu 4,000

miles square, Vanua Levu

2,100 miles square. Major

islands are mountainous

and forested to windward.

33 islands scattered 2,400

miles east to west, 1,300 miles

north to south. Almost entirely

low-lying atolls, Christmas

Island the largest.

850 mile long double island

chain. 6 mountainous main

islands, Guadalcanal 2,080

miles square.

Main islands volcanic,

some 150 coral atolls,

36 permanently inhabited.

80 scattered islands, several

active volcanoes. Largest

island Espiritu Santo 1,500

miles square, highest point

6,158 feet.

A single island with a 100

foot high central plateau of

now nearly exhausted phosphate-bearing rock.

Coral island rising 65 feet

from the ocean and another

130 feet to a central plateau.

3 atolls with islets 10 to 16

feet above sea level.

In hurricane path.

Capital/

Distance

from

(miles)

Rarotonga/

Honolulu 3,000

Wellington 2,000

Currency

New

Zealand

dollar

Apia/

Honolulu 2,600

Suva 700

Brisbane 2,500

Tala

Suva/

Honolulu 3,100

Sydney 2,000

Tokyo 4,500

Fiji

dollar

Tarawa/

Honolulu 1,300

Tokyo 3,900

Australian

dollar

Honiara,

Guadalcanal/

Honolulu 3,960

Port Moresby 900

Nukualofa/

Honolulu 3,100

Brisbane 2,000

Port Vila, Efate/

Honolulu 3,500

Tokyo 4,100

Solomon

Island

dollar

Nauru/

Honolulu 2,800

Banaba, Kiribati

200

Alofi/

Wellington 1,800

Suva 800

Nukunonu/

Honolulu 2,300

Wellington 3,800

Australian

dollar

Pa‘anga

Vatu

New

Zealand

dollar

New

Zealand

dollar

5 atolls, 4 coral islands,

maximum elevation 16 feet

above sea level.

Funafuti/

Suva 700

Sydney 2,500

Australian

dollar

4 main islands. Island of

Hawaii 4,028 miles square,

highest point of Mauna Kea

13,796 feet. Mauna Loa and

Kilauea on Hawaii both active

volcanoes. Maui 727 miles

square, Oahu 597 (Waikiki),

Kauai 552. In hurricane path.

Honolulu/

San Francisco

2,400

Los Angeles 2,600

Washington 4,800

Tokyo 2,500

US dollar

SOURCES: Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, 1994; Norman and Ngaire Douglas, editors, Pacific Islands Yearbook, 17th edition,

Suva, 1994; Europa, The Far East and Australasia, 1994; Gary L. Fitzpatrick and Marilyn J. Medlin, Direct-line Distances, International Edition,

New Jersey, 1986; International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics, June 1996; David Stanley, Micronesia Handbook, Chico,

California, 1989; David Stanley, South Pacific Handbook, 5th Edition, Chico, California, 1993; State of Hawaii Department of Business and

6

GDP

(US$

million

current)

50.9

Per

Capita

GDP

(US$)

2,596

English,

Samoan

170.0

1,000

Agriculture,

remittances from

abroad, tourism,

manufacturing

English,

Fijian,

Hindi

2,148.9

2,637

54.6

662

Sugar and other

agriculture,

tourism, forestry,

fishing, mining,

garment industry

Agriculture

(copra),

remittances,

aid

English, Solomon

Islands Pijin,

more than 80

vernaculars

Tongan

343.7

875

124.9

1,262

French,

English,

Bislama

247.0

1,335

English,

Nauruan

80.7

7,205

English,

Niuean

7.1

2,825

English,

Tokelauan

1.2

667

English,

Tuvaluan

3.8

373

15,588.0

2,446

Major

Languages

English,

Cook Islands

Maori

English,

Micronesian

English

20,078.3

2,938

35,146.4

29,164

Major

Income

Sources

Government

aid, services,

tourism

Political

Status

Self-governing since 1965

in association with New

Zealand. Cook Islanders

are citizens of both Cook

Islands and New Zealand.

Under German control before

WWI, New Zealand after.

New Zealand trusteeship

after WWII. Independent

since 1962.

Annexed by Great Britain in

1874. Became independent

within the Commonwealth

in 1970, rejoined the

Commonwealth in 1997.

Annexed by Britain in 1919.

A republic within the British

Commonwealth since 1979.

Agriculture,

timber sales,

fishing and fish

canneries, aid

Agriculture,

tourism

Major

Sources

of External

Investment

New

Zealand

Major

Sources

of Future

Income

Tourism

New

Zealand,

Japan

Agriculture,

tourism,

light

manufacturing

Agriculture,

tourism,

mining, light

manufacturing

Fisheries

development

Australia,

New

Zealand,

EU,

Japan

NA

Agriculture and

ranching, tourism, Offshore

Finance Center,

services

Phosphates and

investments

from

phosphates

Subsistence

activity,

government aid

Subsistence

activity,

government aid

British protectorate as of

1873. Politically independent

within the Commonwealth

since 1978.

British protectorate as of

1900. Independent monarchy

within the Commonwealth.

Anglo-French New Hebrides

Condominium in 1906.

Republic of Vanuatu within

the British Commonwealth

established in 1980.

From 1919 administered by

Australia. Became an

independent republic in

1968.

Self-governing since 1974

in free association with

New Zealand.

Non-self-governing territory

administered by New

Zealand beginning 1925.

Australia,

Japan

Agriculture,

fisheries,

tourism

NA

Tourism,

agriculture

Australia,

Japan

Tourism,

agriculture

NA

Investments

from

phosphate

NA

Tourism

NA

Subsistence

activities,

government

aid

Subsistence

activities,

government

aid

Subsistence

activity,

government aid

Independent state within

British Commonwealth

since 1978.

NA

Tourism,

services,

trade,

government

Annexed in 1898, became

a US territory in 1900,

became a state in 1959.

US,

Japan,

Australia

Tourism,

defense,

services,

trade,

government

Economic Development, Data Book 1995, Honolulu, 1996; Peter W. Thomson, Trade and Investment in the South Pacific Islands, Honolulu, 1989;

World Bank, World Development Report, 1996; various Bank of Hawaii economic reports, 1992–97, and other sources. (Rev. 4/22/98)

For further information, contact Bank of Hawaii Regional Economist Wali M. Osman

at 808-537-8349 (phone), 808-536-9433 (fax) or wmosman@boh.com (e-mail).

7

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

I. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

1.1 INTRODUCTION

of just over $800. PNG’s GDPfell from an estimated US

$5 billion in the mid-1990s mainly due to the effects of

recent exchange rate fluctuations. Its current per capita

GDP (in US dollars) places PNG in the bottom 12 percent

of the 40 economies classified by the World Bank as

middle-income economies whose per capita GDPranges

from $770 to $2,900. PNG is in the same per capita GDP

category as Bolivia, Macedonia, Indonesia and the

Philippines.

In recent years, as many as 30,000-35,000 expatriates,

mostly Australians, have lived in PNG to advise its

government and businesses in their efforts to modernize

PNG and achieve higher standards of living. Although

relatively well endowed with land, minerals and a large

exclusive economic zone, PNG’s economy has grown

slowly and developed erratically after independence in 1975.

Observers expected more rapid and consistent

economic growth because, theoretically, a large land mass

rich in minerals and natural resources plus a relatively small

population is an ideal combination for rapid economic

growth. Such a mix is rare in developing regions, especially

the Pacific. However, despite this abundance of land,

mineral and ocean resources, without adequate skilled labor

and an institutional structure essential to an efficient market

economy, PNG could not produce sustained economic

prosperity.

Domestic strife, especially the secessionist rebellion

in Bougainville that started in 1988 and did not formally

end until April 1998, contributed to PNG’s inconsistent

economic growth. However, closure of the Bougainville

Copper Mine in 1989 did not lead to production cutbacks in

overall mining and oil output as expected. In fact, mining

and oil production increased from other sources in the

1990s to make up for the loss of the Bougainville

production.

PNG’s sometimes rapid growth in GDP, though

inconsistent, was barely sufficient to keep real per capita

GDP (averaging 2.2 percent in 1990-97) in pace with

population growth (averaging 1.9 percent in 1990-97).

PNG has been one of the few Pacific economies in the

1990s to do so, suggesting no erosion in real purchasing

power. However, given PNG’s much larger population and

resources compared to other Pacific islands, this performance

is below its long-term potential output level.

As the Asian economic and financial turmoil of the

past 12-15 months subsides, and some of the area’s major

economies resume normal production and distribution

activities in the months ahead, PNG must begin adopting

institutional and market reforms that would make it a more

open and efficient economy. PNG is in a far better position

The independent nation of Papua New Guinea

(PNG) is one of the South Pacific’s largest island countries.

Comprised of some 600 islands, atolls and coral reefs with

a total land area of 465,000 square kilometers (179,490

square miles), PNG is 15 percent larger than California and

nearly 28 times the land area of Hawaii.

The Island of New Guinea, whose western half is the

Indonesian province of Irian Jaya, accounts for over 80

percent of PNG’s total land area, and is the world’s second

largest island after Greenland. Smaller islands include the

Bismarck Archipelago (mainly New Britain, New Ireland

and Manus) and the northern part of the Solomon Islands

(mainly Bougainville and Buka). PNG’s climate is

consistently hot and humid throughout the year, with

average temperatures ranging from 22 degrees C (72 degrees

F) to 33 degrees C (91 degrees F).

Of the 700 languages spoken in PNG, Melanesian

Pidgin and Hiri Motu are the two most widely used,

especially in urban areas such as Port Moresby, the capital.

English, however, is the language of business and

government. PNG is widely influenced by Australia due

to decades of close political, economic and business ties.

Australia provides PNG the bulk of its foreign economic

assistance, and is among its major trading partners and

sources of both physical and human capital.

Although more than half of its population is illiterate

and only a fraction of the literate population has primary or

high school education, PNG is a functioning democracy.

Thus an open dialogue on national priorities for economic

development is feasible. The number of skilled PNG

citizens, though growing rapidly, is small. It is not keeping

pace with the demand for skilled labor, which is rising even

more rapidly. Currently, PNG is last among all Pacific

economies, in terms of most social and economic

indicators. Life expectancy at birth is 57 years, one of the

lowest in the South Pacific.

In 1997, PNG had an estimated population of 4.23

million, mainly Melanesians. In 1990-97 PNG’s population

grew from 3.70 million to 4.23 million, with an average

growth rate of 1.9 percent annually. These gains are

moderate in comparison to other Pacific Island economies

where population growth rates of 3-4 percent are normal. If

PNG maintains a moderate population growth rate of less

than two percent annually, it can easily attain a higher

standard of living once its resources are put to more

productive uses.

PNG generates a total gross domestic product (GDP)

of about US $3.5 billion a year, yielding a per capita GDP

8

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

than any other developing economy in the Pacific

to achieve a consistently higher standard of living

because of its many positive characteristics.

Market demand already exists for most of its

products, especially minerals and energy.

Settlement of the Bougainville conflict, signed

into a binding treaty in late April this year, is a

major step toward reconciliation, putting PNG

back on track to growth and prosperity. The PNG

government and commerce can now concentrate

on economic development.

1.2 ABRIEFHISTORY

Newer methods of identification, dating

and analysis of historic patterns of human

settlement in conjunction with new archeological

findings in PNG may better determine the date of

the earliest human occupation in that part of the

world. However, existing evidence suggests that

PNG is among the oldest societies in the world.

Human occupation evidently began some 45,00050,000 years ago on the Huon Peninsula on the

north coast of the main island. The first settlers

are believed to have arrived from Southeast Asia

in small numbers “involuntarily” because their

watercraft, which were mostly solid logs and

bamboo rafts, are considered too primitive to have

been chosen for deliberate crossing.1

Since the earlier indigenous people of PNG

lived in societies without written script, accurately

Native Papua New Guinean wearing a traditional, colorful headdress

establishing all social, political and economic

links hinges on the results of current archeological

efforts in combination with other physical

The earliest evidence of gardening in PNG dates

evidence.

back some 9,000 years at Kuk, near Mount Hagen in the

The earliest settlers were hunters, fishers and

Western Highlands, making the highlanders among the

gatherers of wild plants. There is no clear understanding of

world’s earliest gardeners.

what food plants and animals were native to the area, and

Ancestors of present-day PNG inhabitants may also

which were later introduced from the outside world.

be among the earliest traders and seafarers, as there is

Important food plants at the time of European contact in the

evidence of trade with areas as far west as Southeast Asia

early 16th century were sago palm, taro, yams, cassava,

and as far east as New Caledonia, plus an exchange system

sweet potato, breadfruit, coconuts, bananas and green leafy

in practice, all tracing back 4,000 years. Apart from the

vegetables. Animals present in PNG at that time include

early signs of trade in bronze and obsidian between

wallabies, snakes, crocodiles, pigs, dogs, fish, birds and

Southeast Asia and parts of today’s PNG some 3,000 years

insects. Among animals to have been introduced to PNG

ago, there is little evidence of contact between PNG and

following contact with the outside world are domesticated

that region before the 19th century. However, there is

chickens, pigs and dogs.

reasonable likelihood that trade between Indonesia and the

1

John Dademo Waiko, AShort History of Papua New Guinea, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 2.

9

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

western half of the Island of New Guinea existed as far

Following the Australian (British) model, PNG

back as the 13th century. There is also the likelihood that

is a parliamentary democracy. The House of Assembly,

before the arrival of the first Europeans, some coastal

renamed the National Parliament when PNG became

people from today’s PNG were captured by Asian raiding

independent, was first formed in 1972. Given the many

parties for sale as slaves. However, no new settlements

diverse ethnic and linguistic groups that make up the

were established and the contacts between New Guinea and

people of PNG, a functioning representative democracy is

Southeast Asians ended when Europeans arrived and

practically the only optimal political model that can keep its

colonized the area.

economy from fragmentation.

Available sources indicate that at the time of first

The diversity of interests inherent in numerous

European contact, the 700 or so different languages of the

ethnic and linguistic groups, especially in a developing

peoples that today make up the PNG nation already existed.

economy where political and market institutions are

These languages represent the many different communities

evolving, however, sometimes makes it difficult to establish

that lived in isolation from each other until recent times.

a strong and decisive central government. But as is evident

Thus PNG’s present communication challenges and

elsewhere, better education and more mature social,

structural fragmentation can be traced back to this early

political and economic institutions can pave the way for a

period.

stronger democracy with a dynamic market system.

PNG was first visited by European navigators in the

early 16th century but explorations and colonial settlement

1.3 THE BOUGAINVILLE SECESSION

did not occur until mid-19th century. In 1884, the northern

part of eastern New Guinea came under German

Political instability of some degree arising from

administration and later became known as German New

ethnic, linguistic and territorial differences existed long

Guinea. In 1914, Australian troops removed the Germans

before independence in 1975. With political independence,

from the territory and Australia subsequently ruled the area

PNG also inherited from Australia a centralized and

under a League of Nations mandate until 1942, when much

bureaucratic federal government in Port Moresby. In some

of it fell under Japanese occupation. In 1945, the territory

instances citizens and governments in provinces felt they

returned to Australian rule under a UN trusteeship.

did not receive their fair shares of income and wealth from

The western half of New Guinea was a part of the

the central government. This sense of inequity, whether

Netherlands East Indies until 1949 and from 1949 to 1962

influenced by ethnic or linguistic differences, led to the

was known as the Netherlands Nieuw Guinea. In 1963,

rebellion in Bougainville that started in 1988.

after military action by

Indonesia, it became its

province of Irian Jaya. The

southern part of eastern New

Guinea became British New

Guinea in 1906, following

the establishment of a British

protectorate in 1884 and

annexation in 1886.

Australia administered what

became the Territory of

Papua New Guinea until

1949 when it was joined with

the Trust Territory of New

Guinea. In December 1973,

the Territory of Papua New

Guinea became internally

self-governing and on

September 16, 1975 became

the independent nation of

A mining facility located at Porgera, Enga province

Papua New Guinea.

10

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

In April 1988, landowners on Bougainville submitted

compensation claims for more than was being paid by the

Bougainville Copper Limited at Panguna, which had

been mining since 1972. With no additional payments

forthcoming, a group of citizens calling itself the

Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) committed acts

of sabotage in late 1988, sparking the beginning of the

secessionist movement.

The rebels demanded both higher payments for the

copper mined on the island, and independence from PNG

for the North Solomons Province, of which the Island of

Bougainville is a major part. With violence escalating,

mining activity practically came to a halt in 1989-90. For

most of the 1990s, the Bougainville conflict was among the

few globally known continuing hostilities. It paralyzed

Bougainville’s economy and later destroyed most of the

island’s infrastructure, including schools.

With violence escalating and no victory in sight for

either the BRAor the PNG government, they finally opted

for reconciliation through talks sponsored by New Zealand

in 1997. The 500 miles between Port Moresby and

Bougainville made both war and peace harder. While

hostilities have ended, this reconciliation does not

guarantee that other parts of PNG may not also rise against

the central government, especially if there is a continuing

perception that the provinces do not receive their fair shares

of national income and wealth.

It was not until the Bougainville rebellion that PNG’s

integrity as a nation came into question. However, to the

PNG government’s credit, the uprising did not spread to

other parts of the country as might have been expected,

given the country’s ethnic diversity and dispersed island

landscape. The BRAachieved nothing more than keeping

the conflict current in regional and global news for a

decade.

The details of rebuilding the Bougainville economy

and subsequent political and economic arrangements are to

be worked out over the months and years ahead. Major

unanswered issues include Bougainville’s desire for more

autonomy, resumption of gold and copper production,

revenue allocation and, finally, the cost of rebuilding the

severely damaged Bougainville economy.

Settling the Bougainville conflict paves the way for

overall political and economic stability in PNG. Preventing

future rebellions, however, calls for a more active dialogue

between the federal and 19 provincial governments. Also,

more rapid economic growth that raises both the stock of

national wealth and the flow of national income can facilitate

a more equitable distribution of both, thereby further

diminishing the potential for economic and social conflicts.

The National Parliament recently passed laws that

encourage dialogues to address questions relating to more

equitable distribution of wealth and income, as well as other

provincial grievances. Meanwhile, as peace and stability,

better education and more contacts with the outside world

strengthen PNG’s political and market institutions, the

pressure on the central government to deliver major

development programs should lessen over time.

1.4 THE LAWAND ORDER (L&O) DILEMMA

Concurrent with the Bougainville conflict, crime in

the late 1980s and 1990s, especially in urban areas, also

became a major problem in PNG. In 1991, the National

Parliament passed a program of severe measures to combat

crime, including the introduction of the death penalty and

tattooing the foreheads of convicted criminals.

Still, crime and general disregard for law and order

(L&O) remain major concerns in urban areas, especially the

national capital district including Port Moresby. Random

violence in Port Moresby and other urban areas has, from

time to time, generated adverse publicity in both regional

and global media. Security is a growing component of total

cost for businesses and expatriate residents. In fact,

increased security costs is often cited by businesses to be

among the main disadvantages of doing business in PNG.

As in other multi-cultural societies, there are

different perceptions of crime and, therefore, different

implementations of law enforcement. Anecdotal reports

indicate that only three percent of criminal suspects are

indicted and less than half of them get convicted. In the

end, fewer than one percent receive punishment.

A1997 study showed that while the direct cost of the

L&O problem may be only three percent of total cost,

indirect cost is a much higher component of total business

cost. The study found that, “the indirect costs appear to be

several times higher than the direct costs.” 2

Direct L&O cost includes costs of security personnel

and equipment while indirect costs encompass constrained

markets and management time devoted to preventive and

remedial actions. Although generally effective, private

security has become a notable extra cost that businesses in

Institute of National Affairs, “Cost Structures in Papua New Guinea,” Discussion PaperNo. 69, SalPress, Boroko, NCD, Papua

New Guinea, April 1997, p. 1.

2

11

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

PNG must bear, aside from other costs and constraints

imposed by either institutional or market factors.

Another recent study of known criminal activity

sheds additional light on the extent of the L&O problem in

urban areas. Based on a 1995 survey, over 32,000 persons

in urban centers depended “on crime as their main source

of income, representing 14.8 percent of the urban work

force.”3 The study found that the earnings of criminals did

not differ significantly from the relatively high wages of

unskilled labor in the formal sector. Although this study did

not find a correlation between urban unemployment (which

averaged 29.3 percent in 1995) and urban criminal activity,

such a correlation has been shown to exist in other markets.

Port Moresby’s crime problem will most likely

continue until rural migration to the city subsides, which

will happen only when more rural people have reason to

stay where they are. Aslowdown in rural-urban migration

and improvement in the job market can be achieved as the

country’s resources such as minerals, oil and gas are put to

higher and better uses. The crime problem will then

diminish but may not disappear. With improvements in the

job markets, the L&O concern in PNG may subside to the

levels of other urban areas of similar size in the region.

Despite the L&O problem, most businesses were

expanding until the Asian crisis ensued. The central

government has indicated its commitment to dealing

with the L&O problem, but like governments in other

democracies, it cannot focus on it at the expense of other

major concerns. The government will not eradicate the

L&O problem any time soon. However, its commitment to

dealing with the problem is a major first step in restoring a

measure of safety and security to PNG’s cities.

because of rapid migration to the cities. PNG’s resources,

mainly oil, gas and other minerals, fish and forests will help

pay for urbanization of cities and towns scattered all over

this largely inaccessible country. In the years ahead, tourism

will become an increasingly important sector. The full

impact of the Asian crisis and devaluation is not known, but

it has destabilized the economy and disrupted production

and distribution activities throughout the country.

Further damage to the economy has been inflicted by

tropical storms and the 1997 drought attributed to El Nino.

Among those things affected by the drought was copra

export, which dropped 9.0 percent to 90,300 tons. In

addition, a storm in early 1997 severely impaired cocoa

production in the East New Britain Province. Total cocoa

exports through December 1997 amounted to 36,700 tons,

down 10.5 percent from the previous year. Also affected

was coffee production and exports, which fell 5.6 percent

below 1996 levels to 58,000 tons.

The total export of logs, which amounted to 2.4

million tons in 1997, was also down 8.9 percent from the

previous year. But unlike other agricultural exports that

were affected by natural disasters, the fall in log exports

was entirely due to weak demand in Asia, the main market

for South Pacific hardwood logs. Further problems in Asia,

especially in Japan starting late in 1997, have caused

substantial declines in both export quantities and prices of

logs. The economic recession has gradually worsened since

the middle of this year.

In mid-July a tidal wave (tsunami) that hit the north

central coast of the main island added to the ongoing

economic problems. Occurring without warning, the tidal

wave wiped out a number of villages along the coast,

causing several thousand deaths. Due to the large number

of human casualties and severe economic loss in the area, it

will be some time before a sense of normalcy returns to that

coastal region.

Growing, although modestly, in the midst of these

declines was palm oil. Exports through December

amounted to 274,000 tons, up 3.0 percent from 1996. Palm

oil is now approaching the level of coffee in terms of market

value of exports. With global demand for the versatile palm

oil rising, PNG, Solomon Islands and other South Pacific

producers stand to gain more market share as their high

quality oil is produced by relatively low-cost labor abundant

in these markets. Although total production costs (including

labor) in other producing areas such as the Philippines,

1.5 AREVIEW OFCURRENT CONDITIONS

With the Bougainville settlement and the World

Bank & IMF providing transitional (restructuring) aid, the

PNG economy will improve gradually but steadily in the

months and years ahead. Political, economic and business

conditions are now ideal for restoring confidence in the

economy and respect for law and order. There is no

alternative if the country is to take full advantage of its

resources and become self-sufficient.

PNG’s economy has been in recession since mid1997, mainly because of commodity price drops and

devaluation. However, business in urban areas is growing

3

Theodore Levantis, “Urban Unemployment in Papua New Guinea - It’s Criminal,” Pacific Economic Bulletin, National Centerfor

Development Studies, The Australian National University, Volume 12, Number 2, 1997, p. 73.

12

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

Malaysia and Indonesia may not be much higher, PNG’s

advantage lies in adopting newer production and extraction

methods and in opening up new markets such as Europe.

PNG’s economy is not flexible or mechanized enough

to increase exports of commodities rapidly, aside from oil

and minerals, at globally favorable prices. Most of PNG’s

exports, including oil, are commodities available in other

markets. At the same time, devaluation has raised import

prices, especially wages of ubiquitous expatriate labor, some

of which is critical to getting the economy back on track.

This unsettling period will last at least another 6-12 months

before the economy begins to recover and stability returns to

financial (currency) markets and exchange rates.

Although the end of the Bougainville conflict frees

the government to focus on rebuilding and revitalizing both

Bougainville and PNG as a whole, this formidable task will

take time. Re-opening the Bougainville mines to resume

gold and copper production may take months, possibly

years, as agreements still must be reached on revenue

allocation among landowners, national and provincial

governments. It was this issue that led to the protracted

conflict in the first place.

The PNG government is also under pressure by

business, investors, creditors and the large expatriate labor

force to deal effectively with infrastructure concerns. Lack

of adequate transport, educational facilities and other basic

infrastructure hampers PNG’s production and distribution

capacities. Coffee, for instance, is grown in some areas

without adequate transport links to markets. Even good

harvests will not translate to good income if the products do

not reach markets in a timely manner.

Anational economic summit convened in February by

the new coalition government, which came into power last

year, was a significant step toward a national economic

dialogue. It enabled the business community to make

recommendations about reconstruction and installation of a

consistent national political and economic management policy.

With the proper mix of institutional and market

reforms in place, PNG can generate a much higher standard

of living for its population than any other South Pacific

Island economy and in relatively shorter time.

PNG’s vast resources make setting a consistent

national economic growth goal of at least 10-percent a year

over several years feasible. Commercial ranching and

agriculture particularly hold large potentials for the country,

especially in tropical crops and fruits that may be exported

as fresh and processed products.

By the year 2000, once the Asian crisis has subsided,

expansion of mineral and oil production as main revenue

(foreign exchange) sources could set PNG on an accelerated

growth track. Logistically, however, growth in this market

will be more costly than in others because the main towns

and cities are so far apart from each other.

Some 15 million hectares of harvestable forests exist

in PNG, of which 4-5 million have been designated for cut.

Only about three million hectares have been cut to date,

some of which have already been replanted and sustainable

harvest begun.

Recent geological surveys indicate that PNG is

perhaps more of a gas reservoir than an oil one. Known

gas reserves are large, and more may be found. Under the

auspices of US-based Chevron which has a presence in

PNG, work on a $4-5 billion dollar gas pipeline to

Queensland is to start in the next 12 months. When

finished in 2001, the pipeline will carry natural gas from

PNG to Queensland.

Known petroleum reserves are modest, but large

ones may still exist. Avariety of minerals can be found

in varying quantities and concentrations underground in

PNG, and its 1.2 million square miles (3.1 million square

kilometers) of surrounding ocean may yield deposits of

undersea minerals, in addition to fish and other seafood.

During the first quarter of 1998, a local firm announced that

it had put together a financing package of US $600 million

to build a new tuna processing plant in an outer province.

Financing, according to media sources, would come from

European Union banks and the firm was confident of its

plan and financing.

Currently, PNG receives fewer than 60,000 visitors

a year, of whom about 20,000 are tourists. With fear of

violence receding, tourism holds vast potential for PNG,

mostly in areas outside Port Moresby. PNG has all the

aesthetic resources to make it a major tourist destination, for

leisure and business travelers, once the proper infrastructure

is in place. Its new airport terminal, which opened in

March, is a major asset in expanding tourism. The newer

section of the capital district (Waigani) on the mountain side

of downtown Port Moresby, is undergoing expansion. It will

supply much needed new commercial space.

II. MACROECONOMIC REVIEW

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Macroeconomic instability in PNG arises from two

main sources: (a) economic structure and its performance,

that is, the economy’s makeup and production and

distribution activities of goods and services, and (b) liquidity

13

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

problems arising from both internal and external conditions

that hamper government’s and business’s ability to meet

their financial needs. Internal liquidity problems impede

economic growth, but external liquidity dilemmas often

have far more serious implications, especially if imports

(export earnings) are critical to keeping the economy going.

As recent developments in Asia have shown, the

interdependence of the region’s economies on each other

has become a double-edged sword. During economic

booms, interdependence helps regional economies expand.

During an economic downturn, it exacerbates economic

contractions. An example of instability arising from PNG’s

economic structure is its reliance on exports of primary

commodities, including crude oil, which command low and

widely fluctuating prices in regional and global markets.

An example of liquidity risk arising from external

conditions, often beyond the control of national government

and markets, is the recent drop in commodity prices,

especially when coupled with devaluation caused by

regional and global economic forces. In fact, the adverse

impact of recent commodity price declines (contributing to

revenue loss) and devaluation (contributing to wage and

price inflation) has been so severe in PNG that it prompted

the World Bank and IMF to make special provisions in their

proposed structural adjustment loans.

Current and accurate information is unavailable on

most of the critical macroeconomic aspects of PNG in

terms of assessing its economic performance and prospects.

However, there is enough relevant information to make an

informed appraisal.

commodity price drops, devaluation caused by global and

regional conditions and weak global demand for

commodities already existing prior to recent price changes.

Just before the 1995-96 recession, real GDP growth

averaged 10.2 percent (1991-94), mainly because of gains

in minerals and petroleum production which commenced in

1992. According to the Australian Agency for International

Development (AusAid), oil exports started at K301 million

in 1992, rose to K818 million in 1993, but dropped to K703

in 1994, then rose back to K828 million in 1995 before

peaking at K1.074 billion in 1996.4

It is unlikely that PNG will realize its petroleum sales

goals in 1998 based on earlier price and quantity projections,

as oil prices dropped in recent months, reaching a low of

$13.4 a barrel in April. Though crude oil has been an

important part of export earnings since 1992, the recent drop

in price can only signal further erosion in export earnings.

At the same time, low energy prices may help PNG

fight inflation, which rose from 3.0 percent in 1994 to 17.0

percent in 1995. Although it dropped to 12.0 percent in

1996, PNG’s inflation in 1995-96 was one of the highest in

the Pacific. Amain factor contributing to price inflation in

the last few years in PNG has been devaluation of the Kina

that started in 1992 and continued through 1997. As

measured by official exchange rates, the Kina dropped 41.4

percent in 1992-97 against the US dollar.

While inflation may be a problem in the near term

and even mistaken for a false signal of surging aggregate

demand, another useful measure of economic performance

is employment. Employment and labor force data,

however, are sketchy for PNG. An employment index,

which the PNG Central Bank derives from a quarterly

employment survey of the private sector, is reported for the

economy and the various industries.

The index’s base year is 1989 (1989=100). As

measured by this index, employment in PNG in 1996 was

only slightly higher (0.5 percent) than 1989. In the interim,

the index was as low as 91.1 percent in 1991 and 91.4

percent in 1993 when real GDP, according to AusAid, rose

13.3 percent. The index rose to 98.1 percent of the 1989

average in 1994 while real GDPgain dropped to 4.1 percent.

In 1995, the index fell to 93.5 while real GDPdropped too

but only slightly (0.9 percent). As GDPsank another 5.0

percent in 1996, the employment index rose 7.5 percent to its

all-time high of 100.5 percent of the 1989 average.

As a lagging indicator, it is possible for employment to

2.2 AMACROECONOMIC APPRAISAL: GDP& ITS

COMPONENTS

In 1997, PNG generated a GDPof US $4.3 billion,

yielding a per capita GDP of US $1,008. These US dollar

GDP figures are consistent with other published ones, but

examining PNG’s GDPand other macroeconomic

quantities in Kina, its own currency, provides a more

realistic review of economic conditions and performance.

Real GDP(adjusted for inflation) peaked at K4.526

billion in 1994, dropping only slightly (0.9 percent) to

K4.486 billion in 1995 and another estimated 5.0 percent to

K4.261 billion in 1996. All indications are that the 1995-96

recession continued in 1997, and spilled over to 1998. The

main causes of economic decline in 1997-98 have been

4

Australian Agency forInternational Development (AusAid), Economic Survey of Papua New Guinea, Commonwealth of Australia,

August 1997, p. 171.

14

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

remain high while the economy is slowing down.

However, employment and total income growth

rates going in opposite directions for more than one

year is not customary. In 1990-96, real GDP and

employment growth rates crossed paths five times.

The likely explanation is that the employment

index does not reflect the extent of employment,

unemployment and underemployment, which is

common in the Pacific economies.

The country’s labor force (persons aged

15-64) numbers over two million. However,

only about 220,000 people work in the so-called

formal sector (those on formal payroll), of whom

about 60,000 work in the public sector. Thus,

payroll employment is available to only 10

percent of the labor force. The full extent of

Agricultural field

employment in the subsistence economy is not

known, except that 80-90 percent of PNG’s population

depends in one way or another on subsistence farming,

some of PNG’s other oil and mineral resources including

gathering and fishing. Given these parameters,

gold and copper from Bougainville may contribute to

employment data should be viewed cautiously.

export earnings.

As far as shifts in the makeup of GDPare concerned,

Agriculture, forestry and fishing have remained

a notable change occurred in 1990-96 with the start of oil

relatively stable as a share of GDP, averaging 27 percent in

production and export in 1992. It raised mining and

1990-96. This sector’s share, too, may increase with the

petroleum as a share of GDPfrom 21.9 percent in 1992 to

completion of a proposed fish cannery as well as other

28.1 in 1993 and 31.4 percent in 1995, but fell back to 26.3

seafood processing operations in PNG by 2001.

percent in 1996. Without production changes (resumption

Also reasonably stable as a share of GDPin 1990-96

of production in Bougainville or other new mines), mining

was construction and manufacturing at 15 percent, followed

and petroleum as a share of GDPmay range from 25.0 to

by commerce, transport and financial services averaging

30.0 percent (averaging 26.6 percent in 1992-96).

another 15 percent, and services, which averaged nearly 20

With the building of the natural gas pipeline

percent. Given this GDP makeup, instability arising from

proposed by Chevron to carry gas from PNG to

commodity price and exchange rate changes will be more

Queensland, the share of mining and petroleum will rise. It

serious, while those linked to structure will remain

is also reasonable to expect that between 1999 and 2001,

relatively straightforward.

2.3 FISCALMANAGEMENT

INDEXES OF FORMAL PRIVATE EMPLOYMENT

(JUNE 1989=100)

Formal private employment

Employment by industry

Retail

Wholesale

Manufacturing

Building and construction

Transport

Agriculture, forest and fishing

Financial and business

Mining

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995 1996

99

95

91

94

91

98

93

100

101

96

99

106

106

96

104

101

88

87

95

107

112

89

109

101

86

81

95

82

104

89

103

100

85

86

102

77

94

97

105

107

84

84

104

74

91

95

104

106

88

91

120

78

95

101

102

105

92

82

109

70

89

87

111

112

95

82

115

89

96

91

116

116

Source: AusAID, Economic Survey of Papua New Guinea, August 1997, p. 158

15

PNG’s fiscal management has been

questionable for most of this decade. The

country has had a fiscal deficit almost every

year during the 1990s. The deficit grew

rapidly in the early 1990s, reaching a record

K296 million in 1993. It dropped just as

rapidly, turning into a K37 million surplus in

1996, only to be followed by another deficit

in 1997.

As a share of GDP, PNG’s deficits

have been relatively small in comparison to

other developing economies, where public

infrastructure consumes large sums of

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

PNG ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL INDICATORS

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

Nominal GDP ($US million)

Nominal GDP Per Capita ($US)

3,219.6

870.2

3,787.7

1,004.7

4,378.0

1,137.1

5,030.8

1,283.4

5,383.9

1,346.0

4,809.1

1,181.6

4,957.2

1,195.3

4,260.6

1,008.2

3,479.8

808.0

Nominal GDP (Millions of Kina)

Nominal GDP Growth (%)

Nominal GDP Per Capita (K)

Real GDP (1990 Prices, K mill)

Real GDP Growth (%)

Real GDP Per Capita (K)

3,076.0

1.0

831.4

3,076.0

(3.0)

831.4

3,606.0

17.2

956.5

3,370.0

9.6

893.9

4,223.0

17.1

1,096.9

3,836.0

13.8

996.4

4,922.0

16.6

1,255.6

4,348.0

13.3

1,109.2

5,411.0

9.9

1,352.8

4,526.3

4.1

1,131.6

6,138.0

13.4

1,508.1

4,485.5

(0.9)

1,102.1

6,533.0

6.4

1,575.2

4,261.3

(5.0)

1,027.5

6,108.4

(6.5)

1,445.4

4,176.0

(2.0)

988.1

6,517.6

6.7

1,513.5

3,758.4

(10.0)

872.7

GDP by Expenditure (K mill)

Private Consumption

Government Consumption

Gross Fixed Investment

Exports of Goods & Services

Imports of Goods & Services

3,076.0

1,816.0

764.0

752.0

1,250.0

1,506.0

3,606.0

2,121.0

854.0

988.0

1,524.0

1,881.0

4,223.0

2,143.0

1,005.0

984.0

2,021.0

1,930.0

4,922.0

2,195.0

1,199.0

843.0

2,605.0

1,920.0

5,411.0

2,969.0

1,082.0

884.0

2,456.0

1,980.0

6,138.0

3,400.0

952.0

1,084.0

2,987.0

2,285.0

6,533.0

3,613.0

1,012.0

1,156.0

3,182.0

2,430.0

6,108.4

—

—

—

—

—

6,517.6

—

—

—

—

—

GDP by Expenditure (%)

Private Consumption

Government Consumption

Gross Fixed Investment

Exports of Goods & Services

Imports of Goods & Services

100.0

59.0

24.8

24.4

40.6

49.0

100.0

58.8

23.7

27.4

42.3

52.2

100.0

50.7

23.8

23.3

47.9

45.7

100.0

44.6

24.4

17.1

52.9

39.0

100.0

54.9

20.0

16.3

45.4

36.6

100.0

55.4

15.5

17.7

48.7

37.2

100.0

55.3

15.5

17.7

48.7

37.2

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

GDP by Industry (K mill)

Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries

Mining & Petroleum

Manufacturing, Construction & Power

Commerce, Transport & Fin. Services

Services & Import Duties

3,076.0

891.0

452.0

483.0

511.0

739.0

3,606.0

937.0

613.0

628.0

639.0

789.0

4,140.0

1,020.0

925.0

666.0

666.0

863.0

5,016.0

1,335.0

1,381.0

667.0

724.0

909.0

5,409.0

1,546.0

1,366.0

714.0

749.0

1,034.0

6,442.0

1,693.0

1,927.0

773.0

896.0

1,153.0

6,533.0

1,731.0

1,719.0

885.0

984.0

1,214.0

6,108.4

—

—

—

—

—

6,517.6

—

—

—

—

—

GDP by Industry (%)

Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries

Mining & Petroleum

Manufacturing, Construction & Power

Commerce, Transport & Fin. Services

Services & Import Duties

100.0

29.0

14.7

15.7

16.6

24.0

100.0

26.0

17.0

17.4

17.7

21.9

100.0

24.6

22.3

16.1

16.1

20.8

100.0

26.6

27.5

13.3

14.4

18.1

100.0

28.6

25.3

13.2

13.8

19.1

100.0

26.3

29.9

12.0

13.9

17.9

100.0

26.5

26.3

13.5

15.1

18.6

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

Fiscal Indicators

Government Revenues & Grants (K mill)

Government Spending (K mill)

Budget Balance (Revenue less Spending)

998.0

1,089.0

(91.0)

1,026.0

1,188.0

(162.0)

1,126.0

1,358.0

(232.0)

1,309.0

1,605.0

(296.0)

1,446.0

1,570.0

(124.0)

1,722.0

1,755.0

(33.0)

1,898.0

1,861.0

37.0

2,202.9

2,188.5

14.4

2,411.3

2,499.9

(88.6)

Money, Rates, Prices & Exchange Rates

M1 (Narrow Money, K mill)

M3 (Broad Money, K mill)

6-Month Treasury Bill Rate (%)

Consumer Price Inflation (%)

Official Exchange Rate: $US/Kina

353.3

1,334.4

10.5

7.0

1.047

458.0

1,505.9

10.5

7.0

1.050

509.1

1,647.9

6.5

4.0

1.037

527.5

1,812.5

6.0

5.0

1.022

571.3

1,860.1

10.8

3.0

0.995

645.9

2,068.0

21.5

17.0

0.784

864.9

2,736.8

14.4

11.6

0.759

—

3,068.8

10.5

3.9

0.698

—

—

18.1

11.5

0.5339

3.70

1.9

94.6

(4.7)

3.77

1.9

91.1

(3.7)

3.85

2.1

94.0

3.2

4.00

2.0

98.1

7.3

4.07

1.8

93.5

(4.7)

4.15

1.9

100.5

7.5

4.23

1.9

101.5

1.0

4.31

1.9

—

—

(88.0)

86.0

(287.0)

113.0

207.0

(111.0)

8.0

(144.0)

75.0

(466.0)

247.0

60.0

3.0

(81.0)

Population & Employment

Population (million)

Population Growth (% per year)

Employment Index (1989 = 100)

Employment Growth (%)

Balance of Payments (K mill)

Current Account Balance

Trade Balance

Services Balance

Transfers

Capital Account Balance

Errors & Omissions

Overall Balance

International Reserves Minus Gold ($US m)

Total Public Debt Outstanding (K mill)

Domestic Debt (K mill)

Foreign Debt (K mill)

Total Debt as Share of GDP (%)

94.0

607.0

(699.0)

186.0

(146.0)

(16.0)

(68.0)

3.92

1.8

91.4

(2.8)

632.0

1,437.0

(847.0)

42.0

(701.0)

(27.0)

(96.0)

576.0

1,346.0

(781.0)

11.0

(627.0)

3.0

(48.0)

859.0

1,800.0

(1,034.0)

93.0

(556.0)

(19.0)

284.0

411.0

1,338.0

(1,011.0)

41.0

58.0

(38.0)

431.0

(148.0)

965.0

—

—

2.0

—

(154.0)

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

403.0

323.1

238.6

141.5

96.1

261.4

583.9

362.7

—

1,470.0

406.0

1,064.0

47.8

1,567.0

556.0

1,011.0

43.5

1,945.0

824.0

1,121.0

46.1

2,320.0

1,037.0

1,283.0

47.1

2,935.0

1,425.0

1,510.0

54.2

3,284.0

1,606.0

1,678.0

53.5

3,763.3

1,969.3

1,794.0

57.6

—

2,251.7

—

—

—

—

—

—

Note: Most 1997-98 quantities are based on projections, forecasts and preliminary numbers subject to revision and change.

Sources: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics (yearbook), Bank of Papua New Guinea, Quarterly Economic Bulletins (various),

AusAid, Economic Survey of Papua New Guinea, August 1997; Monthly Economic Monitor, April 10, 1998, Economic Policy Unit, Treasury and Corporate

Affairs, Waigani, PNG.

16

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

national resources. Even in some developed economies,

budget deficits have amounted to relatively large

percentages of GDP, depending on the circumstances.

While PNG’s budget deficit ranged from 0.5 percent of

GDP to 6.0 percent (averaging 3.0 percent in 1990-96), a

small 0.6 percent surplus was achieved in 1996.

With the conclusion of the Bougainville conflict

which consumed public funds, especially in 1992-95 when

the government attempted to quell the rebellion with force,

PNG’s fiscal health should improve in the years ahead.

Also contributing positively to fiscal health in the future

will be royalties and taxes from new mines, including those

on Bougainville when they reopen.

Further pressure on the government to manage its

finances arises from conditions attached to structural

adjustment loans from the World Bank and IMF. As the

economy emerges from the present crisis caused by natural

disasters, global commodity price drops and devaluation,

prospects for PNG’s financial health are strengthened by its

return to stability and the steady flow of foreign aid,

especially from Australia.

(K692 million) during the two-year period was in the form

of short-term securities.

Taking advantage of increased liquidity and the

availability of other external funds such as foreign aid, the

Bank of Papua New Guinea eased monetary policy in mid1996, which helped reduce interest rates. The 182-day

T-Bill rate dropped from a record 21.5 percent in February

1996 to 9.2 percent in December 1996. In September 1997,

the rate was down to 8.8 percent. The weighted average of

loan advances dropped from 15.4 percent in January 1996

to 10.2 percent in December the same year. In September

1997, the rate was slightly higher at 10.5 percent.

At the end of the first quarter 1998, the 182-day bill

rate was back up to 18.1 percent and expected to rise

further, partially as a result of tighter monetary policy

necessitated by price inflation connected to devaluation.

With the 182-day bill rates rising, the spread between it and

the average of other commercial lending rates is widening,

making underwriting T-bills more attractive, especially for

commercial banks. This consequence of market changes

was largely unexpected, thus further complicating the

financial market’s behavior. It will be some time before a

clearer picture of PNG’s financial markets emerges,

especially in light of other developments connected to

regional economic and financial dilemmas, including

pressure on the Kina to depreciate even more.

2.4 MONETARYPOLICY

Allowing market conditions to play a larger role in

determining interest rates has been the main feature of

PNG’s monetary policy until the current recession. This

policy has been consistent with others that aim to make the

PNG economy more market-oriented and bring both fiscal

and monetary policies in line with similar movements in the

region. This is a significant movement, especially in a

developing economy where the central bank has

traditionally been less independent than in developed

economies. More market orientation is expected as PNG

puts better fiscal and economic management methods in

place and gets ready for major projects such as the natural

gas pipeline to Queensland.

The total money supply in PNG (M3) consists of the

so-called narrow money (M1) encompassing notes, coins

and demand deposits, and quasi-money (M2) which

includes savings, term deposits and other items. In 1996,

total money supply (M3) was K2.7 billion of which 31.6

percent was M1, 45.9 percent was term deposits and 11.4

percent was saving deposits.

M3 increased 11.2 percent in 1995 and 32.3 percent

in 1996. Large balance of payment surpluses contributed to

the enormous gains in money supply. Another contributing

factor was increased funding of government debt by

commercial banks, which rose from K756 million in 1995

to K1.132 billion in 1996. More than half of this total

2.5 PNG’S EXTERNALACCOUNTS

The importance of external trade to PNG can be seen

in its external transactions as shares of GDP. Exports of

goods and services averaged 46.6 percent of GDPin 1990-96,

ranging from a low of 40.6 percent in 1990 to a high of 52.9

percent in 1993. (In the United States, exports of goods and

services amounted to 11.9 percent of the GDP in 1997.)

Imports of goods and services have likewise been critical to

PNG’s economic health. They averaged 42.4 percent of

GDP, ranging from a high of 52.2 percent in 1991 to a low

of 36.6 percent in 1994. (The comparable number for the

United States in 1997 was 13.1 percent.)

Australia remains PNG’s largest trading partner,

accounting for half of its imports and a third of its exports.

Japan is the second largest trading partner for PNG,

supplying about 20 percent of its imports and a slightly

higher share of exports. Imports from the United States

account for about 10 percent, while exports to Korea

represent 10 percent also. The rest of Asia and the

European Union are relatively minor participants in PNG’s

international trade.

PNG’s wide variety of exports, although mostly

17

PA P U AN E W GUINEA (PNG) ECONOMIC REPORT • SEPTEMBER 1998

commodities, has enabled it to have current account

surpluses during most of this decade, mainly as a result of

trade surpluses which have compensated for service and

capital account deficits. The capital account has fluctuated

between small surpluses and relatively large deficits.

Surpluses occurred when foreign interests made large

investments or loans in the mineral sector, and deficits

occurred when some of the loans related to minerals were

repaid. This will most likely be the pattern in the years ahead

as PNG begins to utilize more of its mineral resources.

PNG’s external accounts exhibit a more positive

picture than one would expect from a developing economy

in the early stages of change. Credit is attributed to its

exports in minerals (gold, copper and oil), logs, palm oil,

coffee and other commodities as well as capital inflows. In

addition, foreign aid contributes significantly to the overall

external sector.

focused on making the economy more market-oriented and

efficient. Unforeseen and uncontrollable commodity price

changes will continue to generate uncertainty in PNG, for

both foreign investors and the government of PNG. Efforts

may be needed in the future to minimize fluctuations, though

no effort will completely eliminate commodity price changes.

III. ECONOMY BY SECTOR

PNG is a developing economy in the true sense, thus

accurate and current data are scarce. The government is

making a serious effort to implement accurate and timely

information-gathering and dissemination methods. In the

meantime, overseas observers must rely on a mix of

anecdotal evidence, field visits to the country and

information sources among government, business and

traditional leaders in order to assess realistically PNG’s vast

resources, its productive potential, income and prospects for

growth. PNG’s tourism slogan, “PNG, the Unexpected,”

reflects both its present structure and future promise.

2.6 PNG’S DEBTAND PAYMENTS

Total public debt has risen recently, reflecting

government’s larger burden, especially in borrowing to