The Bundesrat and the federal state system

Internet

The Bundesrat http://www.bundesrat.de

Information about the federal states http://www.bundesrat.de

Bills and ordinances adopted by the Federation http://www.bundesrecht.juris.de/bundesrecht/GESAMT_a.html

Subject-specific sites/Federalism

The European Centre for Federalism Research in Tübingen is planning to develop an online documentation resource on federalism. The Centre’s homepage offers a broad range of links offering more information.

http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/ezff

International servers

Committee of the Regions http://www.cor.europa.eu

European Union http://www.europa.eu

Austrian Legal Information System http://www.ris.bka.gv.at

Swiss server for legal experts http://www.legalresearch.ch

This brochure invites you to find out about the Bundesrat. It is a striking splash of colour in the ranks of legislative bodies. The Bundesrat’s composition and the range of roles it fulfils are entirely unique.

Germany’s federal system is the framework within which the

Bundesrat’s particular meaning and significance emerge.

The brochure opens with an introduction to the key traits of German federalism, in which the “parliament of the federal states’ governments” forms a link between the central federal level and the individual federal states. This is followed by an explanation of the

Bundesrat’s composition, organisation and working methods. A brief historical overview offers insights into the constitutional tradition in which the Bundesrat is embedded.

An index assists readers looking for specific terms. A bibliography and some Internet links are provided for readers who would like to do more reading on the subject.

Bundesrat

Public Relations

11055 Berlin

Germany www.bundesrat.de

We would be delighted to send you further copies of this brochure or other information material about the Bundesrat or federalism free of charge.

The Bundesrat and the federal state system

The Federal Council of the Federal Republic of Germany

The federal state system

A federal constitutional body

Federalism – unity in diversity

Distinct roles and shared responsibilities

Organisation and working methods

The seat of the Bundesrat

The Plenary session

Distribution of votes

The members

The President and the Presidium

Voting

Plenary sessions

The Chamber of European Affairs

The committees

The Mediation Committee

The Bundesrat’s working methods

The roles played by the Bundesrat

The Bundesrat – a federal body

The roles played by the Bundesrat

1. Submitting opinions on draft government bills

2. Convening the Mediation Committee

3. Taking decisions on consent bills

4. Participating in addressing objection bills

5. Bundesrat draft bills

6. Statutory instruments

7. Consent to general administrative regulations

8. European Union draft legislation

9. Participation in foreign affairs

10. Right to be informed by the Federal Government

11. Other roles

The status of the Bundesrat

A second chamber?

The mandate

Taking decisions as a federal constitutional body

Taking decisions as a political constitutional body

Counterweight involved in monitoring the Federal Government

Counterweight involved in rectifying Bundestag decisions

Link between the Federation and the federal states

Building on a sound tradition – forerunners of the Bundesrat

Overview of legislative activities

Annex

Bibliography

Index

Internet

4

5

10

56

59

61

62

64

50

52

53

54

18

20

23

24

14

14

16

17

25

27

29

36

41

41

42

34

34

35

36

43

44

45

46

47

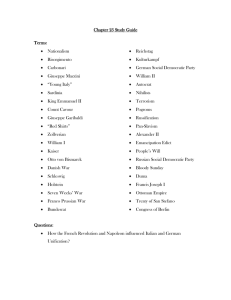

Coats of arms of the Federation and the 16 federal states

Baden-

Württemberg

Area: 35752 km 2

Berlin

Area: 891 km 2

Bremen

Area: 404 km 2

Hesse

Area: 21115 km 2

Lower Saxony

Area: 47641 km 2

Rhineland-

Palatinate

Area: 19853 km 2

Saxony

Area: 18417 km 2

Schleswig-Holstein

Area: 15799 km 2

Bavaria

Area: 70552 km 2

Brandenburg

Area: 29480 km 2

Hamburg

Area: 755 km 2

Mecklenburg-Western

Pomerania

Area: 23182 km 2

North Rhine-

Westphalia

Area: 34086 km 2

Saarland

Area: 2569 km 2

Saxony-Anhalt

Area: 20447 km 2

Thuringia

Area: 16172 km 2

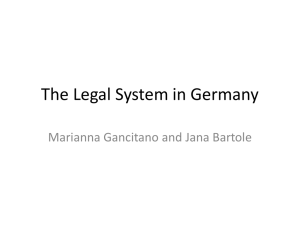

Distribution of votes in the Bundesrat

Total of 69 votes

Schleswig-Holstein

2,8 million Kiel

Hamburg

1,8 million

Hamburg

Schwerin

Lower Saxony

8,0 million

Bremen

Bremen

0,7 million

North-Rhine Westphalia

18,0 million

Hannover

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

1,7 million

Berlin

Magdeburg Potsdam

Saxony-Anhalt

2,4 million

Brandenburg

2,5 million

Berlin

3,4 million

Düsseldorf

Bonn

Hesse

6,1 million

Rhineland-Palatinate

4,0 million

Wiesbaden

Mainz

Saarland

1,0 million

Saarbrücken

Erfurt

Thuringia

2,3 million

Dresden

Saxony

4,2 million

Bavaria

12,5 million

Stuttgart

Baden-Württemberg

10,7 million

Munich

Each federal state has at least three votes

States with more than 2 million inhabitants have four votes

States with more than 6 million inhabitants have five votes

States with more than 7 million inhabitants have six votes

Total population 82.1 million

Source: Federal Statistical Office, 2008

Bibliography

1. Works of collected articles on the Bundesrat

Handbuch des Bundesrates / Bundesrat (Ed.),

New edition annually

Der Bundesrat im ehemaligen Preußischen

Herrenhaus / Bundesrat (Ed.), 2002

Der Bundesrat / Ziller, Gebhard/Oschatz, Georg-Berndt,

10th edition 1998

Der Bundesrat. Mitwirkung der Länder im Bund /

Pfitzer, Albert, 4th edition 1995

Praxishandbuch Bundesrat: verfassungsrechtliche

Grundlagen, Kommentar zur Geschäftsordnung,

Praxis des Bundesrates / Reuter, Konrad, 1991

Miterlebt – Mitgestaltet. Der Bundesrat im Rückblick /

Hrbeck, Rudolf (Ed.), 1989

Das Parlament der Regierenden. 40 Jahre Bundesrat.

Eine Chronik seiner Präsidenten / Herles, Helmut, 1989

2. Essays on the Bundesrat

Bundestag und Bundesrat bei der Umsetzung von

EU-Recht / Zeh, Wolfgang / In: Der Politikzyklus zwischen

Bonn und Brüssel / Derlien, Hans-Ulrich et al (Ed.), 1999, pp. 39 – 51

Das parlamentarische Regierungssystem und der

Bundesrat – Entwicklungsstand und Reformbedarf /

Dolzer, Rudolf/Sachs, Michael / In: Veröffentlichungen der

Vereinigung der Deutschen Staatsrechtslehrer, Vol. 58,

1999, pp. 7–77

Die Rolle des Bundesrates und der Länder im Prozeß der deutschen Einheit / Klein, Eckart (Ed.), Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Deutschlandforschung, Vol. 66,

1998

Zusammensetzung und Verfahren des Bundesrates /

Herzog, Roman / In: Handbuch des Staatsrechts der

Bundesrepublik Deutschland / Isensee/Kirchhof (Ed.),

Vol. 2, 2nd edition 1998, pp. 505– 522

3. Works of collected articles on federalism

Die deutschen Länder: Geschichte, Politik, Wirtschaft /

Hans-Georg Wehling (Ed.), 2nd edition 2002

Ende des Föderalismus: Gleichschaltung und

Entstaatlichung der deutschen Länder von der nationalsozialistischen Machtergreifung bis zur Auflösung des Reichrats / Talmon, Stefan, in: Zeitschrift für neuere

Rechtsgeschichte, 24 (2002), pp. 112–155

Föderalismus: Analysen in entwicklungsgeschichtlicher und vergleichender Perspektive / Benz, Arthur (Ed.),

Deutsche Vereinigung für Politische Wissenschaft,

Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Sonderheft, 32/2001

German federalism: past, present, future / ed. by

Maiken Umbach. – 1. publ. Basingstoke [et al.]. Palgrave,

2002

Föderalismus in Deutschland / Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Ed.), Informationen zur politischen Bildung,

No. 275, 2002

Föderalismus: eine Einführung / Sturm, Roland/

Zimmermann-Steinhart, Petra, 2005

Das föderative System der Bundesrepublik

Deutschland / Laufer, Heinz/Münch, Ursula, 7th edition

1997

Föderalismus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: eine Einführung / Kilper, Heiderose, 1996

Föderalismus: Grundlagen und Wirkungen in der

Bundesrepublik Deutschland / Reuter, Konrad,

5th edition 1996

Zustand und Perspektiven des deutschen

Bundesstaates / Blanke, Hermann-Josef/Schwanengel,

Wito (Ed.), 2005

Föderalismusreform in Deutschland / Hennecke, Hans-

Günter (Ed.), 2005

Dokumentation der Kommission von Bundestag und

Bundesrat zur Modernisierung der bundesstaatlichen

Ordnung / Deutscher Bundestag, Bundesrat, Öffentlichkeitsarbeit (Ed.), 2005

Europäischer Föderalismus im 21. Jahrhundert /

Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismusforschung (Ed.),

2003

Der deutsche Bundesstaat in der EU: die Mitwirkung der deutschen Länder in EU-Angelegenheiten als

Gegenstand der Föderalismus-Reform / Hrbek, Rudolf, in: Europa und seine Verfassung/Gaitanides, Charlotte

(u.a.) (Ed.), 2005, pp. 256–273

Föderalismus und Integrationsgewalt: die

Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Spanien, Italien und

Belgien als dezentralisierte Staaten in der EG /

Blanke, Hermann-Josef, 1991

Index of topics

Abstention

Agenda

22

23, 26, 31

Bill passed by the Bundestag 28, 38f., 64

Bound by instructions 21, 27, 50

Budget

Bundesrat (Kaiserreich)

20

62

Bundestag 4, 18, 36, 44f., 47, 59ff.

Call to order

Casting of votes

Casting votes en bloc

Centralised state

Chamber of European

23

17, 20ff.

20f.

5ff.

Union Affairs

Chamber of the

24ff., 44 federal states 34, 50, 54f., 61

Checks and balances, system of controls

Coalition government

Coat of arms

Committees

6ff., 56ff.

20

23

18f., 25ff., 30, 46

– Committee members

– Committee meetings

Consent bill

25ff.

18, 27, 56, 64

28, 36ff., 59, 64

Distribution of votes

Division of powers

Draft bill

16

4ff., 10f., 59f.

35f

– Draft bill introduced by the Bundesrat

38f., 64

– Draft bill introduced by the Bundestag 36f.

– Draft bill introduced by

– the federal government 30, 35f., 64

European Union 11, 30, 53

Federal Constitutional Court 4, 19, 37f., 48ff.

Federal Government

4, 26, 35f., 42ff., 56ff., 61

Federal President

Federal state

Federalism

Foreign policy

Incompatibility

Interests of the federal states

4, 19, 37, 48

3ff., 40, 52f., 59

4ff., 34, 52

44ff., 57

18

32ff., 52ff., 58ff.

Länder governments 14ff.

Länder parliaments

Landesvertretung, representative office of federal state

Legal ordinance

7

20, 31

42f., 57, 64

Legislative emergency

Legislative procedure

47, 54

34ff., 51

Mediation Committee 27ff., 36ff., 43, 64

Meeting/session

– Bundesrat plenary session 23f., 29f., 64

– Meeting of the Chamber

– of European Affairs 24f., 44, 64

– Meeting of Bundesrat Committees

25ff., 30f., 64

– Meeting of Mediation Committee 27ff., 36

Member

– Members of the Bundesrat 14ff., 27

– Member of Bundesrat committee 25ff.

– Member of the Chamber of

– European Affairs 25

– Member of the Mediation Committee 27f.

Minutes of the meeting

Objection bill

Official document

Opposition

Parliamentary Council

Parliamentary group

Party politics

Permanent Advisory Council

Plenary

20, 31

13ff., 18ff., 23, 30

Plenary session 14f.

President of the Bundesrat 18ff., 22, 25, 46

Presidium

Prior discussion

18ff., 22

31

Question time

Regionalisation

Reichsrat 62

46

9

46

Seat of the Bundesrat

Second chamber

Second reading

Secretariat of the Bundesrat

14

51f.

30, 36, 46

19, 31

Secretary-General of the Bundesrat

19, 23, 29

Speaking right

– Speaking right: Member of the Bundesrat

18, 23

– Speaking right: Member of

– the federal government

State of defence

26 ,46

47, 54

Statistics

Stenographers

Subsistence allowance

64

23

18

Vice-President 18

Vote-caster

21, 23, 31

38ff.

30f.

14, 56

6, 55

27

54ff.

21, 45

The Bundesrat and the federal system

The Federal Council of the Federal

Republic of Germany

Author: Dr. Konrad Reuter

Editor: Secretary General of the Bundesrat

Berlin 2009 – 14th edition

16 federal states or Länder make up the Federal Republic of Germany. The federal system means that many political decisions are taken in the federal states. This principle is enshrined in the Basic

Law. However, the Bundestag and the Federal Government cannot determine everything on their own even when it comes to national matters at the federal level. Through the Bundesrat the federal states also have a say in Berlin.

The federal state system

A federal constitutional body

Federalism – unity in diversity

Distinct roles and shared responsibilities

The federal state system

A federal constitutional body

The Bundesrat is one of the five permanent constitutional bodies of the Federal Republic of Germany. Alongside the other components of the federal system – the Federal President, the Bundestag (Federal Parliament), the Federal Government and the Federal Constitutional Court – the Bundesrat is the body within the federal structure that represents the interests of the federal states. The Bundesrat participates in the Federation’s policy decisions and thus acts as a counterweight to the political bodies representing the federal tier, namely the Bundestag and the Federal Government, as well as constituting a link between the Federation and the federal states. Its status and function are described in Article 50 of the Basic Law, which since 1992 has also included an explicit reference to the European dimension of policy:

Article 50 BL “The Länder shall participate through the Bundesrat in the legislation and administration of the Federation and in matters concerning the European Union.”

The significance of this constitutional provision is most clearly revealed if one first considers the backdrop to it: the way in which the state is structured, comprising the Federation (central authority) and the federal states (Länder) – in other words, the specific form federalism assumes in Germany. Federalism has long been the form of state organisation adopted in Germany, creating state unity whilst at the same time setting limits on this within the federal system, and thus ensuring that the notion of unity is not given excessive weight.

Federal President

The five permanent constitutional bodies of the Federation

Federal government

Bundestag

Bundesrat

Federal Constitutional Court

Article 20 (2) BL “All state authority is derived from the people. It shall be exercised by the people through elections and other votes and through specific legislative, executive and judicial bodies.”

4

The federal state system

Federalism – unity in diversity

The term “federalism” is derived from the Latin word “foedus”, which can be translated as “alliance” or “treaty”. Federalism means forming a federal state and cooperating within the entity thus formed: several states enter into an alliance to form one single all-encompassing state structure (federation, confederation), whilst to a certain extent maintaining their own characteristics as states (federal states, constituent states).

This contrasts with other forms of state organisation, such as on the one hand the centralised state (unitarism), which does not have autonomous sub-units, and on the other hand the confederation. The latter is a union of states under international law, in which the individual states remain entirely independent and their union does not per se constitute a state. The German Confederation, which existed from 1815 to 1866, was an alliance of this type. In a federal state, the state as a whole should be responsible for those matters that absolutely must be regulated in a uniform manner in the interests of the people. The federal tier of government should however restrict its actions to this specific role, for all other matters should be regulated by the constituent member states. As a consequence, while many aspects in a federal system are harmonised, a range of other areas are not covered by uniform provisions. Unity in diversity is the fundamental principle underlying any genuine federal state.

It is even stated in the constitution that this fundamental principle is inviolable and unalterable. Article 79 (3), Basic Law provides:

“Amendments to this Basic Law affecting the division of the Federation into Länder, their participation on principle in the legislative process, or the principles laid down in Articles 1 and 20 shall be inadmissible.”

Article 79 (3) BL

5

The federal state system

As long as the Basic Law remains in force, there is thus an obligation to preserve the underlying fabric of the federal structure. However, that does not mean that there is no need to ponder the meaning and purpose of federalism. On the contrary, federalism would be in rather poor shape if it were merely perceived as an unalterable system.

Modern form of state

In 1949 the Parliamentary Council opted for the federative principle of state organisation, because it also implied a further division of political power between the federation and the federal states (vertical division of power), in addition to the classical division of power between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary (horizontal division of power). This twofold division of powers serves as an effective means to prevent abuse of power by any part of the system.

That is why right from the outset one of the goals of the peaceful revolution in the former GDR in 1989 was the reintroduction of the federal states or Länder in former East Germany, However, no form of statehood is perfect – except perhaps theoretically. For that reason, the pros and cons must always be weighed up against each other.

In a democracy, the litmus test is the response to a straightforward question: how does this benefit the people? The focus should be on the citizens – not on a rapid, powerful state apparatus.

Federation

Legislature

(legislation)

Executive

(government and administration)

Judiciary

(administration of justice)

Länder input and participation in decision-making by the

Federation and influence of central government on the Länder

Twofold division of powers within the federal state system

16 federal states

6

Advantages of the federal state system compared with the unitary state

+ Power-sharing

In a federation, the classical horizontal division of powers (legislative – executive – judicial) is complemented by a vertical division of powers between the state as a whole and the individual constituent states. Power-sharing means control of how power is used and protection against abuse of this power.

+ More democracy

The sub-division into smaller political units makes it easier to grasp and comprehend the actions taken by the state, thus fostering active participation and co-determination. In addition, voters can exercise the fundamental democratic right to vote and thus to participate in decisions on two fronts, for in a federal state there are elections both to the central parliament and to the parliaments of the constituent states.

+ Leadership opportunities

Political parties enjoy greater opportunities and competition between them is promoted, as minority parties at national level can nonetheless take on political responsibility in the individual states making up the federation. This offers them a chance to test and demonstrate their leadership skills and overall performance.

+ Closer to the issues

In a federation public bodies are closer to regional problems than in a unitary state. There are no far-flung “forgotten” provinces.

+ Closer to people

The federal state brings state structures much closer to the general public. Politicians and public authorities are much more accessible than in a unitary state that concentrates power in an anonymous, distant centre.

+ Competition

The constituent states always automatically compete with each other. Competition has a stimulating effect. Exchanges of experience foster progress and serve as a safeguard, ensuring that any mistakes are not repeated across the whole country.

7

The federal state system

The federal state system

+ Sound balance

Mutual checks and balances, coupled with respect for each other and a need to reach compromises make it more difficult, if not well-nigh impossible, to adopt extreme stances. As federalism strikes a fair balance, it also has a stabilising effect.

+ Diversity

The division of the country into federal states or Länder ensures that a whole host of economic, political and cultural centres can exist. That offers greater scope to preserve and develop regional customs, as well as the specific historical, economic and cultural characteristics of an area. This diversity can give rise to greater freedom.

Ultimately these arguments in favour of federalism prove to be advantages for each individual citizen. Whilst the federal system may certainly have disadvantages too, these benefits clearly outweigh the drawbacks.

Disadvantages of the federal state system compared with the unitary state

– Lack of uniformity

The federal states’ autonomy automatically leads to differences.

Diversity is the opposite of uniformity. This can cause difficulties, for example, for school children if their family moves to another federal state.

– Complicated

As there are many decision-making centres in the Federal Republic of Germany, the division of powers between the Federation and the federal states means the various tiers of state must work together, show consideration, exercise mutual oversight and also respect the limits of each part of the federal structure. The ensuing intermeshing of state activities is thus complex and can be hard for the general public to understand.

– Time-consuming

Parliaments, governments and the public administrations of the

Federation and the Länder have to wait for input, decisions or con-

8

The federal state system sent from other tiers of state, as well as engaging in lengthy negotiations with each other to reach a consensus. This can also be highly time-consuming.

– Expensive

Generally speaking, the cost of maintaining distinct parliaments, governments and public administrations at the Federation and federal state level is considered to be more expensive than running the corresponding institutions in a unitary state. It is debatable whether this assumption is correct, for it would be impossible to simply dispense with institutions in the federal states by adopting a unitary state system. Various federal bodies would certainly have to grow accordingly and it is not clear that centralised mammoth authorities would really be cheaper in the final analysis.

Federalism is not a relic from the days of the stagecoach but instead, given its adaptability, a form of statehood very much in tune with our times. Nor is it a peculiarity of the German system. Looking at maps of the world, we find a whole host of countries with a federal structure, all of which are very different from each other in the details of how the system works and the impact this has on citizens in those countries. For example, the countries in the following list are all federal states, as stipulated in their constitutions: Canada, the USA,

Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, India, Russia, Austria, Belgium and Switzerland. Even such traditionally centralistic states as France,

Spain and Italy have shifted to “regionalising” their countries, which, although it does not constitute federalism, is nonetheless a step in that direction. And one thing is certain: a united Europe will only be able to survive as a federative union of states, not as something akin to a centralised state. Federalism is therefore a form of state with a future, particularly in Europe.

A form of state with a future

“Just as the Länder have made a decisive contribution to integrating the plurality of cultural and social traditions into the nation-state, the regions within a united Europe will be essential participants in allowing diversity to merge into political unity.”

Kurt Beck,

President of the Bundesrat

(2000/2001)

9

The federal state system

Distinct roles and shared responsibilities

Division and intermeshing

The Basic Law ascribes particular roles to the Federation and the federal states in the spheres governed by the legislature, executive and judiciary. Generally speaking, it is fair to say that the Federation is responsible for legislation in most spheres, administration is in essence handled by the federal states and responsibilities in the judicial sphere are closely intermeshed, involving both the Federation and the federal states. Nonetheless, the federal states also have significant legislative responsibilities, particularly for policies on culture and education, local government law and the police forces. Similarly the Federation also has a fully-fledged administrative substructure in certain areas, for example for the foreign services, the armed forces and employment offices. Generally however the following principle applies:

Legislation is on the whole dealt with by the Federation.

Public administration is on the whole a matter for the federal states.

This division of responsibilities gives the Federation a powerful position, as it can establish uniform standards for all federal states and the population at large through its overarching legislative competence.

However, the federal states – and this is an important compensatory mechanism – may participate in the Federation’s legislative process via the Bundesrat: federal laws that particularly affect the concerns of the federal states may only be adopted with the explicit consent of the Bundesrat. As a consequence, on the one hand the

Länder are subject to “the will of the Federation”, which limits their political autonomy; on the other hand, however, they can have an

10

The federal state system influence on the Federation’s deliberations and thus contribute to the emergence of this “federal will”. The Federation and the federal states are closely interlinked.

The Bundesrat constitutes a link binding the Federation and the federal states. Its role is to ensure that irreconcilable contradictions do not arise between the central state and the individual federal states although responsibilities are divided between the various tiers of state.

The Bundesrat forms a bond

The Bundesrat’s role as mediator determines its constitutional status and its composition:

The Bundesrat is a constitutional body of the federation, but it is made up of representatives of the federal states. This in a sense compensates the federal states for the fact that they have to a large extent relinquished their independent legislative competence, and also grants them the right to have a say when the Federation devises administrative provisions. Through the Bundesrat the federal states also have an opportunity to participate in matters pertaining to the European Union.

The Bundesrat is a body of the (federal) legislative, but it is made up of members of the (federal states’) executive bodies. This structure means that federal legislation can draw directly on the administrative experience of the federal states.

The Bundesrat has been described as probably “the most original

German contribution to federalism”. The structure, organisation and remit of the Bundesrat is quite unique among second chambers and can ultimately only be understood properly if one considers the long constitutional tradition embodied by the Bundesrat.

“The Basic Law takes the idea of federalism based on solidarity. Germans from former East Germany made a conscious decision to opt for this inner unity after the fall of the

Wall. We should understand the call for more competition as a complement to the solidarity principle rather than as a substitute for it.”

11

Matthias Platzeck,

President of the Bundesrat

(2004/2005)

Who is represented in the Bundesrat, who is authorised to take part in deliberations there, who may vote? How do the decision-making processes work?

This chapter presents the membership and structure of the various bodies in the Bundesrat. The focus is on presenting how the Bundesrat’s day-to-day work is done, a topic rarely addressed directly in the media. The atmosphere, style and working methods are significantly different from those in the Bundestag: work in the Bundesrat has a different rhythm and functions according to a distinct procedure.

Organisation and working methods

The seat of the Bundesrat

The plenary session

Distribution of votes

The members

The President and the Presidium

Voting

Plenary sessions

The Chamber of European Affairs

The committees

The Mediation Committee

The Bundesrat’s working methods

Organisation and working methods

The seat of the Bundesrat

The move from

Bonn to Berlin

On 1st August 2000 the building at Leipziger Straße 3–4 formerly occupied by the Herrenhaus (House of Lords), the upper chamber of the Prussian parliament, became the Bundesrat’s seat in Berlin. There is also a branch office in the “federal city of Bonn”. Some committees meet there regularly several times a year.

Before August 2000 the Bundesrat’s official seat had been in the Bundeshaus in Bonn, along with the Bundestag, ever since the Bundesrat’s first constitutive meeting on 7th September 1949. Before the

Bundesrat moved into the plenary hall in Bonn, which still exists today, the venue was used for meetings of the Parliamentary Council, which drew up the Basic Law there in 1948/49. Next to it stood the plenary hall of the Bundestag, which was constructed from scratch in 1949.

The plenary session

The essence of the Bundesrat is the assembly of all its members, the plenary session. Its composition is stipulated in Article 51 of the Basic

Law:

Article 51 (1) BL “The Bundesrat shall consist of members of Land governments, which appoint and recall them.”

That means that in order to be a member of the Bundesrat, one must have a seat and a say in a government at federal state level. The government in each of the federal states decides which of its members will be appointed to the Bundesrat. However, the number of full members each federal state may appoint to the Bundesrat is determined by the number of votes that state holds in the Bundesrat. The remaining members of the cabinets in the federal states are however generally appointed as alternate members of the Bundesrat, which means that in practice all the members of a Land government belong to the Bundesrat. All of the c. 170 appointed members de facto enjoy exactly the same rights, as the Bundesrat’s rules of procedure grant the same rights to alternate and full members. The Bundesrat is a parliament of the federal states’ governments. There is no scope for the opposition in the various federal states to make its voice heard directly in the Bundesrat.

14

Organisation and working methods

There is no such thing as “elections to the Bundesrat”, and thus the Bundesrat does not have legislative terms as such. In constitutional parlance it is a permanent body, whose membership is renewed from time to time as a consequence of elections at federal state level. As a result, elections to the parliaments in the federal states always have nationwide political significance too. As early as the 1950s the slogan was: “Your vote in the Hesse state decides who's on the Bundesrat's slate”. Whilst voters first and foremost determine the composition of the parliament in their federal state and thus which party or parties will govern their federal state, at the same time this indirectly determines who will have a seat and a say in the Bundesrat, for the majority in each Land parliament makes up the government of that federal state, which in turn appoints members from its ranks to the Bundesrat. This procedure is also the foundation stone for the Bundesrat’s democratic legitimacy, as its composition is determined by elections expressing the will of the people. The political power exercised by the Bundesrat stems from the electorate.

A permanent body

Bundesrat

Land government

Landtag

(federal state parliament)

15

Electorate

(in each federal state)

Organisation and working methods

Distribution of votes

States and population figures

Must all of the constituent states have the same number of representatives in the federative body representing them at national level

– for example, with each individual state having two senators, as is the case in the US Senate? Or would it be fairer and more democratic to take population figures as the yardstick, which would mean that North Rhine-Westphalia, for example, would have 26 times more votes than Bremen? An integral part of the “constitutional

DNA” in Germany is the principle of a weighting system for the number of votes allocated to represent each of the constituent states. Whilst the system is shaped by population figures in each federal state, this is not the only decisive element. Each of the federal states united in the overall state structure also “counts” in its own right. The result is a system that is a hybrid of federative and democratic representation. However, the Basic Law definitely wished to avoid a structure that would allow the larger federal states to overrule the others, whilst at the same time not making it possible for the smaller federal states to have more power than their size would merit. When the Basic Law was adopted in 1949 each of the federal states was therefore allocated at least three votes, those with over two million inhabitants were granted four votes, while five votes were given to the federal states with a population of more than six million.

New rules in the united Germany

The introduction of the five relatively small federal states from the former GDR into this system cast a new light on the balance struck between the votes allocated to small, medium and large states. It was felt that the four largest federal states should still be able to function as a blocking minority (one-third of all votes) in respect of amendments to the constitution. Article 51 (2) of the

Basic Law was therefore amended in the Treaty of Unification of

31st August 1990. A fourth category of voting rights was established, allocating six votes to federal states with a population of more than seven million.

Article 51 (2) GG “Each Land shall have at least three votes; Länder with more than two million inhabitants shall have four, Länder with more than six million inhabitants five, and Länder with more than seven million inhabitants six votes.”

16

Organisation and working methods

The number of votes in each of the federal states is indicated on the front flap. The Bundesrat has a total of 69 votes and thus 69 full members. Accordingly, 35 votes are needed for an absolute majority, which is generally necessary to adopt a decision, whilst 46 votes are required for the two-thirds majority stipulated in certain instances.

The members

Only the Minister-Presidents and Ministers in the federal states, (or

Mayors and Senate members in the case of the city-states of Berlin,

Bremen and Hamburg) may be members of the Bundesrat. State

Secretaries who have a seat and a say in the cabinet of a federal state are also entitled to be members of the Bundesrat. Membership is based on a decision adopted by each federal state government; it ends automatically if a member either leaves the Land government or is recalled due to a decision taken by the Land government.

Only cabinet members from the federal states

This means that all members of the Bundesrat have a twofold role to play. They hold a position both at federal state and national level; they are politicians in both the Land and at federal level. Members of the Bundesrat take on comprehensive political responsibility as a result. They cannot simply ignore how decisions they take within their particular federal state will impinge on national policy, whilst in their ministries in the federal states they experience first-hand the consequences of policies they pursue at the national level.

Dual function

Individual members are not free to simply vote as they see fit, for each federal state must vote en bloc in the Bundesrat. Being a member of the Bundesrat does not therefore give members a “free mandate” but nor does it imply an “imperative mandate”. Members of the

Bundesrat vote in accordance with a uniform line devised jointly by the cabinet members in each individual federal state. They represent their federal state.

The mandate – each federal state votes en bloc

17

Organisation and working methods

If no decision can be reached on how votes are to be cast and the representatives of a particular Land therefore do not all cast the same vote in the Bundesrat, that federal state’s vote is not valid. Due to the absolute majority required to adopt decisions in the Bundesrat, the final outcome of this kind of non-uniform voting is tantamount to the federal state casting a “no” vote or abstaining. Any member of the Bundesrat present in the meeting can therefore undermine a vote in favour of a motion.

Members of the Bundesrat are not remunerated for their work in the

Bundesrat. They merely receive a subsistence allowance, along with a per-kilometre allowance for road and air travel; members of the

Bundesrat are entitled to free tickets for rail travel.

Speaking rights in the Bundestag

Members of the Bundesrat enjoy an important right, which one might even describe as a prerogative, pursuant to Article 43 of the Basic

Law: they may attend all sessions of the Bundestag and its committee meetings and have the right to be heard there at all times. Furthermore, they may also appoint “representative” to exercise this right on their behalf. Members of the Bundestag do not enjoy similar opportunities to provide information and present their position in the

Bundesrat.

Dual membership of the Bundesrat and Bundestag is prohibited. The two offices cannot be combined (incompatibility).

The President and the Presidium

Annual rotation among the

Minister-Presidents

All the federal states have equal rights when it comes to the most senior position representing the Bundesrat: every year one Minister-

President is elected to this position. The order is determined as a function of the population figures of the various federal states and the cycle begins with the head of government in the most populous federal state. The Minister-Presidents agreed upon this system in

1950 in Königstein/Taunus. One of the merits of this “Königstein

Agreement” is that each of the federal states assumes the presidency once every sixteen years, although the main advantage is certainly that appointments to this position are not subject to shifting majorities and party political considerations.

18

Organisation and working methods

The President’s main duty is to convene and chair the Bundesrat’s plenary sessions. In legal terms he or she represents the Federal

Republic of Germany in all Bundesrat matters. The Bundesrat

President is assisted by two Vice-Presidents, who advise the

President in the conduct of official duties and deputise if the President is absent.

The Bundesrat President is the highest administrative authority for the Bundesrat’s officials. The Bundesrat Secretariat, with c. 185 staff members, is primarily in charge of providing practical back-up for the preparation and conduct of plenary and committee meetings. It acts under the aegis of the Secretary General of the Bundesrat and is divided up into: Committee Offices; the Office of the President,

Parliamentary Relations; Parliamentary Service; Press and Public

Relations, Visitor Service, Petitions and Submissions; Information

Technology; Documentation; Administration; Stenographic Service.

In addition, the Basic Law ascribes a further particularly responsible role to the President of the Bundesrat outside the sphere of the Bundesrat:

Powers of the head of state

“If the Federal President is unable to perform his/her duties, or if his/her office falls prematurely vacant, the President of the Bundesrat shall exercise his/her powers.”

Article 57 BL

This representative role is crucial, particularly if the Federal President is on an official visit abroad or is taking leave. In such cases, the Bundesrat President is responsible, for example, for signing bills, formally receiving diplomatic credentials from foreign ambassadors, as well as for appointing and dismissing civil servants.

In protocol terms the Bundesrat President is often considered to rank as “No. 2” after the Federal President because of this representational role. However, there is no binding definition of protocol rank-

19

Organisation and working methods ings in the Federal Republic of Germany. For that reason there is no definitive answer to the question of which of the supreme representatives of the constitutional bodies (Bundesrat, German Bundestag,

Federal Government and Federal Constitutional Court) ranks second after the Federal President, who is undisputedly the highest ranking representative of the state in protocol terms.

The Bundesrat’s budget

The Presidium of the Bundesrat, i.e. the President and the two Vice-

Presidents, are responsible for drawing up the Bundesrat’s draft budget plan, which always keeps a very tight rein on expenditure. At around 19 million Euro, the “Separate budgetary plan 03 – Bundesrat” is one of the smallest budget items within the Federation’s total budget, which amounted to around 261.7 billion Euro for 2006

(in other words c. 261.700 million Euro). That means per annum the

Bundesrat’s budget amounts to about 23 cents per inhabitant of the

Federal Republic.

Permanent

Advisory Council

The Presidium is assisted by a Permanent Advisory Council, which is composed of the sixteen plenipotentiaries of the federal states to the

Federation. Like the Council of Elders in other parliaments, this body advises the President and Presidium. However, it also plays a key role in the realm of information and coordination. After cabinet meetings on Wednesdays, a member of the Federal Government regularly provides information to the Permanent Advisory Council about the deliberations and decisions of the Federal Government.

Offices of the federal states

Each of the German federal states has a representative office in

Berlin to ensure that federal state interests are taking into account by the Bundesrat, Bundestag, Federal Government and other bodies based in the capital. Each of these offices is headed by the respective “plenipotentiary of the federal state to the Federation”. These plenipotentiaries are generally also members of the Bundesrat if they are members of the government in their federal state.

Voting

Each federal state casts its votes en bloc

As stipulated in the Basic Law, each federal state must cast its votes en bloc, voting either for or against a motion or abstaining. Each individual state government must therefore reach an agreement as to how votes should be cast before voting takes place in the Bundesrat.

20

Organisation and working methods

The way votes are cast in the Bundesrat can lead to severe tensions, particularly in coalition governments, which can strain cohesion in a coalition to breaking point.

The position of each federal state should be reflected in the Bundesrat, not that of individual members of the Bundesrat. The rules on casting votes en bloc are also there to ensure that votes by members of a federal state do not simply cancel each other out. The government of each federal state is the only body authorised to issue voting instructions. As laid out in the Basic Law, neither the Minister-President (who is entitled to issue guidance within the federal state) nor the parliaments in the federal states may issue such instructions. As a result the governments of the federal states bear parliamentary responsibility and can therefore also be “ousted” by the parliaments in the federal states in response to positions they adopt in the Bundesrat.

Instructions from the governments in the federal states

The votes of a federal state are cast by its Bundesrat members. Generally speaking, the federal state government decides before a Bundesrat session which of the members will cast the votes; alternatively, members decide themselves in the course of the plenary session.

Usually votes are cast by just one member for each federal state, known as the vote-caster. He or she casts all the votes for the federal state in question, even if no other representatives from his or her federal state are in attendance at the meeting. In almost all cases a decision by the federal state government stipulates how the federal state’s votes will be cast in the Bundesrat. However, sometimes the cabinet grants the vote-caster discretionary powers to vote as he or she sees fit, in order to ensure that he or she can reach an agreement with other federal states, has scope to consider possible compromise solutions or can take into account new circumstances that have arisen since the cabinet meeting.

The vote-caster

The Basic Law expects that votes will be cast in a uniform, en bloc manner and respects the practice of vote-casters determined independently by the federal states; it does not encroach on the constitutional prerogatives of the Länder with prohibitions and stipulations on arrangements in this domain. In keeping with a 2002 ruling from the Federal Constitutional Court, this conception of the Basic Law signifies that another member of the Bundesrat from the same fed-

21

Organisation and working methods eral state may at any time object to the votes cast by a vote-caster. In such cases, the fundamental conditions for the vote-caster system to work no longer apply. Should this situation arise in a meeting, the Bundesrat President records the votes of each individual member of the

Bundesrat as a vote for the whole federal state, provided that another member of the same federal state does not cast a contradictory vote. However, if the votes cast by a federal state are not all either in favour of or against a motion (or indeed abstentions), the vote from that federal state is not valid; the divided position of that federal state is not taken into account in the outcome of the Bundesrat vote.

Decisions only with an absolute majority

In the Bundesrat it is not really possible to adopt a “neutral stance” by abstaining from a vote. Pursuant to Article 52 (3) of the Basic

Law, decisions in the Bundesrat may only be adopted with an absolute majority, whilst a two-thirds majority is required for amendments to the constitution. This means that abstaining from a vote is tantamount to voting against a motion – and the substantive impact of this type of vote depends on the balance of all votes cast.

Votes In the Bundesrat voting is generally by a show of hands. Because of the large number of votes to be taken in each session, the Bundesrat

-President generally asks only for a vote in favour of a motion and thus determines if there is a majority or a minority for a motion. In other words, separate voting rounds are not held to count votes against a motion and abstentions, for the distinction between these two voting options is not relevant in establishing whether there is an absolute majority. A “roll-call vote of the federal states” is taken when a vote is held on amendments to the constitution or on other particular important decisions. The federal states then vote in alphabetical order by acclamation. In such cases the votes cast are recorded in the minutes of the meeting. Secret votes are not envisaged in the

Bundesrat’s rules of procedure.

Dieter Althaus,

President of the Bundesrat

(2003/2004)

“We need a reform of the federal system… above all there is a need to correct erroneous developments and recall once again the principles originally spelled out in the Basic Law: subsidiarity and autonomy for the federal states and municipalities, reinforcing these fundamental principles and breathing new life into them.”

22

Organisation and working methods

Plenary sessions

On Fridays at 9.30 a.m. the Bundesrat comes together for its public plenary sessions, which are usually held every three weeks or more frequently. Members take their seats in sixteen blocks of seats. There are no party political parliamentary groups. The seats are arranged in alphabetical order according to the names of the federal states – as are the coats of arms adorning the front wall of the room. Facing the members, on a slightly raised platform, are the

President, the Secretary and the Secretary General of the Bundesrat; members and representatives of the federal government sit to the left and right of them on two longer rows of seats, with a section for Bundesrat staff on the left too. Comments are made from a microphone at the speaker’s desk. The stenographers are seated in front of this desk.

The calm tone usually found in deliberations here is a particular hallmark of the Bundesrat’s plenary sessions. The atmosphere could well be described as cool rather than overheated; people talk calmly and sedately, focussing on the facts. Discussions also remain matter-of-fact in debates with representatives of the Federal Government, even though there are sometimes considerable differences of opinion. Interjections are rare, the meeting never needs to be called to order, and even now when more lively debates are being explicitly encouraged, it is unusual to hear expressions of discontent or applause, which until the 90s were more or less considered poor form.

Matter-of-fact debating style

The generally comprehensive programme of issues to be addressed in the meeting – 40, 50, sometimes even over 80 points on the agenda – is tackled briskly and efficiently. The meeting usually focuses on one or two issues, which are addressed in detail.

Speakers on the other agenda points simply submit declarations explaining and substantiating their government’s decisions. Often these are written declarations, which are not presented orally in the plenary, but are instead simply noted in the minutes and can be consulted subsequently in the session report. Whenever possible, votes on several issues are taken together to save time and ensure that endless individual votes are not required. Usually the President can adjourn the meeting after three to four hours.

Brisk approach to the agenda

23

Organisation and working methods

Impartial The Bundesrat is sometimes referred to as the “House of Lords”, the “Upper Chamber” or as a “well-tempered parliament in which everything is smaller, quieter, more refined”. One could debate whether such descriptions are always accurate; however it is certainly true that efforts to drum up votes or set a particular mood are generally to little or no avail due to the special features of the Bundesrat’s decision-making procedures. Impartiality is therefore one of the prime concerns in the Bundesrat. The rules of procedure take it for granted that members will be cooperative and show consideration in procedural manners, and dispense entirely with provisions on many aspects usually governed by detailed rules in other parliaments. Guidance is provided in these cases by the “customary practice of the assembly”. The idea is to reach agreements in dealing with official business instead of adopting a confrontational approach, as even without specific rules no decision can be attained by “fighting matters out in a vote”.

Careful preparation for votes

While the tone in the plenary may be calm, the meetings are anything but leisurely. Given the plethora of agenda points to be examined, the procedure is so dense and the votes are taken so rapidly that even knowledgeable observers in the public gallery can scarcely keep up. This brisk pace is possible because the meetings, and particularly the votes, are prepared very carefully and precisely. As a result debates are very much focused on the relevant issues, even if the debating style is not exactly spectacular.

The Chamber of European Affairs

Decisions that are to have an external legal effect must be adopted by the Bundesrat plenary session. There is one exception to this general rule: Article 52 (3a) of the Basic Law states that the Bundesrat may create a Chamber of European Affairs for matters concerning the European Union; this chamber’s decisions have the same effect as decisions of the Bundesrat itself. The Chamber deals with urgent and confidential matters pertaining to the European Union, particularly draft legislation. However, so far the Chamber of European Affairs has held very few meetings.

24

Organisation and working methods

It is only convened at the express request of the President of the

Bundesrat. The purpose of this arrangement is to avoid having to arrange special sessions of the Bundesrat. Meetings of the Chamber of European Affairs are public, although it may meet in camera if confidential issues are to be addressed. Each federal state appoints one member of its government to the Chamber, but has the same number of votes in this body as in the plenary. The Chamber is thus a kind of miniature Bundesrat to deal with particular circumstances. It may also adopt decisions without holding a meeting, using an alternative written procedure instead.

The committees

The work done in the committees lies right at the heart of parliamentary activity. Every piece of legislation, whether it is initiated by the Federal Government, the Bundestag or a federal state, is first examined in the committees. Ministers from the federal state ministries, who are well-versed in the subject-matter, or officials from their ministries go through the legislation “with a fine-tooth comb”.

Pooled expertise

Each federal state appoints a member to each committee and has one vote there. The Bundesrat has 16 committees. Their areas of responsibility correspond in essence to the portfolios of the federal ministries.

Thanks to this system the Federal Government’s expertise is directly complemented by that of the Bundesrat and the federal states.

The committees do the groundwork

The heads of the Länder governments generally represent the federal states in the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Defence Committee, which are therefore described as “political committees”.

“Political committees” and expert committees

Committee on

Foreign Affairs

Committee on European

Union Questions

Committee on Health

Committee on

Legal Affairs

Committee on

Defence

Committee on Family and

Senior Citizen Affairs

Committee on

Internal Affairs

Committee on the Envi ronment, Nature Protection and Reactor Safety

Agricultural

Committee

Finance Committee

Committee on

Cultural Affairs

Committee on Transport

Committee on Labour and Social Policy

Committee on Women and Youth

Committee on Urban

Development, Housing and Regional Planning

Committee on

Economic Affairs

Organisation and working methods

In contrast, the ministers in charge of the relevant ministries attend meetings of the expert committees, such as the Committee on Economic Affairs or the Finance Committee. All Committee members may be replaced by “representatives”, i.e. experts from the ministries. This facility is used especially frequently in the expert committees. Some committees almost always meet as civil servant groups. The “representatives” may rotate during the meeting, so that the appropriate experts from the federal states are involved for each specific point on the agenda. In the Committee on the Environment, Nature Protection and Reactor Safety, for example participants might include experts specialised in soil protection, water resources management, protection against dangerous substances, safety in nuclear facilities, waste disposal or emissions abatement.

Practical precision work

The focus in these committees, which are of course not apolitical, is not so much on spectacular matters but instead on practical precision work. The very last details of draft legislation are discussed there; this is where the federal states can help to shape and improve national and European legislation, whilst also exercising scrutiny of such legislation. The good reputation that the Bundesrat committees enjoy is rooted in the rock-solid expert knowledge assembled in the committees, coupled with the experience about enforcement gleaned by the executive in each federal state, as these executive bodies are both close to the citizens and close to the actual impact of implementation.

Civil servants from the federal ministries participate too

Part of the ongoing dialogue between the Federation and the federal states occurs in the committees. The Federal Chancellor and the Federal Ministers are entitled – and at the request of the Bundesrat are obliged – to attend committee meetings (as well as plenary sessions). They have the right to speak at any time. “Envoys of the Federal Government”, i.e. civil servants from the federal ministries, may also attend the meetings. The relevant experts from the national executive and the federal states’ executive bodies all sit together around the same table in the Bundesrat’s committee rooms. Meetings of the committees are held in camera, because discretion is crucial to ensure open and candid discussions, and because confidential matters may be on the agenda.

26

Organisation and working methods

The Mediation Committee

Legislation is developed in a cooperative process involving both the

Bundestag and the Bundesrat. Approximately half of all bills – consent bills – can only enter into force if both assemblies agree. The role of the Mediation Committee is to reach a consensus if there are differences of opinion concerning these bills, or relating to objection bills.

A bridge between the Bundestag and the Bundesrat

This is a joint committee in which the Bundestag and the Bundesrat are equally represented. Each federal state has one seat, and the remaining committee members making up the other half of the group come from the Bundestag, which allocates its seats as a function of the size of the various parliamentary groups. As there are 16 federal states the committee has 32 members. A named alternate is appointed for each member, but alternates may only attend meetings if the member they represent is unable to attend. The purpose of this is to limit the number of participants at the meetings. Each parliamentary group and each of the federal states may replace their representatives at most four times in the course of one legislative term of the

Bundestag. The meetings are strictly confidential. They are conducted by one of the two committee chairpersons, one of them a member of the Bundesrat, the other a member of the Bundestag. The two chairs take turns in chairing the meeting every three months and may replace each other if necessary.

Joint Bundestag and Bundesrat committee

Bundesrat Bundestag

Members of the Committee, including those from the Bundesrat, are not bound by instructions. It would however be unrealistic to believe the Committee could simply disregard the party political balance of power, for the Mediation Committee’s work is only successful if its proposals are ultimately adopted by the Bundestag and the Bundesrat.

Party political balance of power

27

Organisation and working methods

Cases where mediation occurs

The Mediation Committee only becomes involved if it is called upon by the Bundesrat, the Bundestag or the Federal Government to address a particular bill. As a consequence of the various phases in the legislative process, the Bundesrat is automatically the body that generates the most work for the Mediation Committee. The Bundesrat can refer all bills adopted by the Bundestag to the Mediation

Committee. The Bundestag and the Federal Government may only convene the Committee after the Bundesrat has refused to approve a consent bill. A series of three mediation procedures may in some circumstances be required for this category of bills. That is however the upper limit, for each constitutional body is only entitled to refer the same bill to the Committee once.

Proposals

Mediation Committee decisions are taken on a majority basis. All members do not by any manner of means have to support a particular “consensus proposal” – the term used to describe all the Committee’s decisions. In accordance with procedural rules, the mediation process can lead to four different outcomes:

The Committee may recommend that a bill passed by the Bundestag be revised, i.e. that provisions not acceptable to the Bundesrat be reformulated, that additions be made or sections deleted.

A bill passed by the Bundestag may be confirmed. In this case draft amendments submitted by the Bundesrat are rejected.

The proposal may be made that the Bundestag repeal the bill in question. This happens when the Bundesrat rejects a bill in its entirety and succeeds in having this position accepted by the

Mediation Committee.

Mediation Committee proceedings may be concluded without a compromise proposal being submitted. For example, this occurs when it is not possible to reach a majority decision in the Committee as there are an equal number of votes in favour of and against a proposal.

Not a

“super-parliament”

The Mediation Committee may only make proposals to resolve conflicts between the Bundesrat and Bundestag, but cannot adopt bills itself. It is not a “super-parliament”.

28

Organisation and working methods

The Bundesrat’s working methods

There are days when everything is quiet in the Bundesrat. Whilst there is a constant flurry of people coming and going in the Bundestag, the Bundesrat seems to be having a break. But appearances can be misleading. Two factors characterise the Bundesrat’s working methods and make it different from other legislative bodies: the twofold functions of its members and the deadlines set for the most important decisions. As a consequence, the Bundesrat’s work is carried out under permanent time pressure, and is mainly done in the capitals of the federal states and not at its seat in Berlin.

Many centres of activity yet still speedy

In the plenary hall of the

Bundesrat the members are seated in alphabetical order in 16 “Länderblocks” with six seats each. There are no party political groups. The

Secretary and the Secretary General of the Bundesrat sit next to the Bundesrat President to assist him/her in chairing the meetings and counting the votes.

The members and representatives of the Federal

Government sit to their right and left. Other Bundesrat staff also sit on the left-hand side. There are three blocks of seats from which guests of honour, visitors and journalists can follow the proceedings.

Organisation and working methods

Tight deadlines for discussions

The extremely short deadlines set for deliberations on laws – six weeks (in certain cases three or nine weeks) for the first reading, three weeks for the second reading and two weeks for objections

– compel the Bundesrat to work at a strenuous pace. The amendments to the constitution in 1994 did not do away with this time pressure, but simply somewhat alleviated it for the first reading. A new nine-week deadline for opinions was introduced. It applies to bills amending the Basic Law or transferring sovereign rights to the

European Union or international organisations. In addition, the Bundesrat may call for the deadline to be extended from six to nine weeks “for good cause”, particularly if a bill is especially lengthy.

About 13 meetings a year

The dates of plenary sessions are laid down in advance for each calendar year with due consideration to the weeks in which the

Bundestag is in session. About 13 meetings are held each year at three-week intervals. The Federal Government submits its draft proposals to the Bundesrat six weeks before these dates (or three or nine weeks beforehand for the exceptional cases stipulated in the constitution). Drafts from the Bundestag are sent three weeks prior to the plenary session. All drafts are passed on immediately to the appropriate committees. As far as possible they are printed on the day they are received and then distributed to members. The committees must complete their deliberations two weeks before the plenary session. That means that the committees have only three weeks to prepare in the case of draft bills from the Federal Government (in the aforementioned exceptional cases less than one week or six weeks), whilst they have less than a week to consider draft bills from the Bundestag.

Preparation in the federal states

These extremely short deadlines are only acceptable because the committee members and experts from the ministries in the federal states can seek out information from other sources before the draft legislation is received. Nonetheless, the actual decisions can only really be prepared once the committees have received a copy of the draft bill. Prior to the committee meeting, the various ministries in each federal state need to reach an agreement on what their federal state’s position will be; the cabinets in the federal states also have to address the key points in draft legislation at this juncture if the issues are of a political nature.

30

Organisation and working methods

Recommendations for the plenary are drawn up on the basis of intensive discussions in the Bundesrat committees. The secretary of the lead committee compiles these into an official recommendations document, which forms the basis for further decisions in the federal states’ capitals. In formal terms the cabinets in the federal states now have to address all the draft legislation and recommendations included on the agenda of the Bundesrat. However, in practice other civil servant groups work upstream of each cabinet, so that only significant or controversial matters must be decided upon in the cabinet. As well as deciding upon additional motions to be tabled, the cabinets of each federal state stipulate on a case-bycase basis whether the members of the Bundesrat shall be bound by instructions and how votes shall be cast.

Political decisions by the governments in the federal states

Two days before the plenary session, officials in the federal states’ representative offices discuss the meeting once again with senior officials from the Bundesrat Secretariat and the Permanent Advisory Council in the light of cabinet deliberations. At this preparatory stage there is of course also lively contact between the federal states, with a view to finding allies to support their position. A short, confidential meeting of Bundesrat members, known as the “preliminary discussion”, is regularly held immediately before the plenary session.

Search for allies

Decisions on the individual draft bills are adopted in the public session. The Federal Government or other competent bodies are notified on the day of the plenary session and the results of the votes are published subsequently as an official document, along with the minutes of the meeting. Committee deliberations for the next plenary session generally begin again in the week after a plenary session.

Official documents

31

The federal states are entitled to have their say at the federal level, particularly if their interests are affected; that is precisely why the

Bundesrat exists. Although this sounds simple, it is not easy to put into practice.

The next chapter addresses the question of the work carried out by the Bundesrat and the rights it enjoys.

The roles played by the Bundesrat

The Bundesrat – a federal body

The roles played by the Bundesrat

1. Submitting opinions on draft government bills

2. Convening the Mediation Committee

3. Taking decisions on consent bills

4. Participating in addressing objection bills

5. Bundesrat draft bills

6. Statutory instruments

7. Consent to general administrative regulations

8. European Union draft legislation

9. Involvement in dealing with foreign affairs

10. Right to be informed by the

Federal Government

11. Further roles

The roles played by the Bundesrat

The Bundesrat – a federal body

The Bundesrat is a federal body that shares responsibility for overall federal policy. It is not a “chamber of the federal states” (i.e. a body at the federal state level of the system), even though this expression has crept into common parlance. The Bundesrat’s role as a federal body extends exclusively to exercising federal powers and assuming federal responsibilities.

Not a “chamber of the federal states”

The Bundesrat is not responsible for dealing with the functions to be carried out by the federal states. That means it is also not a coordinating body to address problems and concerns that may perhaps be dealt with in a harmonised or coordinated manner by all the federal states. For example, the federal states are responsible for setting the dates for school holidays. It makes sense for the federal states to take a coordinated approach on this question to ensure school holiday periods do not begin at the same time throughout the country, which would cause chaos on the road network and in holiday areas. This kind of “holiday regulation” is adopted by the federal states directly (to be more precise, by the Permanent Conference of Ministers of Education of the Federal States) without any Bundesrat involvement. This type of subject-specific Conference of Ministers exists for all the ministries, as well as for the heads of government of the federal states in the form of the Conference of Minister-Presidents. The Bundesrat makes every effort to ensure its deliberations are not linked to discussions in these subject-specific Conferences of Ministers, in order to prevent the powers and responsibilities of the Federation and the federal states from becoming intermingled; that would blur the distinction between the responsibilities of the various tiers of state even more than is already the case within the “cooperative federalism” system.

The roles played by the Bundesrat

More than a simply advisory role

The Bundesrat’s areas of involvement relate to legislation and administration, as well as to policy on the European Union; in other words the whole sphere of state activity by the federal level in crafting policy. The Basic Law refers in Article 50 to “participation”, but uses this term in a sense much broader than simply a supportive, advisory role of assistance. The participation may involve simply advising the Bun-

34

The roles played by the Bundesrat destag or the Federal Government, but it may also involve playing a much more active role in actually shaping policy and can even signify that the Bundesrat is empowered to take decisions on its own – depending on the details of the individual provisions in the constitution governing this participation.

1. Submitting opinions on draft government bills

In the Federal Republic of Germany most bills are initiated in the form of draft bills from the Federal Government. The Bundesrat has the

“first say” in the parliamentary processing of executive bills. The

Basic Law stipulates that the Federal Government shall first submit its draft bills to the Bundesrat (the draft budget is the only example of legislation that must be submitted to both the Bundesrat and the

Bundestag at the same time). The Bundesrat is entitled to submit an opinion on this draft legislation within a six-week deadline (although in certain cases a deadline of three or nine weeks applies). The Bundesrat makes use of this right in virtually all cases. Review and discussion of legislative proposals submitted by the government are two of the Bundesrat’s primary roles. The experience and insights gleaned by the federal states in the implementation of laws, almost all of which are enforced by them, are incorporated into federal legislation in this first reading. In this context the executive bodies in the federal states conduct an intensive dialogue with the federal executive. The Bundesrat’s checks-and-balances role in the federal system of government is manifested particularly clearly in this setting.

The Bundesrat has the “first say” on draft government bills

The Bundesrat examines the draft bills in its committees, taking all relevant aspects into account: constitutional, technical, financial and political. It often proposes amendments, additions or alternative solutions. Frequently the opinion is simply “no objections”. If a draft bill is rejected in its entirety by the Bundesrat, the Federal Government rarely submits the bill to the Bundestag nonetheless.

At this stage in the legislative procedure, the Bundesrat’s assessment of a bill is not binding on the Federal Government and the Bundestag. However, this initial assessment is an important indicator of

35

The roles played by the Bundesrat what the Bundesrat’s position is likely to be when it has the last word in the second reading. The Bundesrat’s opinions can therefore not simply be ignored. The Federal Government formulates its view on these assessments in a written “counter-statement”. The draft bill, the

Bundesrat’s opinion and the government’s counter-statement are then all submitted to the Bundestag.

2. Convening the Mediation Committee

The President of the Bundestag must submit all legislative decisions adopted by the Bundestag to the Bundesrat. In this second reading, the issue is discussed first of all in the committees, which in particularly assess whether the Bundesrat’s opinion in the first reading has been taken into account and whether or not the Bundestag has introduced other amendments. If the Bundestag’s decision on the legislation is based on a draft bill initiated by the Bundestag only this

“second reading” occurs, even though in that case the term is actually a misnomer.

If the Bundesrat is not in agreement with the version of a bill passed by the Bundestag, it may refer the matter to the Mediation Committee within a period of three weeks. The Bundesrat’s submission to the Mediation Committee, which must be adopted by the plenary session with an absolute majority, includes specific proposals for amendments along with detailed substantiation of these proposals.

3. Taking decisions on consent bills

Bills that have a special bearing on the interests of the federal states cannot become law unless the Bundesrat gives its express approval.

Legislation in this category cannot be passed if the Bundesrat votes definitively against a bill. This rejection of a bill cannot be overturned by the Bundestag. In that case, the only remaining recourse for the

36

The roles played by the Bundesrat

Bundestag and the Federal Government is to refer the matter to the

Mediation Committee in an attempt to reach a consensus. That means that the Bundestag and the Bundesrat must agree on consent bills if legislation is to be adopted.

The provisions of the Basic Law indicate which bills require Bundesrat approval. They can be classified in three groups:

Bills amending the constitution. These require Bundesrat consent in the form of a two-thirds majority vote in favour of adoption.

Bills that have a particular impact on the finances of the federal states. On the revenue side these primarily include all bills relating to taxes for which all or part of the revenue accrues to the federal states or local authorities: for example income tax, value-added tax, trade and motor vehicle tax. On the expenditure side this category comprises all federal bills that oblige the federal states to make cash payments, provide benefits equivalent to cash payments or provide comparable services to third parties.

Bills that impinge on the organisational and administrative jurisdiction of the federal states.