Building better performance: an empirical assessment of the

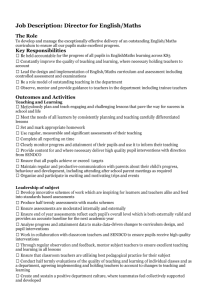

advertisement