Multinational Corporations and Accountability for Human

advertisement

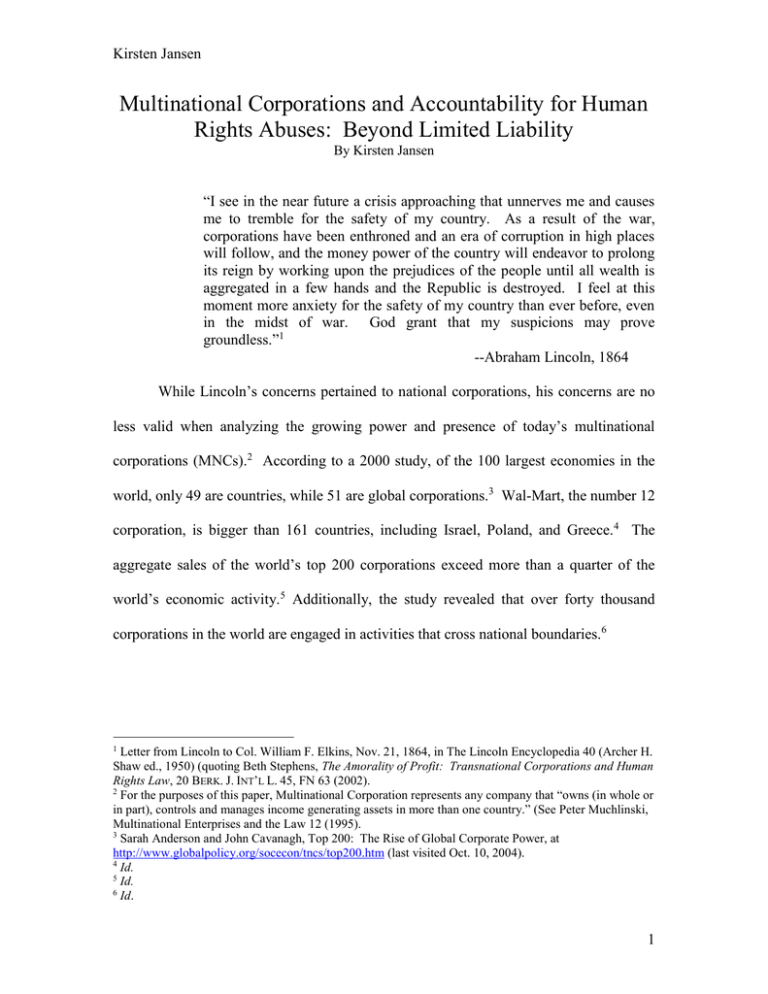

Kirsten Jansen Multinational Corporations and Accountability for Human Rights Abuses: Beyond Limited Liability By Kirsten Jansen “I see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country. As a result of the war, corporations have been enthroned and an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money power of the country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until all wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed. I feel at this moment more anxiety for the safety of my country than ever before, even in the midst of war. God grant that my suspicions may prove groundless.”1 --Abraham Lincoln, 1864 While Lincoln’s concerns pertained to national corporations, his concerns are no less valid when analyzing the growing power and presence of today’s multinational corporations (MNCs).2 According to a 2000 study, of the 100 largest economies in the world, only 49 are countries, while 51 are global corporations.3 Wal-Mart, the number 12 corporation, is bigger than 161 countries, including Israel, Poland, and Greece. 4 The aggregate sales of the world’s top 200 corporations exceed more than a quarter of the world’s economic activity.5 Additionally, the study revealed that over forty thousand corporations in the world are engaged in activities that cross national boundaries.6 1 Letter from Lincoln to Col. William F. Elkins, Nov. 21, 1864, in The Lincoln Encyclopedia 40 (Archer H. Shaw ed., 1950) (quoting Beth Stephens, The Amorality of Profit: Transnational Corporations and Human Rights Law, 20 BERK. J. INT’L L. 45, FN 63 (2002). 2 For the purposes of this paper, Multinational Corporation represents any company that “owns (in whole or in part), controls and manages income generating assets in more than one country.” (See Peter Muchlinski, Multinational Enterprises and the Law 12 (1995). 3 Sarah Anderson and John Cavanagh, Top 200: The Rise of Global Corporate Power, at http://www.globalpolicy.org/socecon/tncs/top200.htm (last visited Oct. 10, 2004). 4 Id. 5 Id. 6 Id. 1 Kirsten Jansen As MNCs grow in number and in wealth, they are gaining commensurate global and domestic political power.7 In response to the enormous power of these institutions and their related potential to commit environmental, labor, and human rights abuses,8 the international community has worked, with considerable success, to establish international treaties, codes of conduct, and other non-binding agreements that impose international norms on MNCs.9 However, the enforcement mechanisms for such norms are currently inadequate10, and the MNC’s ability to insulate itself from liability for human rights abuses is of particular concern in an outdated legal paradigm that addresses an antiquated notion of the corporation.11 While limited liability was developed to encourage middle class investment by limiting individual shareholder liability to the shareholder’s own personal financial investment in a corporation, public corporation law also demanded that shareholders play a strictly passive role and removed them from any role in management. This framework is no longer relevant with respect to the MNC. As Professor Phillip Blumberg notes: 7 See, e.g., Beth Stephens, The Amorality of Profit: Transnational Corporations and Human Rights Law, 20 BERK. J. INT’L L. 45, 57 (2002) (“Economic power carries with it a growing political clout. Corporations play influential direct and indirect roles in negotiations over issues ranging from trade agreements to international patent protections to national and international economic policy.”). See also Joel Bakan, The Corporation, at 27 (2004) (“There has been a transfer of authority from the government…to the corporation, and the corporation…needs to assume that responsibility…and needs to really behave as a corporate citizen of the world; needs to respect communities in which it operates, and needs to assume the self-discipline that, in the past, governments required from it.”)(quoting Sam Gibara). 8 See, e.g., Stephens, at 51-53. (Noting labor violations by Nike; environmental violations by Texaco, Freeport-McMaron, and Shell; and human rights abuses by Unocal Corporation). 9 See Id. at 69-73 (tracing the development of various treaties and agreements targeting MNC conduct). 10 See generally Id. 11 See, e.g. Phillip I. Blumberg, The Corporate Entity in an Era of Multinational Corporations, 15 DEL. J. CORP. L. 283, 285 (1990) (“Corporation Law in the United States (and in other countries as well) is breaking down because of the increasing tension between the conventional view of each corporation as a separate legal entity, irrespective of its interrelationships with its affiliated corporations…and the economic reality of a complex industrialized society overwhelmingly conducted by corporate groups: parent companies, sub-holding companies, and innumerable subsidiaries collectively conducting worldwide enterprises. The predominance of such powerful multinational corporate complexes is creating irresistible pressures for the development of new legal concepts to impose more effective societal controls than those available under traditional entity law reflecting the societies of a century ago.”). 2 Kirsten Jansen The reality of our times, which the law must take into account, is that large multinational corporations with hundreds of public shareholders and corporate structures of ‘incredible complexity’ dominate the modern business world…the law has applied a single body of rules for imposition of shareholder liability without regard to whether the shareholder was an individual or the parent or an affiliated corporation of a giant multinational complex.12 In 2001 Edwin Black published “IBM and the Holocaust,” a book that documents IBM’s involvement, through its subsidiaries, with Nazi Germany and occupied Europe, and his revelations are relevant in this discussion of MNC accountability. 13 In 2002 Black published a second edition of his book14 in which he claims that IBM’s New York headquarters established a completely separate subsidiary in occupied Poland under the name “Watson Business Machines.”15 Black asserts that this subsidiary was directly controlled by its New York parent company.16 IBM’s Polish subsidiary provided Nazi’s with the technology to, among other things, sort and categorize victims transported to the Polish concentration camp Auschwitz.17 IBM was not alone in its dealings with Nazi Germany, 18 and at the heart of all such morally offensive conduct is the pursuit of profit. As one reviewer of Black’s 2001 book pointed out, IBM’s behavior was no different from any other corporation doing business with Nazi Germany, and it “merely demonstrat[es] ‘the utter amorality of the 12 Id. at 287-288. (Blumberg does, however, note that both the courts and the legislature have begun to acknowledge the difference between individual shareholder liability and parent-subsidiary liability, he argues that such developments are in the nascent stages). 13 Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust: the Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation (2001) (herein after Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust). 14 Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation (2002) (hereinafter Black, The Strategic Alliance). 15 Id. at 779. (Kir: check pgs 193 in 1st edition) 16 Id. (Kir: check pgs. 193 in 1st edition) 17 Id. 18 See, e.g. Bayzler and Fitzgerald, supra note 12, at 772 (noting that several U.S. Corporations profited from the business with the Nazi regime, including Chase Manhattan Bank, Standard Oil, Texaco, IBM, ITT, Ford Motor Co., and General Motors). See also Joel Bakan, The Corporation, at 87 (2004) (Discussing General Motors’ German subsidiary Adam Opel AG, which manufactured trucks for the German army). 3 Kirsten Jansen profit motive and its indifference to consequences…many American companies refused to walk away from the extraordinary profits obtainable from trading with a pariah state such as Nazi Germany.” 19 It is increasingly recognized that “[l]arge corporations magnify the consequences of the amoral profit motive. Multiple layers of control and ownership insulate individuals from a sense of responsibility for corporate actions. The enormous power of multinational corporations enables them to inflict greater harms, while their economic and political clout renders them difficult to regulate.”20 One scholar appropriately points out that very few of the executives doing business with the Nazi regime were ever forced to witness the human consequences of that business.21 This note calls for the elimination of limited liability, as it exists today, in the context of MNC tort liability. In an effort to encourage MNC respect for human rights and international norms, this note argues that modern corporate law no longer adequately serves the needs of society, and that while the development of corporate personhood originally focused on corporate rights, the growing power and wealth of the MNC requires a shifting focus on corporate duties. 22 This note argues that enterprise analysis should be used to determine both MNC tort liability and MNC jurisdictional issues under the Alien Tort Claims Act.23 This note also calls for the adoption of a corporate legal paradigm that reflects values beyond profit alone. Though this note makes no argument that corporations should be actively pursuing social causes, it does argue that comparative systems of 19 Stephens, supra note 5, at FN 1. (Richard Bernstein) Stepehens, supra note 5, at 46. 21 Id. 22 Blumberg, supra note 9, at 285. 23 28 U.S.C.A. § 1350 (2000). 20 4 Kirsten Jansen corporate law call for greater social accountability of the corporation, and that such increased accountability is more appropriate in light of the immense wealth and power of the MNCs. Such a paradigm shift, however, necessitates the whole of society’s input, and informed input will require greater exposure to the human consequences of corporate conduct. Part I of this note will explore the evolution of the three distinct philosophies of the corporation as a separate juridicial unit 24 and the concept of limited liability in U.S. corporate law.25 This discussion will provide an economic analysis of limited liability, including the economic objectives of the corporate form and the related reduction in transaction costs through the legal construct of limited liability. However, this note will argue that the current framework fails to address the reality of modern multinational corporations and that limited liability in this context externalizes corporate risks at the expense of involuntary stakeholders. Finally, this section will compare enterprise analysis to entity analysis and argue that enterprise analysis is the more appropriate analysis in the context of MNCs. Part II will explore the Alien Tort Claims Act26 as a vehicle for foreign victims of human rights abuses by U.S. MNCs to gain access to U.S. courts. This section will focus on the challenges such victims face in establishing personal jurisdiction. Specifically, this section will critique the courts’ use of “control” to establish parent-subsidiary liability27, arguing that the concept of control, while applied very rigidly by the courts, is See Blumberg, supra note 9, at 291-299 (discussing the corporation as an “artificial person,” a “contractual” relationship, and a “natural entity). 25 Id. at 322-329. 26 28 U.S.C.A. § 1350 (2000). 27 See, e.g., Timo Rapakko, Unlimited Shareholder Liability in Multinationals, 374-375 (1997) (listing the factors courts consider when analysing parent-subsidiary control as taken from F. Powell, Parent and Subsidiary Corporations, 9 (1931)). 24 5 Kirsten Jansen much too amorphous a concept to allow for any meaningful results. Applying enterprise analysis, on other hand, provides a more concrete result. Part III will examine in greater detail the facts surrounding IBM’s business relationship with Nazi Germany, and in light of the discussions in Parts I-III, it will provide an analysis of how those facts might play out under enterprise analysis in an ATCA litigation.28 Part IV of this note will explore the nature of the corporate duty to maximize shareholder wealth and will confront the human consequences of such a pursuit when the corporation rejects human rights considerations. Part V will offer a conclusion. Part I: The Corporation as a Legal Institution and the Function of Limited Liability A. The Three Theories of the Corporation as a Separate “Juridical Unit”29 While the corporation has received historical recognition as a “separate legal personality” from that of the shareholder, its exact nature as such has often been debated.30 U.S. corporations’ status as a separate legal unit has evolved around three different philosophies.31 Initially, corporations were instruments of the legislature, created and chartered by the legislature for very narrowly tailored purposes, such as the building of railroads.32 As state creations, they “ow[ed] their existence to state action, rather than to the acts of its shareholder-incorporators.”33 There are potential issues here with the decision in Am. Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi, 123 S. Ct. 2374 (2003), in which the court struck down a California statute that threatened to rattle the German settlement program related to the Holocaust. However, that case would not necessarily preclude those from litigating against IBM. 29 Blumberg, supra note 9, at 293. 30 Id. at 291. 31 Id. at 292. 32 Id. 33 Id. 28 6 Kirsten Jansen Under this initial conception of the corporate juridical unit, typically referred to as “artificial person” theory,34 lawmakers and jurists granted “core” rights to corporations, including “the capacity to sue and be sued, to hold and transfer property, to have a time of existence…all separate [rights] from individuals or others who might own its shares from time to time.”35 Beyond these core rights, the corporation had no additional rights but for those granted by the state in its charter, in contrast to the “fuller panoply of legal rights possessed by natural persons.”36 The “artificial person” theory of the corporation gradually gave way to a theory that derived from jurist’s contemplation of the new Constitution, and Supreme Court decisions grew to reflect their consideration of corporate rights in this new constitutional context.37 This second theory, known as the “contract” theory, viewed the corporation as “an association of individuals contracting with each other in organizing the corporation.”38 While the states had previously played a more active role in incorporating organizations, this new theory resulted in a growth of general incorporation statutes, which led to decreased involvement by the state, as incorporation was left to the incorporators and shareholders.39 While this theory provides that the “constitutional Id. Blumberg warns against confusing “artificial” person concepts with corporate personhood, the latter of which is a much stronger “entity” view of the company. He quotes Chief Justice Marshall’s description as an accurate elucidation of the “artifical” person theory he’s discussing: “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of its creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its existence.”(Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 518, 636 (1810). 35 Id. at 286. . 36 Id. at 293. 37 Id. at 294. 38 Id. at 293. 39 Id. Blumberg quotes Justice Field’s elucidation of this theory: “Private corporations are, it is true, artificial persons, but…they consist of aggregations of individuals united for some legitimate business…It would be a most singular result if a constitutional provision intended for the protection of every person against partial and discriminating legislation by the states, should cease to exert such protection the moment the person becomes a member of a corporation.” (The Railroad Tax Cases, F. 722, 743-44 34 7 Kirsten Jansen rights of the shareholders are attributed to the corporation because ‘the courts will always look beyond the nature of the individuals whom it represents,’” it does not follow that the corporation still does not enjoy its historical “core” rights, separate from those of the shareholder, nor did it follow that individual shareholders could somehow invoke those “core” rights.40 The third theory of the corporation as a separate juridicial entity characterizes the corporation as an “organic social reality with an existence independent of, and constituting something more than, its changing shareholders.”41 This view of the corporation is also known as the “natural theory, “the real entity,” or “realism” theory and is the prevailing modern view.42 The “real entity” concept grants corporations their own rights akin to those granted natural persons and separate from and beyond those associated with its state created rights shareholder interests.43 While there is considerable debate over which of these theories should prevail in our legal regime44, the corporation, in fact, embraces all three of these notions, and as one scholar pointed out, “Max Weber came closest to capturing this ambivalence by treating collectivities only as ‘ideas’ in the heads of judges…while at the same time assigning them ‘a powerful, often decisive, casual influence on the course of action of real individuals.’”45 (C.C.D. Cal. 1882), writ of error dismissed as moot sub. nom. San Mateo County v. Southern Pac. R.R., 116 U.S. 138 (1885); Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific R.R., 18 F. 385 (C.C.D. Cal. 1883), aff’d, 118 U.S. 394 (1886)). 40 Id. at 295. 41 Id. 42 Id. 43 Id. 44 Id. (drawing from Teubner, Enterprise Corporatism: New Industrial Policy and the Essence of the Legal Person, 36 AM. J. COMP. L. 130, 138 (1988)). 45 Id. at 295-296 (quoting Teubner, Enterprise Corporatism: New Industrial Policy and the Essence of the Legal Person, 36 AM. J. COMP. L. 130, 138 (1988)) (citing M. Weber, Economy and Society 13 (1978)). 8 Kirsten Jansen However, the adoption of these various philosophies by the courts reflect societal norms at various points in history and have, to a large degree, informed the development of entity law, which in turn has been reinforced through the legal construct of limited liability.46 In fact, this third phase of the corporate juridicial unit viewing the corporation as a “’real entity’ with its own interests transcending those of its shareholders…has dominated corporate law for decades” and has led to the growth in both the number of corporations and the size of corporations.47 However, this “real entity” concept of the law has gone unchallenged while courts have grappled not with the idea of the “real entity” itself, but rather, with just how many additional rights beyond the “core” rights should be extended to it.48 Under the “real entity” view, “[c]orporations have been assumed to be equivalent to each other. The corporation has been seen as the equivalent of the firm conducting the enterprise, and the shareholders as investors not engaged in the conduct of any portion of the enterprise for their direct personal account.”49 While that view may have been relevant in the early development of corporations, such a view is no longer relevant or useful when the law allows for “organization of corporate groups without express authorization by statute or special charter.”50 Of particular relevance to this note is the assertion that when corporations are members of a larger corporate group, the corporation and the enterprise are no longer “identical.”51 The reality of the growth of multinational corporations involving multiple businesses is that the group of corporations forming the enterprise is run “collectively by 46 Id. at 297. Id. 48 Id. at 325 49 Id. at 326 (Bloomberg distinguishes, however, between small corporations where “shareholders may be managers as well as major investors,” and large corporations, where such management by shareholders is not likely to exist.) 50 Id. 51 Id. 47 9 Kirsten Jansen the coordinated activities of numerous interrelated corporations under common control.”52 Under the law, corporations such as Mobil Oil Corporation are viewed as being comprised of hundreds of legally separate corporations, while the reality is that the corporations actually represent a single enterprise acting in a coordinated manner under common control.53 It is this modern disconnect between the law governing corporations and the reality of MNCs that implicates the relevance of limited liability. B. Limited Liability and the Multi-National Corporation 1. History To argue effectively for the abolition of limited liability in the context of MNC tort liability, it is necessary to first analyze the evolution and function of limited liability in American corporate law. In the mid-1800’s, the railway construction business was booming, but the capital investment required for such projects was typically more than the wealthy businessmen, on their own, could provide.54 Therefore, businessmen soon flooded the market with Railway stocks in an effort to fund the construction, and for the first time, middle-class people began to invest in corporate shares.55 However, at that point, the public was also discouraged from investing to that extent that investors were held personally liable, 52 Id. Blumberg notes that while law concerns itself with the separation of the different corporations within the enterprise, economists concern themselves with the economic health of the enterprise as a whole. He also asserts that judicial decisions have grown to reflect this concern with economics, noting that parentsubsidiary relationships have been pierced in tax cases and in stream-of-commerce cases where it was established that the parent participated in the economic activity n question at “an earlier stage” even when such conduct was unrelated by ownership or control. 53 Id. 54 Bakan, supra note 36, at 10-11. 55 Id. at 11. 10 Kirsten Jansen “without limit,” for the company’s debt.56 To fuel industrial expansion, both businessmen and politicians began to lobby for the concept of limited liability, under which an investor’s liability would be limited to that which he or she initially invested, and nothing more.57 Advocates of limited liability claimed that the limitation would attract large numbers of middle class investors to share in the investments of their wealthier neighbors, which would, in turn, “mean that their self respect [would be] upheld, their intelligence encouraged and an additional motive given to preserve order and respect for the laws of property.”58 Critics in both America and England, however, objected to the theory of limited liability on moral grounds. One British parliamentarian spoke out against limited liability, claiming it would vitiate “[t]he first and most natural principle of commercial legislation…that every man was bound to pay the debts he contracted, so long as he could do so,” and that it would “enable persons to embark in trade with a limited chance of loss, but an unlimited chance of gain,” and would lead to a “system of vicious and improvident speculation.”59 Despite these criticisms, limited liability was adopted by legislatures across the nations through the second half of the nineteenth century. 56 Id. Id. 58 Id. at 11-12 (quoting the Select Committee on the Law of Partnership, 1851, B.P.P., VII, vi (as cited in Rob McQueen, Company Law in Great Britain and the Australian Colonies 1854-1920: A Social History, P.h.D. thesis, Griffith University, p. 137)). 59 Id. at 12-13. Bakan also notes Gilbert and Sullivan’s satire of the corporation in Utopia Ltd, in which the lyrics read: “Though a Rothschild you may be, in your capacity, As a company you’ve come to utter sorrow, But the liquidator’s say, ‘Never mind—you needn’t pay,’ So you start another company tomorrow!” 57 11 Kirsten Jansen 2. The Economics of Limited Liability The American corporation operates within a market system. Private property rights are inextricably linked with corporate law and provide a necessary backdrop for the introduction of transaction costs.60 For the purposes of this note, property rights and limited liability will be viewed through the lens of economic efficiency, which, though often criticized as an unsatisfactory social norm, nonetheless provides a useful contrast to strictly moral discussions, particularly since economics, law, and social norms are highly interactive. One scholar suggests that the privatization of property results in reduced transaction costs, which benefit society as a whole.61 He views transaction costs as “crucial element[s] in all legal policy analysis,” asserting that all economic conduct consists of transactions and that each transaction has an associated cost, which include the costs of “finding potential contracting parties…identifying good[s] and/or services in the transaction, [] disclosing terms at which one is willing to deal, [] conducting negotiations, [] drafting the contract, and [] enforcing the contract.”62 The logic behind any contract is that both parties will gain from the exchange and that society on the whole will benefit to the extent that all of these costs are minimized.63 In the context of private property, the shift from communal ownership to private ownership has resulted in reduced transaction costs.64 Property rights essentially consist of two elements: “a right to economic return and a right to control.”65 The economic 60 Rapakko, supra note 43, at 51. Id. at 44. 62 Id. 63 Id. 64 Id. at 51 65 Id. at 52. Rapakko notes however, that Posner has attributed three elements to property rights: universality, exclusivity, and transferability. Rapakko describes that “Universality refers to a situation 61 12 Kirsten Jansen right of return, however, is balanced by the liability of risk that the owner will not see any return, a risk that he did not have to bear when the property was community owned.66 Privatization of property increases “individual risk-bearing” because “individuals switch from bearing an equal portion of the communal risk into bearing personally the total risk with respect to their property.”67 In fact, because property rights impose on owners the risk of unforeseeable events, property law differs significantly from both tort and corporate law, which limit liability to foreseeable risk.68 Any unexpected “hardship” is suffered solely by the private owner rather than shared with the community. 69 However, as noted earlier, the private owner is incentivized to maintain the property and thus glean the returns and profit from any sale, which is said to maximize utility and social welfare.70 The right to control property entails a related obligation on others not to interfere with the owner’s rights, thereby eliminating the problems associated with communal property rights.71 “Thus the difficult issue of how to distribute the jointly owned products is resolved. In the absence of private property rights each member of a community would have to negotiate and contract with all other members.”72 where all resources are owned by someone, the exclusivity to the ability to exclude all others from using property, and the transferability enables the change of property into more valuable uses.” (concepts from R.A. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law 34 (4 th ed. 1992)). 66 Id. at 53. 67 Id. 68 Id. at 55 69 Id. at 54. 70 Id. at 53-54. Tapakko notes, however, that utilization cannot be the sole justification for privatization given the increased risk-bearing and the fact that “incentives can also be provided under a communal property regime through task specialization and by contracts for the specialized tasks.” (54). 71 Id. at 55. 72 Id. at 56. 13 Kirsten Jansen Privatization also reduces the transaction costs associated with “monitoring and enforcement of the community rule.”73 Transaction cost analysis reveals not only that privatization of property results in reduced transaction costs, but also that, with respect to corporations, property rights governance structures are more efficient than communal ownership governance structures.74 Such a discussion, however, must first address the corporate form. While corporate law recognizes a hierarchy that places shareholders on top, the board of directors “subordinated to shareholders,” and management subordinated to the board o directors, economists list the hierarchy in the exact opposite order, concerning themselves more with who controls the organization than who owns it.75 However, property rights in a corporation are intimately connected with risk allocation and risk-bearing among its various stakeholders, and therefore, an analysis of the efficiency of limited liability must begin with a discussion of shareholders. Limited liability was extended to shareholders to fuel investments in otherwise extremely risky ventures.76 Due to the high failure rate of entrepreneurial and small businesses, financing such ventures without the investment of shareholders would require that lenders charge a risk premium that would be prohibitively expensive.77 By granting shareholders the right to invest with limited liability, the legislatures encouraged business investment and growth.78 73 Id. at 57. Id. at 58. 75 Id. at 131. 76 Id. at 142. 77 Id. at 138. 78 Id. (noting that legislative action is always related to social norms). 74 14 Kirsten Jansen Shares of corporations are property rights subject to limitations, for there are multiple stakeholders in corporations, each with interacting rights. 79 The motivation behind this “multi-party property right allocation incorporations” may be the economic incentives which are provided by such rights, and the reduction in transaction costs provided by the ability to contract for such property rights at a low cost.”80 Shareholder’s property rights in a corporation bear the highest financial risk.81 If a corporation fails or is ordered to liquidate, the shareholders are last on the pecking order for recovery of their investment, second to secured debt holders and unsecured debt holders, as represented in the liabilities column on the corporation’s financial statement.82 Additionally, when the value of a corporation fluctuates, those fluctuations are reflected in the share price and suffered or celebrated by the shareholders.83 In exchange for bearing the greatest risk among the corporate stakeholders, the corporate laws also grant shareholders control of the corporate assets.84 However, in large public companies like MNCs, shareholders usually only hold small amounts of equity and play a strictly passive role in the corporation.85 In fact, because shareholders can diversify their risk by investing across a broad range of holdings, ideally limiting their risk to systemic risk, or that associated with general market risk on the whole, control for such shareholders across greatly diversified holdings becomes unmanageable.86 Additionally, shareholders might not have the 79 Id. at 143. Id. 81 Id. at 146. 82 Id. at 145 83 Id. 84 Id. at 146. 85 Id. at 147. 86 Id. at 149-150. 80 15 Kirsten Jansen necessary information to manage specific industries.87 So, while corporate laws “contain the presumption of shareholder control, …shareholders have the right, as gatekeepers, to assign control rights to others, and also to assign the task of allocating such control rights to others,” and in public corporations, the shareholders almost always effect that right.88 The corporate structure of multi-party rights creates a system that significantly reduces transactions costs by allocating and balancing property rights, financial risk, and control rights.89 Specifically, limited liability reduces transaction costs in three vital areas: first, “investor’s contracting costs with co-investors, second, investor’s contracting costs with potential purchasers of their investments, and third, investor’s contracting costs with the business.”90 When a business seeks significant financing, it is unlikely to find all of its financing from a small group of investors, given that investors usually seek to diversify their investments.91 However, if large numbers of investors each had to contract individually with a corporation based on their exposure to unlimited liability, the transaction costs associated with financing businesses would be huge, requiring continuous negotiation on management and insolvency issues.92 For future investors, the shareholder’s limited liability “provides for standardized claims to corporate assets, in the form of shares of a corporation, and enables selling and acquisition of such shares separately from the management of the assets.”93 This in turn creates a liquid market for the shares, which allows shareholders to sell their shares at a 87 Id. at 150 Id. at 149. 89 Id. at 161. 90 Id. at 426 91 Id. 92 Id. at 427. 93 Id. 88 16 Kirsten Jansen cost much lower than if the liquid market did not exist.94 Additionally, limited liability allows the corporation and the co-investors to avoid having to contractually address the insolvency risk, which would otherwise require that the wealthier investors be granted additional compensation with every increase in insolvency risk.95 Limited liability is also economically justified by the fact that, as a general legal and social policy, shareholders are meant to bear the burden of foreseeable risks. 96 Due to the fact that shareholders represent the lowest liquidation priority, as long as shareholders “own a meaningful equity stake in the corporation,”97 the value of that equity will always “reflect the expected business and liability risks.” 98 The logical extension of that idea is that the burden of unforeseeable risks, to the extent they either become foreseeable or are realized, will also be imposed upon the shareholders, in that the equity value will reflect such a revelation.99 However, to the extent that liability never extends to unforeseeable risks, involuntary stakeholders in the forms of individuals or communities “will bear risks of harm for which they may not be compensated.” 100 Rapakko, though, views this inequity as inevitable, pointing out that if neither shareholders, nor corporations or other stakeholders have access to information pertaining to the relevant risk, there may be no single efficient mechanism to regulate and allocate unforeseeable risk, though he also 94 Id. Id. at 428 96 Id. at 424. 97 Rapakko notes that the externalization of risk becomes a moral hazard in situations in which “shareholders do not have a meaningful equity stake” in the corporation, which will provide incentive to “assume a highly risky business strategy on behalf of the corporation.” (425). 98 Id. 99 Id. 100 Id. 95 17 Kirsten Jansen notes that society has created several different regimes to address this issue.101 Even so, it is this externalization of risk that has generated criticism of limited liability, particularly in light of the size and power of the modern MNC. While Rapakko’s analysis vindicates limited liability and provides a nice economic framework within which to consider limited liability, Professor Blumberg and others have noted that the MNC, in which several interrelated businesses are operated for a common good, is in no way analogous to the passive shareholder envisioned when limited liability was adopted. 3. Entity Analysis vs. Enterprise Analysis for Piercing the Corporate Veil In fact, many scholars have argued that limited liability law, originally established to facilitate and encourage individual shareholder investment, was addressed primarily at passive shareholders, while the growing complexity of the MNC concerns a much more actively involved parent company. This development necessitates a move away from recognition of a parent company as an entirely separate legal entity from its subsidiaries.102 These scholars argue that the piercing of the corporate veil cases have yielded entirely inconsistent decisions.103 A move away from entity analysis and towards 101 Id. at 425. See e.g., Blumberg, supra note 9, at 285 (proposing the elimination of unlimited liability for firms within corporate groups); Dent, Limited Liability in Environmental Law, 26 WAKE FOREST L. REV. 151, 178 (1991) (suggesting a “reasonable prudence” test for holding shareholders liable); D. Leebron, Limited Liability, Tort Victims, and Creditors (updated) (Center for Law and Economic Studies, Columbia University School of Law, Working Paper No. 48) (arguing for the elimination of limited liability for corporate subsidiaries); Stone, The Place of Enterprise Liability in the Control of Corporate Conduct, 90 YALE L.J. 1, 74 (1980). 103 David Aronofsky, Piercing the Transnational Corporate Veil: Trends, Developments, and the Need for Widespread Adoption of Enterprise Analysis, 10 N.C.J. INT’L L. & COM. REG. 31 (1985) (drawing from Paul Blumberg, The Law of Corporate Groups §1.02, at 8 (1983)) and (noting a case in which a trial judge stated, “The corporate veil has become a misnomer in modern times…and because the have recognized that a corporate veil may be pierced for one purpose, but not for another, today’s corporation is multi-veiled.”) Amarillo Oil Co. v. Mapco, Inc., 99 F.R.D. 602, 603 (N.D. Tex. 1983)). 102 18 Kirsten Jansen enterprise analysis would create a much more predictable framework for determining when to pierce the corporate veil and impose liability on the parent corporation. 104 A move towards enterprise analysis would not only yield more consistent decisions, but would also reflect the original purpose of the limited liability doctrine, which was to satisfy “[a] practical need…for natural persons to be able to pool their capital into operative business entities while protecting the personal assets of each investor from the unrelated claims of co-investors and of persons dealing with the business entity.”105 While the limited liability doctrine was established to promote capitalism and insulate individual investors’ personal assets from liability, the rationale underlying piercing that veil of limited liability was expressed in Bangor Panta Operations, Inc. v. Bangor & Arrostook:106 “Although a corporation and its shareholders are deemed separate entities for most purposes, the corporate form may be disregarded in the interests of justice when it is used to defeat an overriding public policy.” 107 The concept of “entity” was initially developed to distinguish the corporation as a separate legal unit from that of the corporation’s shareholders.108 However, courts have traditionally extended this distinction to the MNC by insulating the parent company from liability for its subsidiary’s or affiliate’s actions except in rare cases warranting the piercing of the 104 See, e.g., David Aronofsky, Piercing the Transnational Corporate Veil: Trends, Developments, and the Need for Widespread Adoption of Enterprise Analysis, 10 N.C.J. INT’L L. & COM. REG. 31 (1985) (arguing for the use of enterprise analysis in piercing the corporate veil issues involving MNC’s). 105 Id. at FN 7, pg. 33 (quoting Bryant, Piercing the Corporate Veil, 87 Comm. L.J. 299, 299 (1982) (emphasis added)). See generally Blumberg, The Law of Corporate Groups §1.01.1, at 3-4 (1983)). 106 417 U.S. 703 (1974) 107 Bangor Panta Operations, Inc. v. Bangor & Arrostook, 417 U.S. 703 (1974). 108 Id. at 37. The shareholder-investor is distinguished from the shareholder-parent. See also Blumberg, supra note 9, at 327 (noting that “unlike the public shareholder-investors in the modern corporation”…the parent corporation is an active investor and a “major part of the enterprise, engaged along with its subsidiaries in the collective conduct of a common business under centralized control’). 19 Kirsten Jansen corporate veil.109 The trend adopted more recently by some courts and expressed in recent statutes is to eliminate limited liability where it can be shown that “common ownership, direction, and unity of economic purpose among corporate affiliates within the company can be shown.”110 To overcome the burden of this presumption, a corporation would have to prove that its actions and existence within the enterprise were entirely unrelated to the alleged claim.111 The benefits to be realized from such an analysis, it is argued, far outweigh the potential negative effect on investor activity. Greater liability would call for greater accountability and ideally encourage the MNCs to take greater responsibility for their subsidiaries’ activities, rather than shifting the burden to society by evading such accountability.112 Furthermore, such an analysis would conform to the Supreme Court’s ruling that a parent and its wholly owned subsidiary “possess identical legal and economic interests as a matter of law.”113 This shifting of duties and obligations among subsidiary and parent corporations and affiliates is also appropriate in light of the unsatisfactory judicial and statutory approaches to piercing the corporate veil.114 The statutory approach to corporate liability Id. at 37. See also Blumberg, supra note 9, at 288 (noting that “the law has applied a single body of rules for imposition of shareholder liability without regard to whether the shareholder was an individual or the parent or the affiliated corporation of a giant multinational complex; in effect, a ‘shareholder’ is a ‘shareholder’” and that “identical protection has traditionally been accorded to the shareholder who is merely an investor in the corporate business and to the shareholder-parent company in a complex group, which is itself engaged in the conduct of the business of the group, although the relationships of these two very different types of shareholders to the enterprise are universes apart). 110 Id. at 32. But see Blumberg, supra note 9, at 290 (arguing that courts have not gone far enough in their application of enterprise analysis, stating that they “typically attribute certain rights or impose certain duties upon the group…by reason of the activities of its subsidiary only for the purposes of the case at hand, and thus, they do not question the basis of entity law as they still maintain their recognition of the separate corporate existence of the controlled company). 111 Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 32. 112 Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 32. 113 Id. 114 See, e.g., Blumberg, supra note 9, at FN 183, pg. 328 (quoting H. Ballantine, Corporations § 136, at 312 (rev. ed 1946, stating that “The formulae invoked by usually give no guidance or basis for understanding the results achieved.”)). 109 20 Kirsten Jansen in the MNC context turns primarily on the definition of “control,” and perhaps even more importantly, only establishes liability with respect to the issue addressed in that specific statute. The traditional judicial tests usually require the presence of the following three factors to pierce the corporate veil: (1) control of the parent over the subsidiary; (2) inadequate capitalization of the subsidiary by the parent, and (3) the exercise of the control has resulted in a fraud or injustice or the inadequate capitalization has resulted in “fundamental unfairness.”115 The courts may also employ the agency doctrine and impose liability where the affiliate or subsidiary acts as the parent’s agent by doing that which the parent corporation could have done on its own.116 Under this traditional analysis, however, the test to establish control is demanding, and courts will analyze several factors117 to determine whether the subsidiary or affiliate has become a “mere instrumentality” of the parent.118 Rarely is such control found to exist,119 as the courts have traditionally respected the separate legal identities of 115 Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 38-39; Rapakko, supra note 43, at 373-77. Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 40. 117 See Id. at FN 30, pg. 38; See also Rapakko, supra note 43, at 374-75. These factors include: (1) stock ownership by the parent of the subsidiary or affiliate; (2) the sharing of common directors and officers between the parent and subsidiary or affiliate; (3) the extent to which the parent finances the subsidiaries or affiliates activities and the extent to which the subsidiary can function on its own; (4) whether the parent “subscribes to all or most of the capital stock and whether the parent incorporated the subsidiary;” (5) whether or not the affiliate or subsidiary is grossly undercapitalized; (6) whether the prent pays the subsidiary’s or affiliate’s expenses, salaries, and losses; (7) whether or not the subsidiary or affiliate does business solely with the parent company and has no substantial assets but those provided by the parent; (8) whether the parent the parent treats or describes the subsidiary or affiliate as a department or division within the parent corporation; (9) whether the officers and directors of the affiliate or subsidiary can function autonomously from the parent corporation (10) whether the parent corporation has exercised the formal legal requirements of separate legal incorporation; and (11) whether or not the parent corporation treats the subsidiary or affiliate assets as its own. 118 See, e.g. Steven v. Roscoe Turner Aeronautical Corp., 324 F.2d 157, 160 (7th Cir. 1963); Allegheny Airlines, Inc. v. United States, 504 F.2d 104, 112 (7th Cir. 1974), cert. Denied, 421 U.S. 978; CM Corp. v. Oberer Dev. Corp., 631 F.2d 536, 538 (7th Cir. 1980). 119 See, e.g. Lowendahl v. Baltimore & O.R.R. Co., 287 N.Y. S. 62, aff’d, 6 N.E. 2d 56 at 76. (ruling that control required complete domination of business policies and management, and not mere ownership of stock, and that such control must have been used to commit fraud.) 116 21 Kirsten Jansen the parent and subsidiary or affiliate except in cases where that recognition would circumscribe public policy or cause an injustice.120 Conversely, in enterprise analysis, the existence of “control” is presumed, as the coordinated activities of the operations and resources of the affiliates and subsidiaries serve to benefit the entire enterprise or group as a whole.121 Therefore, while the existence of control may be separated from the exercise of control in the statutory context, and while the establishment of control is even more demanding in the judicial context, enterprise analysis argues that such control is, in the context of corporate groups, established as a presumption.122 The application of control to conglomerates, however, presents a different problem. Where the affiliate or subsidiary corporations are engaged in entirely different industries or businesses, such a group demonstrates the potential weakness of the application of enterprise theory to all corporate groups. 123 In this situation, the application of limited liability to parent corporations seems much more in line with the original purpose of the doctrine, as the corporation and all its members are restricted with regards to their access to knowledge and their ability to evaluate risks.124 Even in the context of conglomerates, however, control under enterprise analysis seems to present an efficient model with respect to the corporate group’s exposure to 120 See Mobil Oil Corp. v. Commissioner of Taxes of Vermont, 445 U.S. 425 at 435, 438-41 (1980) (ruling that in certain multinational companies, “many of these subsidiaries and affiliates…engage in business activities that form part of [an] integrated…enterprise…a’unitary business’…[supporting] the conclusion that most, if not all of its subsidiaries and affiliates contribute to appellant’s worldwide…enterprise.”); See also infra, at 22. 121 See Blumberg, supra note 9, at 329-30. 122 Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 331-32. (noting that the exercise of control, where necessary on a caseby-case analysis, turns on the “extent of centralization or decentralization” which, in the context of the corporate group, is no more than “a tactical decision of the moment as to management techniques). 123 Blumberg, supra note 9, at FN 180, pg. 327. 124 Id. 22 Kirsten Jansen liability for the torts of the others.125 Using the presumption of control in the group would necessarily prohibit some corporations from analyzing and “segregating corporate risks.” As such, any blanket application must address this economic inefficiency and demonstrate that the reduction in potential investments would be outweighed by the benefits of imposing liability.126 Where conglomerates are concerned, the blanket imposition of liability for costs arising from “one economic activity upon unrelated activities in other areas” would create the externalization of costs. However, such costs would be limited to only those assets beyond which the perpetrating constituent is unable to cover a tort award of damages.127 Thus, any negative impact would be limited to conglomerates and further limited by the boundaries of the situation addressed above.128 Conversely, in the non-conglomerate scenario, it is highly beneficial to impose liability among the constituent parts of the group for the torts of any of its members, as such liability would force the corporate group, and hence any MNC, to internalize the costs that it was otherwise able to externalize to society.129 Moreover, the availability of insurance may cover such torts.130 In fact, some scholars argue that unlimited liability should be applied to all corporations in the context of tort law, noting the rising value of tort claims and the 125 Id. at 341-42. Blumberg distinguishes between the application of this concept to tort law and other areas of law, suggesting that it may not always be economically efficient to impose liability. 126 Id. at 342. See also Aranofsky, supra note 121, at 43. 127 Id. at 343. 128 Id. 129 Id. See also Henry Hansmann, and Ranier Kraakman, Toward Unlimited Liability for Corporate Torts, 100 YALE L.J. 1879, 1879 (1990-1991) (noting that limited liability creates “incentives for excessive risktaking by permitting corporations to avoid the full costs of their activities,” but that noting also that such incentives are accepted as the price for facilitating capital financing for corporations). 130 Blumberg, supra note 9, at 342. 23 Kirsten Jansen possibility that such claims will exceed the net worth of even the largest corporations.131 When applying unlimited liability to publicly held firms, a categorization under which most MNCs fall, there are several elements to be considered. There are a large number of passive shareholders, a large number of assets involved, and a market for freelytrading stock. There also exists the potential for tort liability to far surpass even the assets of the largest corporations.132 Many economists and lawyers alike have argued that the maintenance of a highly liquid market necessitates the doctrine of limited liability. They argue that the imposition of unlimited liability would not only create unmanageable transaction costs,133 but would also be impossible to administer, without necessarily achieving the desired effect of giving greater incentives to managers to improve firm policy.134 Two scholars have argued that unlimited liability is achievable under an “information-based rule”135 and that collection of such an award would not be prohibitively expensive. This note suggests, however, that the passivity of the individual shareholder-investors and asymmetry of information between the corporate managers and shareholders, somewhat analogous to the conglomerate scenario mentioned earlier, unfairly imposes liability and raises transaction costs substantially. Conversely, the 131 See, e.g., Henry Hansmann, and Ranier Kraakman, Toward Unlimited Liability for Corporate Torts, 100 YALE L.J. 1879, 1880 (1990-1991) (recognizing the potential for mass awards in environmental harms, product litigation, and tort cases and arguing that unlimited liability would “eliminate the inefficient incentives associated with limited liability). 132 Id. at 1894. 133 See, e.g., infra, pgs. 15-20. 134 Id. at 1895. 135 Id. at 1897 (arguing that liability of individual shareholders should attach “at the earliest of the following moments: (1) when the tort claims in question were filed; (2) when the corporation’s management first became aware that, with high probability, such claims would be filed; or (3) when the corporation dissolved without leaving a contractual successor”). 24 Kirsten Jansen MNC exercises control and has access to information such that it should assume liability for the torts of its constituent members.136 Part II: The Alien Tort Claims Act and Multinational Tort Liability 1. Substantive Issues The economic realities governing the global distribution of wealth provide the MNC with incentives to exploit the natural resources, property, cheaper labor, and more lenient environmental and safety regulations often associated with developing countries. In fact, many governments in developing countries are financially motivated to increase foreign direct investment, often at the expense of the health of its citizens. 137 When these citizens become the victims of a corporate tort, there is often little to motivate foreign governments to enforce the rights of their citizens against the corporation, or indeed against the government’s protection and facilitation of that corporation’s conduct. The citizens, in recent cases, have attempted to use the Alien Tort Claims Act to gain access to the American judicial system.138 The ATCA provides foreign citizens with a venue to assert claims against the foreign subsidiary or affiliate of a MNC where such a claim alleges violations of customary international law and where the courts can establish either personal or general jurisdiction over the defendant.139 Though the statute was basically inactivated for nearly 200 years, it was invoked in 1980 after a young man was tortured to death in Paraguay 136 See infra, pg. 26. See Bhopal disaster and Unocal cases, among others. 138 See, e.g. the Unocal case. 139 Beth Stephens, Corporate Accountability: International Human Rights Litigation Against Corporations in U.S. Courts, in Liability of Multinational Corporations Under International Law, Volume 7 at pg. 210 (edited by Menno T. Kamminga and Saman Zia-Zarifi, Klumer International 2000). 137 25 Kirsten Jansen and his family discovered that his torturer had moved to New York.140 The appellate court rejected the lower court’s dismissal and, in Filártiga v. Peňa-Irala,141 ruled that the statute allows aliens to sue for violations of international law around which the court “found an international consensus.” The court then ruled that the torture of a citizen by an official of his government is recognized by the international community as a violation of international law. In 1992, the U.S. Congress enacted the Torture Victims Protection Act (TVPA)142 and extended protection to US citizens under international violations of torture or summary execution. While the statute extended civil remedies to U.S. citizens and endorsed the Filartiga decision, it also required that the underlying violation “be committed under actual or present authority, or color of law, of any foreign nation.”143 However, accountability has been expanded to reach those in a commanding position who “planned, ordered or directed human rights abuses, or who knew or should have known about the abuses and failed to prevent their occurrence or punish those responsible.”144 Though the “commanding position” liability pertains to government officials, an argument can be made that where a corporation wields enormous economic and political influence, the corporation should itself be deemed a State actor. This is relevant to the argument that limited liability should be eliminated in the context of MNC tort violations. The enterprise analysis addressed earlier requires the MNC to take responsibility for all of its members’ tortuous actions, and as such, presumes the parent exerts control. 140 Id. 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980). 142 28 U.S.C. § 1350 (note) (1992). 143 Stephens, supra note 156, at 212 (quoting TVPA, section 2 (a)). 144 Id. at 214. 141 26 Kirsten Jansen Analogously, then, a parent corporation could be held accountable for the actions of its subsidiaries where that subsidiary is acting as a State and the parent is in a “commanding position.” The requisite knowledge would be presumed. In its language directing U.S. federal courts to assert jurisdiction over torts concerning the violation of the “law of nations,” the ATCA has been interpreted to include any violation of international law norms that are recognized as universal, obligatory, and definable.145 Violations recognized under this standard include disappearance, summary execution, prolonged detention, genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, slavery, and “certain acts of cruel inhuman or degrading treatment, and gender violence such as rape.”146 The language of the statute allows for additional claims as norms develop to support such claims.147 U.S. Courts have expanded accountability to include not just public or state actors, but also private actors and private conduct where the international definition of the offense includes private actors and conduct.148 Additionally, U.S. courts have extended the state action obligation to cover private action by following the standards it developed under 42 U.S.C. §1983, the federal statute “defining violations of constitutional rights by public officials.”149 Thus, private action will be attributed to the state when the private actor performs a public function, where the state commands private actors to perform 145 Id at 213 (noting that the standard was first articulated in Forti v. Suarez Mason, 672 F. Supp. 1531 at 1540 (N.D. Cal. 1987). 146 Stephens, supra note 156, at 213. As an aside, it is interesting to note the prolonged detention and degrading treatment elements given the situation at Guantanamo Bay and the Abu Ghraib prison scandal. However, given that the statute protects against violations committed by a foreign nation. 147 Id. 148 Id. at 214-15 (quoting Kadic v. Karadzic, 70 F.3d 232 (2d Cir. 1995)) (ruling that violations by de facto state officials were covered too, as the Torture Convention prohibits acts of torture “inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.” The court went on to note that the State action requirement addresses a regime’s ability to “exert official power over those living under its control, not official recognition.”) 149 Id. at 217. 27 Kirsten Jansen public responsibilities, where the state and private actions are so intertwined as to be undistinguishable, and where the state and private actor are involved in “joint action.”150 Corporations will be liable, just as individual private actors are, when they are either directly responsible for violations of international human rights norms, or when they act in complicity with a government or government officials to commit other human rights violations.151 Additionally, for violations requiring State action, such as torture and summary execution, the corporation will be held liable when it acts in complicity with State actors.152 The State action requirement will be satisfied when the corporation engages in joint action with the government or its official or when it conspires with “or otherwise act[s] in concert with those officials.”153 2. Procedural Issues Foreign citizens seeking access to U.S. courts through the ATCA must still overcome jurisdiction restrictions.154 In order to hear the case, the courts must establish that they have both subject matter and personal jurisdiction over the defendant.155 Subject matter jurisdiction is not much of a hurdle, as state courts of general jurisdiction assert subject matter jurisdiction over almost any claim brought against a defendant over whom they have personal jurisdiction.156 Federal subject matter jurisdiction rules are more restrictive, however, the ATCA grants the federal courts jurisdiction over torts in violation of the law of nations and therefore grants them subject matter jurisdiction over 150 Id. at 217. The argument can also be made that in certain instances, a corporation may actually wield so much influence that the corporation itself ought to be considered the State. 151 Id. at 224. 152 Id. Oxford’s American Dictionary defines complicity as “partnership or involvement in wrongdoing.” 153 Id. at 225. 154 Id. at 220. 155 Id. 156 Id. 28 Kirsten Jansen any claim that falls within the reached of the statute.157 A foreign citizen seeking access to U.S. federal courts can satisfy the subject matter jurisdiction requirement by alleging in her claim “a tort in violation of the law of nations.”158 Personal jurisdiction is more difficult to establish in ATCA cases, and it requires that the court find it has either general or specific personal jurisdiction over the defendant.159 To determine whether or not a court has specific jurisdiction over a defendant, the state courts, though varied in their rules, look to the defendant’s in-state activities.160 The courts will typically analyze both the nature of the defendant’s contact with the state and its relation to the litigation. 161 To determine whether or not a court has general personal jurisdiction over a defendant, the courts look to the defendant’s domicile.162 For private individuals, a court asserts personal jurisdiction over defendants domiciled within the state.163 For corporations, courts assert personal jurisdiction over the defendant’s place of incorporation.164 Additionally, a court can assert personal jurisdiction over a defendant if the defendant is served with a complaint while present in the state.165 A related notion of physical presence applies to corporations when the corporation is “doing business” in a state, and most courts assert jurisdiction over a corporate defendant when it finds the corporation was “doing business” in the state.166 This concept is a murky one, however, 157 Id. Id. at 221. 159 Id. 160 Id. 161 Id. 162 Id. 163 Id. 164 Id. 165 Id. 166 Id. at 222 158 29 Kirsten Jansen and requires a largely case-specific analysis.167 To establish general personal jurisdiction over a parent of a MNC on the basis of “doing business,” the court will consider, among other factors, whether the activities of a subsidiary should be attributed to the parent, and the in-state activities of an agent of the parent.168 Even if all jurisdictional requirements have been satisfied, courts still have discretion to dismiss a case based on the doctrine of forum non-conveniens.169 The Bhopal litigation was dismissed precisely on these grounds, as the U.S. court determined that the deadly events had occurred in India, the victims were located in India, the applicable law was India’s law, and the India courts offered a viable alternative. Often at issue in forum non conveniens dismissals is the applicability of foreign law, the availability of witnesses and evidence, and the availability of a viable alternative.170 In cases involving corrupt governmental regimes, the only path for foreign citizens to achieve justice is through the American court system. PART IV: IBM and Nazi Germany: Liability under Jurisdiction Enterprise Analysis Edwin Black was first struck with the idea for his book while visiting The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum with his parents.171 While there, he was exposed to an IBM Hollerith D-11 sorting machine which used by the Nazi Regime in 1943 to coordinate 167 Id. Id. 169 David Aronofsky, Piercing the Transnational Corporate Veil: Trends, Developments, and the Need for Widespread Adoption of Enterprise Analysis, 10 N.C.J. INT’L L. & COM. REG. 31, at 48 (1985) (Forum nonconveniens gives courts the discretion to dismiss cases that, due to reasons of justice or convenience, should be tried outside of the U.S.) 170 Id. at 49. The argument can be made, however, that to the extent the U.S. courts are exclusively deciding internationa,l MNC tort cases under ATCA, they are also exclusively defining violations of the law of nations, which is probably unpalatable to many sovereign nations, as well as scholars within the U.S. 171 Id. at 11. 168 30 Kirsten Jansen census data identifying Jewish citizens of Germany.172 IBM’s German subsidiary, Dehomag, supplied the Nazi’s with custom-made Hollerith D-11 machines, which utilized punch card technology enabling the Nazi regime to code, track, and identify their various victims.173 For example, the number 12 represented a Gypsy inmate, while the number 8 represented a Jewish inmate, and the code D4 signified “that a prisoner had been killed.”174 Black claims that IBM had full knowledge the Nazi’s were using the technology towards those ends and that it benefited by pocketing the profits made by its German subsidiary during the war.175 Black not only asserts that IBM fully realized all of the profits from this machinery,176 but also that a “senior IBM U.S. representative traveled to Europe to meet with executives there and arranged for a lease of machines to ‘calculate exactly how many Jews should be emptied out of the ghettos each day.’”177 In April of 2001, a class action lawsuit was filed in New York against IBM on behalf of five Jewish survivors, but the suit was dropped when the German government and industry threatened to slow payments to the German Holocaust Fund.178 Interestingly, a Swiss court has recently agreed to hear the case (Geneva was IBM’s 172 Black, supra note 10, at 8. Id. at 9. 174 Gypsies to Sue IBM on ‘Nazi Link’, at http://www.cnn.com/2004/WORLD/europe/06/22/switzerland.ibm.ap. 175 Black, supra note 12, at 778. (Kir- Check pgs. 375-378 of Black book.) 176 Black, supra note 17, at 437. Note, however, that IBM disputed Black’s findings, arguing “We have seen no proof of that…Facts which had been known for many years were used as the basis of allegations in the first book, and they seem to be used in similar fashion in the paperback. We’re not convinced that there are any new findings here.” See Oliver Burkeman, IBM “Dealt Directly with Holocaust Organizers”— Author Says US Firm had Control of Polish Subsidiary, Guardian (London), Mar. 29, 2002. 177 Id. 178 Bayzler and Fitzgerald, supra note 12, at 784 (noting that the suit named as defendants both IBM U.S. and its German subsidiary. German companies sought insulation from legal actions before committing to the fund) (IBM’s German subsidiary ended up paying $3million into the fund but denied that such a payment constituted liability) (See Anita Ramastary, A Swiss Court Decides to Allow Gypsies’ Holocaust Lawsuit to Proceed, at http://writ.findlaw.com/ramastary/20040708.html. (last visited Oct. 10, 2004) 173 31 Kirsten Jansen European headquarters during WWII).179 The plaintiffs in the case are four Gypsies from Germany and France, all of whom were orphaned “in the Holocaust after losing family members in death camps.”180 At least 600,000 gypsies died in the Holocaust, and the lawsuit “alleges that IBM aided and abetted the mass slaughter of gypsies by knowingly allowing the Nazis to use its punch-card Hollerith tabulating machines to code, track and identify Gypsy victims.”181 While a lower court dismissed the case due to lack of jurisdiction, the Swiss appeals court reversed the decision and concluded that “IBM’s complicity through material or intellectual assistance to the criminal acts of the Nazis during World War II via its Geneva office cannot be ruled out,”182 and “a significant body of evidence indicat[es] that the Geneva office could have been aware that it was assisting these acts.” According to one prediction, the “suit will turn on whether IBM was responsible for the way its machines were used during the Holocaust.”183 Interestingly, the Swiss court notes that IBM could have been complicit by providing intellectual assistance to the Nazis through its Geneva offices. In a way, this logic is analogous to enterprise analysis in that the Geneva office is seen as one office in the enterprise, an enterprise in which every constituent part is there to benefit the success of the whole. In applying enterprise analysis to IBM and its subsidiaries, the parent corporation is deemed to have “controlled” the subsidiary for the purposes of liability for any of its subsidiaries’ wrongdoing. This seems entirely appropriate in light of Mr. Black’s book, which reveals that even though IBM had many subsidiaries throughout the Anita Ramastary, A Swiss Court Decides to Allow Gypsies’ Holocaust Lawsuit to Proceed, at http://writ.findlaw.com/ramastary/20040708.html. (last visited Oct. 10, 2004) (I say interesting because this may be the first time that an action alleging human rights violations by a corporation in WWII was commenced outside of the U.S., which carries with it broad implications for future human rights cases). 180 Id. 181 Id. 182 Id. 183 Id. 179 32 Kirsten Jansen world, Mr. Watson, IBM’s CEO, was actually in correspondence with many of them.184 Certainly, as his correspondence reveals, Mr. Watson was very much involved with making sure that the subsidiaries were feeding profits back into IBM. 185 Even when, due to America’s declaration of war, it became impossible for IBM to directly do business with some of its Eastern European subsidiaries, Black claims that IBM was still able to influence these subsidiaries by keeping in close contact with its subsidiaries located in neutral countries.186 The foreign victims of Nazi Germany could file claims against I.B.M. N.Y. and its German subsidiary here in the U.S. by alleging “torts in violation of the law of nations.” This would grant federal courts subject matter jurisdiction to hear the case under several of the internationally recognized violations of international norms, including prolonged detention, genocide, war crimes against humanity, slavery, and cruel inhuman treatment.187 It could do so under ATCA by showing that the subsidiary acted in “complicity” with Nazi Germany officials, as Black documents I.B.M.’s subsidiaries knowledge of Nazi use of its technologies.188 Additionally, for those violations requiring State action, including torture, the victims could certainly allege that the subsidiaries conspired with the Nazi regime or “otherwise act[ed] in concert with those officials.”189 Personal jurisdiction over I.B.M. would be easy to establish, since it is incorporated in the U.S.190 However, that does not eliminate the possibility of dismissal due to forum non conveniens, and here, enterprise analysis might aid plaintiffs seeking 184 See, e.g. Black, supra note 10, at 166, 180. Id. 186 Id. at 376. 187 See infra, pg. 28. 188 See, e.g., Black, supra note 10, at 377-381. 189 See infra, at 28. 190 It should be noted that the issue of personal jurisdiction is increasingly relevant where the MNC is headquartered and incorporated elsewhere in the world, and its subsidiary in the U.S. is being sued. 185 33 Kirsten Jansen access to U.S. courts.191 Courts applying enterprise analysis will “presume that it is neither unfair nor inconvenient to attribute the conduct or status of one corporate entity to all of its affiliates who actions are relevant to the litigation.”192 Similarly, courts would presume that the parent controlled the subsidiary.193 Ultimate liability would most likely rest on this issue of I.B.M’s control over its subsidiaries (provided the subsidiary itself is found liable), and because the traditional judicial tests are unrealistically demanding and formalistic in light of today’s corporate realities,194 enterprise analysis is more appropriate framework in which to consider liability. Because IBM’s German subsidiary was one constituent part of a larger I.B.M. whole, and because all of the operations ultimately fed profits back into the enterprise, control is to be assumed, and to the extent the subsidiary is liable, I.B.M. itself would be held liable.195 Though Black blames I.B.M.’s C.E.O. Thomas J. Watson for I.B.M.’s dealings with the Nazi regime, he also believes that “Watson didn’t hate the Jews. He didn’t hate the Poles. He didn’t hate the British, nor did he hate the Americans. It was always about the money.”196 PART IV: Tempering the Pursuit of Profit There are many economists who would argue that I.B.M. and its subsidiary were conducting themselves as any corporation should. Corporations, after all, have a duty to 191 David Aronofsky, Piercing the Transnational Corporate Veil: Trends, Developments, and the Need for Widespread Adoption of Enterprise Analysis, 10 N.C.J. INT’L L. & COM. REG. 31, at 49 (1985) 192 Id. 193 See infra. 194 See infra, pg.21, FN 118. 195 See infra, pgs. 30-33. 196 Oliver Burkeman, IBM “Dealt Directly with Holocaust Organizers”—Author Says US Firm had Control of Polish Subsidiary, Guardian (London), Mar. 29, 2002. 34 Kirsten Jansen maximize shareholder wealth.197 Government itself, they argue, must regulate corporations when that pursuit of profit creates unacceptable results. For example, Milton Friedman, a world-renowned economist, argues that “the social responsibility of business is to increase profits.”198 Likewise, in an interview with Joel Bakan, Friedman stated, “A corporation is the property of its stockholders. Its interests are the interests of its stockholders. Now, beyond that, should it spend the stockholders’ money for purposes which it regards as socially responsible but which it cannot connect to the bottom line? The answer I would say is no.”199 Anita Roddick, unique in her roles as both founder of The Body Shop and social activist in the world at large, rejects Friedman’s analysis, blaming the “religion of maximizing profits” for the legitimization of all activities in its pursuit, including the use of child labor, the use of sweatshop labor, the destruction of the environment, etc.200 Friedman and Roddick, however, perhaps inhabit two extremes of the spectrum in the debate on the utility of profit. While this note does not argue that profit is either inherently moral or inherently immoral, it does argue that the pursuit of profit cannot be valued, nor should it be legally mandated, at the expense of human rights. While Friedman bristles at the idea of using stockholder money to achieve socially responsible goals, it does not necessarily follow that he believes human rights should be sacrificed in the pursuit of profit. The behind-the-scenes profit calculations conducted by many corporate executives evidences, to an alarming degree, just how far corporations will go in pursuit 197 See infra, pg. 35. Id. at 62. 199 Joel Bakan, The Corporation, at 34 (2004). 200 Id. at 55 198 35 Kirsten Jansen of such profit. For example, in 1993 General Motors was sued when a woman driving a Chevrolet was rear-ended, causing the fuel tank to explode, leaving her and her four children severely burned and disfigured.201 During the trial, it was revealed that the fuel tank had been positioned just eleven inches from the bumper.202 General Motors, it turned out, was aware of the dangers presented by such positioning. 203 A 1969 directive had recommended fuel tanks be places at least seventeen inches from the tank.204 When GM designed its subsequent models, however, the tanks were placed much closer to the fuel tank and by the early 1970’s there had been over 30 fuel-fed fire lawsuits.205 Still, GM designed the model that positioned the fuel tank just 11 inches from the bumper.206 Sometime in 1973, GM commissioned one of its engineers from the design division to analyze the fuel-fed fires.207 In his report, the engineer estimated the potential legal cost of each potential fatality and compared that against the cost of moving the fuel tanks.208 He calculated the following:209 500 fatalities x $200,000/fatality = $2.40/automobile 41,000,000 automobiles The cost of making sure the fuel tanks did not explode was $8.59 per automobile.210 The engineer then subtracted the cost of each fuel fatality to arrive at a total savings of $6.19 per automobile if it allow people to die rather than adjust the tank.211 The jury found 201 See Bakan, supra note, at 61. Id. at 62. 203 Id. 204 Id. 205 Id. 206 Id. 207 Id. 208 Id. at 63. 209 Id. 210 Id. 211 Id. 202 36 Kirsten Jansen GM’s behavior to be morally deplorable and awarded the victims in the suit, Mrs. Armstrong and her children, $107 million in general damages and $4.8 billion in punitive damages.212 The judge ruled, “The court finds that clear and convincing evidence demonstrated that defendant’s fuel tank was placed behind the axle on automobiles of the make and model here in order to maximize profits- to the disregard of public safety.”213 These calculations are devoid of any exposure to their human consequences, tough once the jury was exposed to them, the corporation was compelled to change. The lack of exposure to human consequences of corporate conduct is magnified in the context of MNCs, where subsidiaries are often doing work in developing countries. The potential harms inflicted, then, can often go unnoticed but for the most publicized disasters. The greater exposure we, as a society, have to these consequences, the greater likelihood that we will compel corporations to change, and perhaps through a change in law. Conclusion It is undisputable that MNCs are amassing increasing wealth, power, and political influence internationally. Corporate law, however, has not evolved commensurately to adequately address this reality. Limited liability was and still is a useful tool to spur capitalism and encourage capital investment. However, it was aimed at individual personal investors who remained passively involved in the corporation. MNCs are not individual persons, nor are they passively involved in corporate management. By insulating parent corporations from the tortious conduct of its subsidiaries, limited liability externalizes the cost of harmful corporate conduct onto society at large, which is an involuntary stakeholder in the corporation. Though U.S. labor and environmental 212 213 Id. (This award was later reduced) Id. at 62. 37 Kirsten Jansen regulations and laws address some of this externalization in the U.S., it cannot necessarily do so internationally, and most international codes of conduct governing corporate conduct are non-binding. To address this disconnect, limited liability should be eliminated in the context of MNC torts, and instead, the courts should apply enterprise analysis, which would presume a corporation’s control over its subsidiary and encourage accountability. This change, however, may only come about when society as a whole is exposed to the human consequences of unchecked corporate conduct. 38