STATE OF VERMONT PUBLIC SERVICE BOARD Docket No. 5983

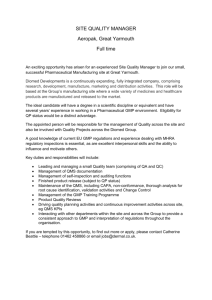

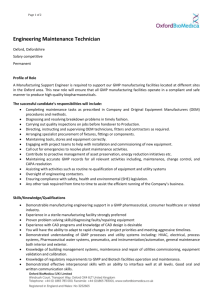

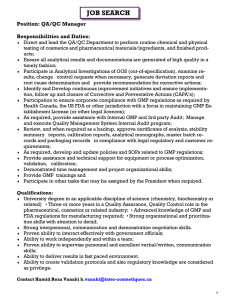

advertisement