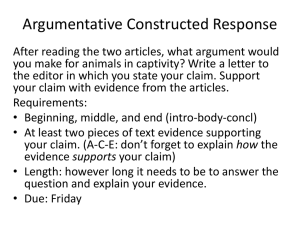

The New York Times 1

CLAIM

EVIDENCE

INTERPRETATION

Annotate for

Claim, Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

July 5, 2012

The New York Times: Room for Debate

Does Captive Breeding Distract From Conservation?

PART OF CLAIM

Through research, luck, and trial and error, zoos are learning some tricks for breeding endangered animals in captivity . But with so many species, like pandas and cheetahs, it’s no sure bet, and it isn’t cheap.

Are conservationists and zoos trying to keep too many species alive in captivity? Would the money be better spent in other ways — on protecting habitats, or on collecting and preserving tissue samples and seeds, or on

“rewilding”?

Protect and Restore Animal Habitats

Debater #1: Reed Noss, Provost’s distinguished research professor at the

University of Central Florida and president of the Florida Institute for

Conservation Science, is the author of the forthcoming "Forgotten Grasslands of the South: Natural History and Conservation."

Updated July 5, 2012, 11:41 AM

Conservation problems take many forms; therefore, so must solutions. That said, because the loss, destruction and degradation of habitat is the major cause of the extinction crisis – driven ultimately by human population growth and over-consumption of resources – the protection and restoration of habitat for native species is the most important thing we must do to save species.

Scientific estimates suggest that if we are to reduce extinction rates appreciably, at least half of a typical region must be protected and managed with conservation of biological diversity as a major goal. This scale of protection will not be possible without a large reduction in the human footprint, that is, scaling back our population and consumption.

Many zoos already contribute to habitat conservation, but the scale of these efforts must be expanded.

Do zoos have a role to play in this solution? Certainly. Many zoos already contribute to habitat conservation, but the scale of these efforts must be expanded. Zoos also should better educate the public about proximate and ultimate causes of species loss. With climate change, the role of captive populations in zoos becomes more important. Many species – for example,

Annotate for:

1

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

ETHOS OF THE

SOURCE

(Professor and

ScientisT)

EVIDENCE ON

SPECIES

AFFECTED BY

RISING OCEANS =

LOGICAL = LOGOS

1

BACKGROUND TO

CONVERSATION &

CLAIM

EVIDENCE

INTERPRETATION

Annotate for Claim,

Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal on islands soon to be inundated by the rising oceans

– will soon lose all of their habitat in the wild. We must take these species entirely into captivity, move them to a new habitat (often not a good idea), or freeze samples of their tissues in gene banks. The alternative to these measures is simply to document their extinction in the wild.

EVIDENCE

INTERPRETATION

COUNTERARGUME

NT (THEY SAY)

Many species in the Florida Keys, like the Key deer (about the same size and attitude as a skinny Labrador retriever), will go extinct in the wild within the next few decades as their habitat disappears under the sea. Educational exhibits with Key deer in zoos will provide a valuable lesson to the public about how human-induced climate change has driven species to the brink of extinction. The alternative to taking Key deer into captivity would be relocating them to Caribbean islands similar to the Florida Keys, but but they would not be native there, so I am not convinced this is a good idea. They might have unanticipated negative effects on native species.

REBUTTAL/INTERPR

ETATION

EVIDENCE

INTERPRETATION

Interestingly, the Key deer evolved as its island habitat became isolated by rising sea level since the last glacial maximum. Only over the last 6,000 years have the Florida Keys been isolated from the mainland, and the Key deer has evolved in genetic isolation from mainland deer populations. Soon these islands will largely disappear, this time under a sea rising because of human activity. That’s a lesson in evolutionary biology as well as in climate change and conservation.

EXIT – MATCHES

CLAIM

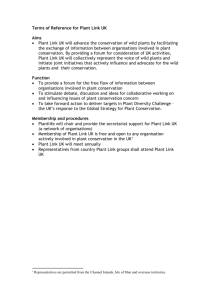

Humans Can Manage Wild Animal Populations

Debater #2: Antoinette Kotze is the manager of research and scientific services at the National Zoological Gardens of South Africa.

Updated July 5, 2012, 11:10 AM

Biodiversity is threatened by many changes: habitat loss and degradation, pollution, invasive alien species and global warming. No single solution can address these. Therefore the National Zoological Gardens of South Africa takes a holistic approach toward conserving species and maintaining ecosystem integrity.

Lions are an excellent example of the importance of both research and intervention to protect a species. Free-roaming lions found in Africa are threatened by human encroachment, and the wild populations continue to decline. If this decline cannot be stopped or reversed, zoos may have an increasingly important role in the conservation of these magnificent animals.

ETHOS OF

SPEAKER: WORKS

FOR NATIONAL

ZOO

EVIDENCE BASED

ON LIONS (ONE

CASE STUDY) =

LOGICAL = LOGOS

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

EVIDENCE ON

SPECIES

AFFECTED BY

RISING OCEANS =

LOGICAL = LOGOS

2

Annotate for:

Claim, Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

EVIDENCE

INTERPRETATION

EXIT – MATCHES

CLAIM

Before the situation becomes that dire, however, scientists are working to maintain and build up the wild populations.

Lion populations in South Africa show the value of humans being very involved — if need be, even choosing mates and using artificial insemination.

Lions’ history in South Africa is unique. They were extirpated from much of their historical range in South Africa by the 1900s, with only a few viable populations remaining. In the early 1990s, lions were reintroduced into about

40 fenced reserves and, because of fences and human management, these lion populations are growing. This proves the potential of humans being involved in wild animals’ lives — sometimes very involved. In a collaborative project, the National Zoological Gardens and others recently improved a semen collection method for wild felids to yield high sperm quality in African lions. This allows us to assess fertility, bank genetic material and, if need be, assist reproduction in the wild with artificial insemination.

3

Annotate for:

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

When humans are choosing sperm sources and artificially inseminating a wild lion, is that in situ conservation (in the wild) or more like captive breeding? The line is blurring. As the anthropologist Diana J. Pritchard and her co-authors wrote in January

, “the relentless loss of the ‘wild’ may soon render the in situ / ex situ distinction misleading.”

We Need Every Approach to Save Animal Habitats and Species

Debater #3: George Amato is director of the Center for Conservation

Genetics at the American Museum of Natural History.

Updated July 5, 2012, 11:40 AM

While the debate about the value of captive breeding has been acrimonious, most conservationists agree that it has a role. The dispute stems from some proponents’ exaggerated (and unrealized) claims about the potential of captive breeding, and others’ campaigns for financing that treat conservation as a zero-sum game. But as species continue to hurtle toward extinction, there will be a greater need for this and other intensive management strategies.

This disagreement boils down to three related questions: First, what should be the role of captive breeding in conservation? Second, are zoos using captive breeding as an effective conservation strategy? And third, are

3

Annotate for Claim,

Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

4 conservation resources limited and competing — and would they be better spent on other conservation strategies?

Annotate for:

We should focus on both habitats and species, and preserve biodiversity in the wild and in captivity and gene banks.

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

None of these are new questions. I’m reminded of the Bill Murray character in

“Groundhog Day” — condemned to relive the same day over and over until he

“gets it right.” We seem to have this debate over and over, while the urgency only grows. A dozen years into this new millennium, we still have not seen a change in the trend toward catastrophic loss of species and habitats worldwide.

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

Certainly the most effective conservation will take place in the remaining landscapes and seascapes that are least affected by humans. But there is no clear delineation; few places are “untouched.” Thus we must combine good science and good public policy to retain maximum biological diversity across all environments, from urban to rural.

If we are to be successful in saving even a small number of critically endangered species, they will need to be intensively managed, both in their natural habitat and in captivity. In general, captive breeding is not very important to conservation — but for a few species on the critical list, including some extinct in nature, it is the only viable option. The effectiveness varies widely; success depends on programs being scientifically managed, and carefully linked to efforts to build up populations in what remains of that species’ more natural habitat.

Zoos have often been described as the logical places for effective conservationrelated captive breeding, and there are a few examples of successes. But largely zoos have not lived up to their potential for conservation. The modern zoo seems uncertain about its mission. Too often, zoos are understaffed and too much is asked of zoo professionals in terms of animal management and welfare and guest experiences, leaving conservation as an afterthought. Zoos still struggle to keep self-sustaining populations for exhibition, giving conservationists little optimism about captive breeding for conservation and reintroduction into the wild. Perhaps this will change when zoo boards, administrators and the public see a greater need for meaningful conservation.

Science-based conservation needs to expand its realm and not look to constantly reargue competing priorities. We need every approach, including programs focused on habitats and others focused on species. We need ecology and genetics and behavior and health studies. We need to ameliorate identified threats in nature and also retain insurance populations and bank genetic resources (one of the priorities of the Center for Conservation Genetics at the

American Museum of Natural History). Only in this way can we end

“Groundhog Day” and change the trajectory of the catastrophic loss of biodiversity.

4

Annotate for Claim,

Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

ESSENTIAL

QUESTION

COUNTERCLAIM/RE

BUTTAL (THEY

SAYS!)

***OCCASION:

WHERE & WHEN

EXIGENCE (SOCIETY

EVENT)

Smart, Social and Erratic in Captivity

By JAMES GORMAN JULY 29, 2013

The New York Times

Should some of the most social, intelligent and charismatic animals on the planet be kept in captivity by human beings?

That is a question asked more frequently than ever by both scientists and animal welfare advocates, sometimes about close human cousins like chimpanzees and other great apes, but also about another animal that is remarkable for its intelligence and complex social organization — the killer whale, or orca.

Killer whales, found in all the world’s oceans, were once as despised as wolves. But in the last half century these elegant black-and-white predators — a threat to seals and other prey as they cruise the oceans, but often friendly to humans in the wild — have joined the pantheon of adored wildlife, along with the familiar polar bears, elephants and lions.

With life spans that approach those of humans, orcas have strong family bonds, elaborate vocal communication and cooperative hunting strategies. And their beauty and power, combined with a willingness to work with humans, have made them legendary performers at marine parks since they were first captured and exhibited in the 1960s. They are no longer taken from the wild as young to be raised and trained, but are bred in captivity in the United States for public display at marine parks.

Some scientists and activists have argued for years against keeping them in artificial enclosures and training them for exhibition. They argue for more natural settings, like enclosed sea pens, as well as an end to captive breeding and to the orcas’ use in what opponents call entertainment and marine parks call education.

Now the issue has been raised with new intensity in the documentary film

“

Blackfish

” and the book “Death at SeaWorld,” by David Kirby, just released in paperback.

The film and book both focus on the 2010 death of Dawn Brancheau , a trainer, at SeaWorld in Orlando, Fla. She was dragged underwater by a whale called

Tilikum, who had been involved in two earlier deaths.

5

Annotate for:

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

PANTHEON: group of powerful things (Gods)

The event led to two citations for safety violations by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration for an unsafe workplace, and an ongoing struggle over OSHA requirements that trainers be separated from killer whales. The most recent fine was in June, and SeaWorld is appealing both decisions.

5

Annotate for Claim,

Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

Both the book and film argue that Tilikum’s actions were deliberate and that his behavior was a result of the psychological damage of captivity, not just at

SeaWorld but also at another facility where he was first kept. SeaWorld has said the death was an accident, not a deliberate killing.

6

Beyond the death of Ms. Brancheau and the arguments over how SeaWorld manages its many facilities lies a fundamental disagreement about whether killer whales, and other cetaceans — the group of marine mammals that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises — should be held captive at all.

Annotate for:

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

It is reminiscent in many ways of the movement to put all captive chimpanzees into sanctuaries, which recently scored two major successes when the National

Institutes of Health decided to retire most of its chimpanzees and the Fish and

Wildlife Service proposed listing all chimps as endangered, raising new barriers to experimentation.

But the situation for killer whales is different. There are many fewer in captivity

— a total of 45 worldwide, according to the organization

Whale and Dolphin

Conservation — and thousands of people have come to love them partly because of the very exhibitions in marine parks like SeaWorld that disturb those who oppose keeping the whales in captivity. A great deal of scientific study of marine mammals has also been done in these marine parks.

But even some scientists who have worked with captive dolphins set orcas apart because of their size, their range of movement in the wild, and the close-knit nature of their social groups.

Diana Reiss of Hunter College, who has studied self-recognition in captive dolphins and who was not involved in the making of “Blackfish,” said that the question of whether animals like bottlenose dolphins should be kept in captivity is important and should be discussed.

But, Dr. Reiss said, she does not see ambiguity about killer whales. “I never felt that we should have orcas in captivity,” she said. “I think morally, as well as scientifically, it’s wrong.”

The animal in question, Orcinus orca, is actually the largest dolphin. Its name apparently came not because it was a vicious whale, but because it preyed on whales.

The species as a whole has a varied diet, with some groups specializing in fish eating, and others concentrating on seals. They have been known to eat penguins and other seabirds, occasionally squid and turtles, even a swimming moose or deer.

The males can reach 32 feet long and weigh up to 22,000 pounds . The females are smaller, up to 16,500 pounds, but live longer. While males average about 30 years and may reach 60, females normally live about 50 years but can reach 90.

6

Annotate for Claim,

Evidence,

Interpretation

(Analysis),

Counterclaim,

Rebuttal

They live in family groups or pods, typically ranging from a couple of animals to 15, although they may temporarily join in groups of 200 or more.

7

They exist around the world, and subgroups differ in diets, behaviors and physical traits. One subgroup in the Pacific Northwest, called the Southern

Resident population, is listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered

Species Act.

Orcas can travel great distances. “They can go 100 miles in a day,” said Lori

Marino , an Emory University researcher who worked with Dr. Reiss and an activist, who appears in “Blackfish” and opposes keeping dolphins and orcas in marine parks.

Annotate for:

1) Appeals to

Logos, Pathos,

Ethos

2) New Vocab

3) Questions &

Responses

Killer whales have complex brains, and the behaviors of different groups are so diverse that scientists talk about them as having different cultures.

The opposition to keeping them in captivity is based partly on evidence that they are smart, social and wide ranging. Those facts are not really disputed, nor is the principle that humans owe the orcas now in captivity a good life.

Opponents of captivity cite a number of physical and psychological problems, including repetitive behaviors, dental issues and attacks on trainers, like the one on Ms. Brancheau.

Yet opponents of captivity recognize that the animals, for their own safety, cannot simply be released into the wild, and so are not calling for SeaWorld or other marine parks to close. Rather, they say, they would like to see the parks keep the orcas in larger, more natural settings, something like sea pens

— inshore areas of ocean that can be closed in by nets.

Naomi Rose , a whale biologist who is moving from the Humane Society of the United States to the Animal Welfare Institute , was a co-author of a

Humane Society paper in 2011 opposing the keeping of orcas in captivity.

She said creating sanctuaries for orcas is “highly feasible,” and could and should be done by companies like SeaWorld, which has 22 orcas, nearly half of the total in captivity.

Merlin Entertainment, which owns amusement parks like Legoland and some

Sea Life aquariums, mostly in Europe, has been exploring the possibility of a sanctuary for bottlenose dolphins with Whale and Dolphin Conservation.

Cathy Williamson, the captivity program manager for the organization, said it had been “quite tricky” finding a location in Europe where a large natural area, a cove or bay, could be enclosed. Yet, she said, it is feasible to create “a very large netted area, so they’re still in captivity, but they wouldn’t be performing tricks for tourists.” The same kind of sanctuary could also work for orcas, she said.

7