Accounting for Performance in Contracting for Services:

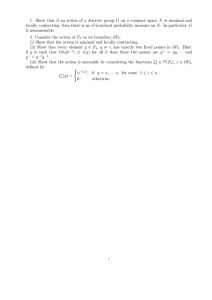

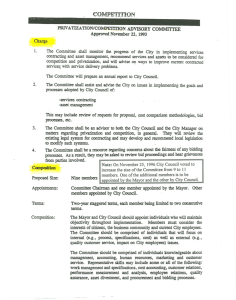

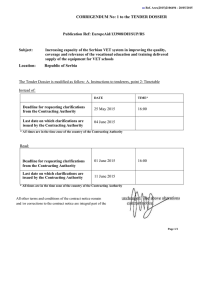

advertisement