1 Chapter 1 THE PROBLEM

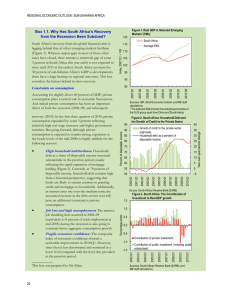

advertisement