Constitution

advertisement

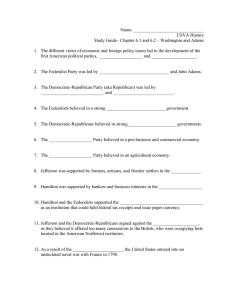

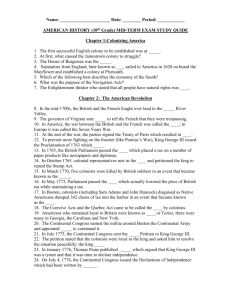

Constitution Soon after the states ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788, America began the process of choosing government officials. Members of the House of Representatives were directly elected by citizens in each state. Each state legislature picked two people to serve in the Senate. Electors of the Electoral College were also selected, and they in turn elected George Washington as president. One of Congress's first acts was to pass the Judiciary Act of 1789 which set the size of the Supreme Court at six justices and created a system of lower federal courts. Washington then named judges to fill these posts. The president then appointed people to head executive departments: Thomas Jefferson was named Secretary of State, and Alexander Hamilton was appointed Secretary of the Treasury. The new government was now in place and ready to begin solving America's difficult problems. Led by Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton, the federal government began correcting the monetary and financial mess left over from the Revolution and Confederation. After heated debate, Congress approved Hamilton's plan for the federal government to pay all U.S. and state loans remaining from the Revolution. Also passed were revenue-raising tariffs as well as excise taxes on products like whiskey. Finally, Congress enacted Hamilton's controversial plan for a U.S. Bank. Another task of the new government was to end the fear of anarchy which had persisted since Shays's Rebellion (1786). An opportunity to demonstrate "law and order" came in 1794 when western Pennsylvania distillers refused to pay the excise tax on whiskey. Determined to crush this Shays-like threat to authority, Washington sent a large army into Pennsylvania and the so-called Whiskey Rebellion was quickly put down. Washington's actions made it clear to all that, unlike government under the Articles of Confederation, government under the U.S. Constitution would enforce the law. Meanwhile Washington sought to avoid clashes with foreign countries which might lead the young U.S. into a war it might lose. Toward this end, Washington issued the Proclamation of Neutrality (1793). This declared that the U.S. would not take sides in the war which was raging between Great Britain and the newly proclaimed Republic of France. While many Americans praised Washington and Hamilton for their strong leadership, not all Americans were happy with their policies. Many opposed the tariffs and, as you have read, the excise tax on whiskey. Some wanted the U.S. to support France in its war with Britain -- after all France had become a republic and had once helped American Patriots win their independence. To add to the controversy, people like Thomas Jefferson argued against Congress's creation of a U.S. Bank. He claimed that Congress had dangerously exceeded its powers because Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution had not specifically authorized Congress to create a bank. But Hamilton argued that since the Constitution specifically authorized Congress to coin money and regulate its value, the Constitution by "implication" also authorized Congress to create a bank. Jefferson protested against this use of "implied powers" and the "elastic clause" claiming it would lead to overly strong and abusive government. To Jefferson's great disappointment, Washington sided with Hamilton. The nation became split over the issue of the U.S. Bank and other policies of the government. Led by Jefferson, those who opposed Hamilton's financial plan created the Democratic-Republican Party. Former Anti-Federalists, who had always feared national government's power might threaten states' rights, joined the Democratic-Republicans. Meanwhile supporters of Hamilton's ideas formed the Federalist Party. The election of 1796 was the first major show-down between the two parties. With the support of Washington, who was retiring after two terms in office, the Federalists defeated the Democratic-Republicans. John Adams, a Federalist and vice-president under Washington, was elected president defeating the Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson. The Federalists also won control of Congress. President Adams faced difficulties during his term in office. Many Americans, especially Democratic-Republicans severely criticized Adams for his domestic and foreign policies. In 1798 the Federalist-controlled Congress passed the Sedition Act. This act outlawed "false, scandalous, and malicious" statements against Congress or the president. The Sedition Act outraged Democratic-Republicans who charged that it was unconstitutional. By the time elections were held in 1800, many Americans had turned away from the Federalists. In that year, the Democratic-Republicans and their presidential candidate, Thomas Jefferson, were elected to power. After their defeat in 1800, the Federalists began to fade and later passed into history. But their contribution to America should not be forgotten. They created a strong national government at a critical time in American history. Having done so, America's survival as an independent republic was virtually assured. Following the election of Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans to power in 1800, many predicted a collapse in the power of the national government. But to the contrary, events pushed America into a period of growing nationalism. Even Democratic-Republicans, who had once been ideologically bound to the idea of states' rights, began to support Federalist-style national policies. The years between 1800 and 1825 became years when national interests seemed, at least on the surface, stronger than sectional differences. Foreign developments helped foster American nationalism and national power. In 1803 Napoleon offered to sell Louisiana, a huge area of land between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains. Despite the lack of specific constitutional authority to buy territory, Jefferson put aside his "strict constructionist" principles and supported the purchase of Louisiana. The action doubled the size of the U.S. and gave Americans a greater feeling of national power. Meanwhile violations of American rights on the high seas, especially by the British, excited nationalist feelings. British seizure of American ships and seamen, as well as the desire to conquer British Canada, caused the U.S. to declare war. Although the war ended in a draw, America's standing up to the British boosted national pride. Nationalist feelings swelled even more when an American "police action" in Spanish Florida led to the sale of that land to the U.S. in 1819. The growing sense of American identity and power helped lead to the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. In it, the U.S. stated that it would oppose further European colonization in the American continents and that the U.S. would continue to isolate itself from European politics. Growing nationalism was also seen in domestic developments. The DemocraticRepublican controlled national government moved to support strong national policies. Democratic-Republicans, who had once been against the U.S. Bank, began to see its importance to the nation as a whole. In 1816 they renewed its charter. Wanting to strengthen the nation's manufacturing sector, Democratic-Republicans reversed, for the time being, their opposition to tariffs and voted for protectionism. Believing that improved transportation was in the national interest, Congress voted money for the construction of east-west roads. Meanwhile the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, delivered decisions which confirmed, if not broadened, the power of the national government. As the Democratic-Republican majority in Congress began to adopt national policies, more people deserted the old nationalist party -- the Federalist Party -- and joined the majority. The Federalist Party soon disappeared. The country seemed, for the time being at least, free from deep political division. This period of national unity, 1817-1824, was called the Era of Good Feelings. Although nationalism seemed strong during the Era of Good Feelings, sectional differences occasionally disrupted the spirit of unity. Many New Englanders opposed the U.S. declaration of war against Britain in 1812. During the course of the war, some New Englanders even spoke of secession from the Union. A growing division between those opposed to slavery and those in favor began to strain the nation. This conflict was seen when Missouri asked to join the Union in 1818. Also, controversy over the tariff, once muted, was beginning to stir again. Future years would see these sectional issues overcome the general feeling of national unity of the early 1800s. Following the election of Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans to power in 1800, many predicted a collapse in the power of the national government. But to the contrary, events pushed America into a period of growing nationalism. Even Democratic-Republicans, who had once been ideologically bound to the idea of states' rights, began to support Federalist-style national policies. The years between 1800 and 1825 became years when national interests seemed, at least on the surface, stronger than sectional differences. Foreign developments helped foster American nationalism and national power. In 1803 Napoleon offered to sell Louisiana, a huge area of land between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains. Despite the lack of specific constitutional authority to buy territory, Jefferson put aside his "strict constructionist" principles and supported the purchase of Louisiana. The action doubled the size of the U.S. and gave Americans a greater feeling of national power. Meanwhile violations of American rights on the high seas, especially by the British, excited nationalist feelings. British seizure of American ships and seamen, as well as the desire to conquer British Canada, caused the U.S. to declare war. Although the war ended in a draw, America's standing up to the British boosted national pride. Nationalist feelings swelled even more when an American "police action" in Spanish Florida led to the sale of that land to the U.S. in 1819. The growing sense of American identity and power helped lead to the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. In it, the U.S. stated that it would oppose further European colonization in the American continents and that the U.S. would continue to isolate itself from European politics. Growing nationalism was also seen in domestic developments. The DemocraticRepublican controlled national government moved to support strong national policies. Democratic-Republicans, who had once been against the U.S. Bank, began to see its importance to the nation as a whole. In 1816 they renewed its charter. Wanting to strengthen the nation's manufacturing sector, Democratic-Republicans reversed, for the time being, their opposition to tariffs and voted for protectionism. Believing that improved transportation was in the national interest, Congress voted money for the construction of east-west roads. Meanwhile the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, delivered decisions which confirmed, if not broadened, the power of the national government. As the Democratic-Republican majority in Congress began to adopt national policies, more people deserted the old nationalist party -- the Federalist Party -- and joined the majority. The Federalist Party soon disappeared. The country seemed, for the time being at least, free from deep political division. This period of national unity, 1817-1824, was called the Era of Good Feelings. Although nationalism seemed strong during the Era of Good Feelings, sectional differences occasionally disrupted the spirit of unity. Many New Englanders opposed the U.S. declaration of war against Britain in 1812. During the course of the war, some New Englanders even spoke of secession from the Union. A growing division between those opposed to slavery and those in favor began to strain the nation. This conflict was seen when Missouri asked to join the Union in 1818. Also, controversy over the tariff, once muted, was beginning to stir again. Future years would see these sectional issues overcome the general feeling of national unity of the early 1800s. During the Era of Good Feelings (1817-1824), a sense of nationalism seemed to unite America. A single political party, the Democratic-Republican Party, had become so broadly appealing that partisan rivalry began to fade. But after the election of 1824, political and sectional conflict began to shatter this unity. The election of 1824 was unusual. With four candidates, seeking the presidency, Andrew Jackson won the most electoral votes but not the majority. So, as directed by the Constitution, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. There, with the support of Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams was elected president. (He later chose Clay to be secretary of state.) Jackson and his many "common folk" supporters charged that a "corrupt bargain" had been made between Adams and Clay. The Democratic-Republican Party began to split apart. Jackson and his followers called their wing of the party the Democratic Party. Meanwhile Adams, Clay, and their followers, many of whom were businessmen from the Northeast, formed the National Republican (Whig) Party. As president (1825-1829), John Quincy Adams urged Congress to pass laws which would encourage manufacturing, build transportation systems, and support education and the arts. He favored protective tariffs and a strong U.S. Bank. But Jackson's followers in Congress criticized the "aristocratic" Adams and refused to support most of his "Hamiltonian" programs. In the election of 1828, Adams's support was generally limited to the Northeast. With support from the "common man" of the West and South, the Democratic candidate, Andrew Jackson, was elected president. After Jackson's election the divisive forces of sectionalism grew stronger. High import-duty increases resulting from the Tariff of 1828 angered Southerners. In 1832, South Carolina passed its Ordinance of Nullification which claimed South Carolina's right to nullify (void) federal tariffs. South Carolina also threatened to secede from the Union if the national government tried to enforce the tariff. Not a person to be bullied, Jackson asked Congress to authorize his use of the army and navy to enforce the law. Anxious to prevent war, a compromise tariff was passed and the threat of secession passed -- for the time being. But Jackson did wage "war" on two other fronts. First, Jackson carried out his promise to "kill the U.S. Bank" and vetoed a bill to recharter it in 1832. Jackson's second "war" was with the Native American Indians. At the urging of Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. According to this law, the U.S. would negotiate treaties with eastern Indians requiring them to leave their traditional homelands and move to new lands west of the Mississippi River. When some Indians resisted, armed conflict such as Black Hawk's War broke out. This and other resistance was put down. While president, Jackson was viewed as a champion of democracy and a hero of the "common man." During his administration, the growing spirit of democracy and equality (among white men) led to the establishment of manhood suffrage (for whites) in new Western states. Eastern states were also caught up in the spirit and began to eliminate property qualifications for voting. New and more democratic methods of choosing presidential candidates were adopted. Jackson's destruction of the Bank of the U.S., which Westerners called the "money monopoly of the aristocrats," was viewed at first as a victory for democracy. But with the decentralization of money controls, state banks once again printed too much money. Soon after Jackson's retirement and the election to the presidency of his vice-president, Martin Van Buren, the financial chaos deepened. Soon the nation was plunged into the worst depression it had known. By the end of Van Buren's first term, many Americans were ready to give the Whig (National Republican Party) candidate, William Henry Harrison, a turn at leading the country.